Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

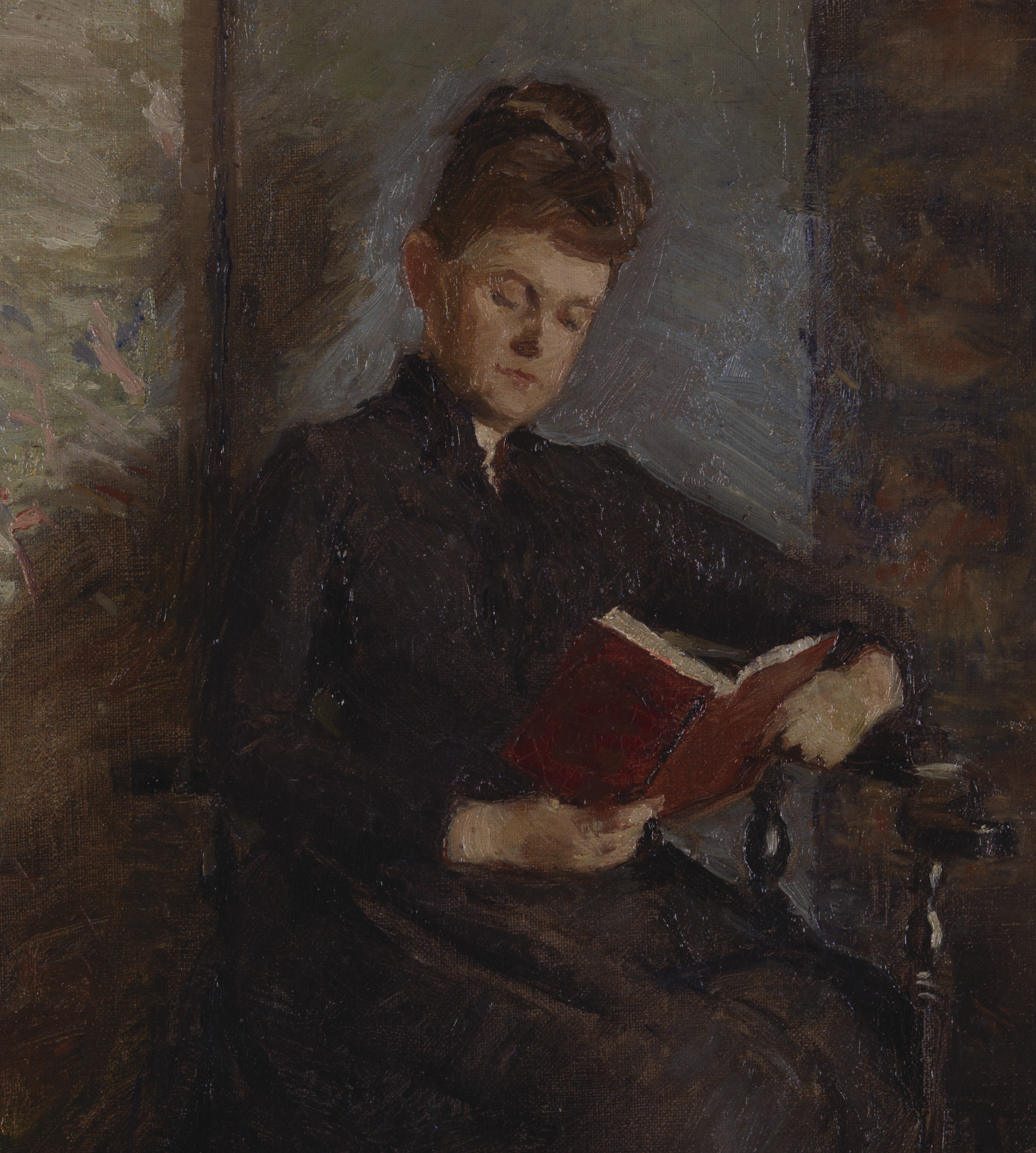

Woman Reading Under a Tree

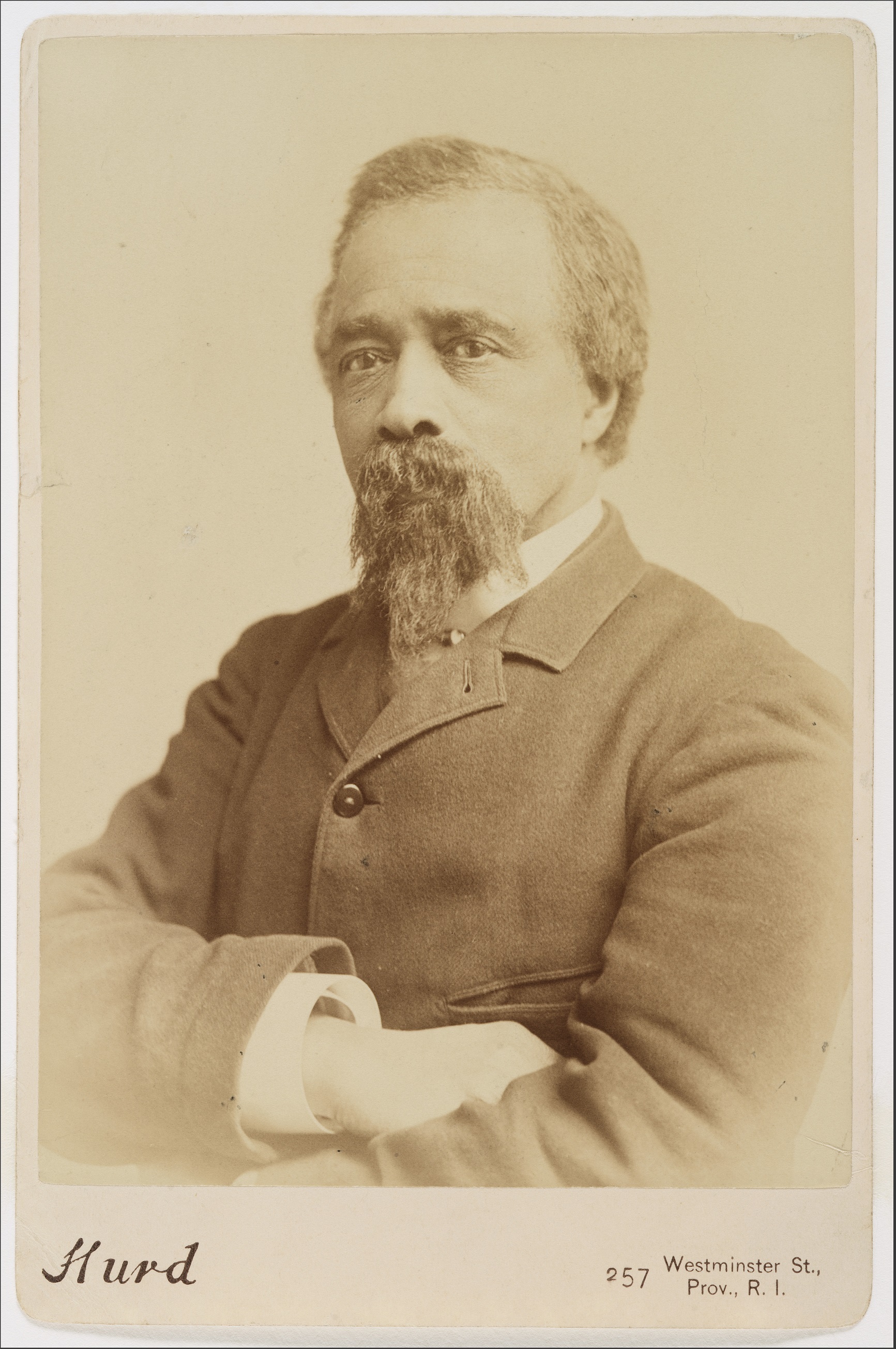

Edward Mitchell Bannister

While living in Boston in the early 1850s, Edward Mitchell Bannister could not have ignored the city’s growing fascination with the Barbizon “School” (style) of painting then being imported from France. In contrast to the meticulous detail and strong coloring employed by such then-fashionable Hudson River Valley and White Mountains landscapists as Thomas Cole and Benjamin Champney, Barbizon artists emphasized cooler and more tonally unified coloring, looser brushwork, and softer forms.

The first Barbizon painting exhibited in Boston (1853) was created by the now-forgotten Frenchman Eugène Cicéri, and the following year Bostonians began admiring the French master Jean-François Millet, whose scenes of peasants in the fields were especially popular. The vogue for Barbizon pictures gained momentum in 1855, when the talented and well-connected artist William Morris Hunt returned to Boston after twelve years in Europe, including a period of study with Millet. Hunt helped an 1858 exhibition of Barbizon paintings at the Boston Athenaeum become a huge success, inspiring both New England collectors and artists as wide-ranging in age and background as Bannister, Longfellow, and Davis—all represented in this gallery. Some New Englanders also perceived in Barbizon paintings a moral element that appealed to them; the collector Thomas Gold Appleton wrote of Millet’s paintings: “They have a Biblical severity and remind us of the gravest of the Italian masters.”

Note Cicéri’s placement of two patches of daylight near the center of his composition—one in the tree canopy and the other on the forest floor—to remind viewers that the weather beyond this darkened woodland was bright. Likewise, in his painting Bannister deftly contrasted light and shadow, even using a patch of blue sky visible through the foliage at top left.

Like Hunt, Bannister included a female figure to provide a sense of scale and to suggest the harmony of nature and humankind. Notice Hunt’s deft orchestration of the vertical tree trunks to create a rhythm across the picture plane—something Bannister also handled masterfully.

Women Reading

In Bannister’s painting, a woman reads while gentle breezes flutter the leaves and grasses around her. This scene evokes the Massachusetts poet-philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Transcendentalist belief in the unity of nature and people. In Nature (1849), he wrote: “In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, — no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair… I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.” Emerson’s readers, possibly including Bannister, no longer saw nature as something to be conquered, but rather something that offered peace, which this woman may well have been experiencing.

Although depicted throughout the history of art, women reading took on an urgent symbolic power in the later nineteenth century as more women demanded, and secured, a higher education. Bannister often took his art students—both men and women—outside Providence to paint and sketch outdoors. The woman seen here may in fact have been one of his students, though the flock of geese grazing at left would have inferred to some viewers that she was instead a farm girl tending them. Compare the tiny detail of the woman reading here with artist Mabel Stuart’s Portrait of Mary Elizabeth Cutting Buckingham in this exhibition’s second gallery. By situating Buckingham indoors and centering the composition on her, the artist made reading the subject of her composition, rather than an incidental occurrence tucked off to one side.

Breaking Barriers

Scholar Rosalyn Delores Elder notes that “in 1853 Bannister became a barber in a Boston salon owned by Christiana Babcock Carteaux (1819–1902), a prosperous entrepreneur whom he later married. Working as a barber put Bannister in the higher echelons of African American society.” Motivated at least in part by his determination to disprove an 1867 article in the New York Herald stating that “the Negro seems to have an appreciation of art” but is “manifestly unable to produce it,” Bannister achieved impressive success as an artist. Elder adds that his wife’s financial success enabled Bannister “to pursue self-guided art studies, the route he had to map out because racism barred him from the traditional path of apprenticeship and travel to Europe. Bannister participated in exhibitions at the Boston Art Club and other venues that afforded him opportunities to associate with others in the art community.” He ultimately became a popular instructor at the Rhode Island School of Design and a co-founder of the Providence Art Club.

Learning to Look

Most of us first look at a painting and see the overall image. We imagine being in the place where the artist was. Has the artist captured the mood of a rainy day in the city? What was the person in this portrait like? But we can also learn something by looking more closely at what’s on the canvas. How has the way the artist applied the paint enhanced the image? How does the composition direct your eye around the scene? How do the choices this artist made relate to those made by another artist?

Several areas of Edward Mitchell Bannister’s Woman Reading Under a Tree merit closer looking. Click the hot spots in the image for more details.

The arching branch at center right guides our eye toward the massive central tree trunk in the distance and complements the verticality of the adjacent trunks.

The patch of blue sky visible through the foliage at top left offers us a sense of perspective and a reminder of how clear the weather is.

Bannister masterfully contrasted brilliant sunlight on the grass with shadows in the foreground.

to learn more

Paintings from the Eustis Estate

ComparisonsBannister’s capacity to find luminosity and poetry in seemingly ordinary scenery was sustained by the younger artist Laura Coombs Hills (1859–1952). Hanging in the parlor on the ground floor of the Eustis Estate is The Shaded Stream, which she painted in her hometown of Newburyport, Massachusetts. Although Hills became better known for her pastels and miniatures, she excelled at Barbizon-inspired landscapes like this, made around the same time Bannister created his.

Right: Laura Coombs Hills (1859–1952), The Shaded Stream, c. 1880, oil on canvas, 24 x 28 x 3 ¼ in., Museum Purchase, 2016.56.1.

Learn more about The Shaded Stream below.

The Shaded Stream

In the late nineteenth century Laura Coombs Hills (1859–1952) became one of a small number of women who were able to earn their livings as artists. Born in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and trained in Boston and New York, Hills is best known for pastels and miniatures. However, she also painted a few Barbizon-inspired landscapes probably in the 1880s. This painting is one of them, focusing not on the monumental landscapes that captivated earlier artists but instead on the quotidian or commonplace. Hills has come to be known as an important member of The Boston School, along with Frank Weston Benson (his painting Four Children at North Haven also hangs in the parlor) and Edmund Tarbell whose painting Breakfast on the Piazza is on display in the dining room.