Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

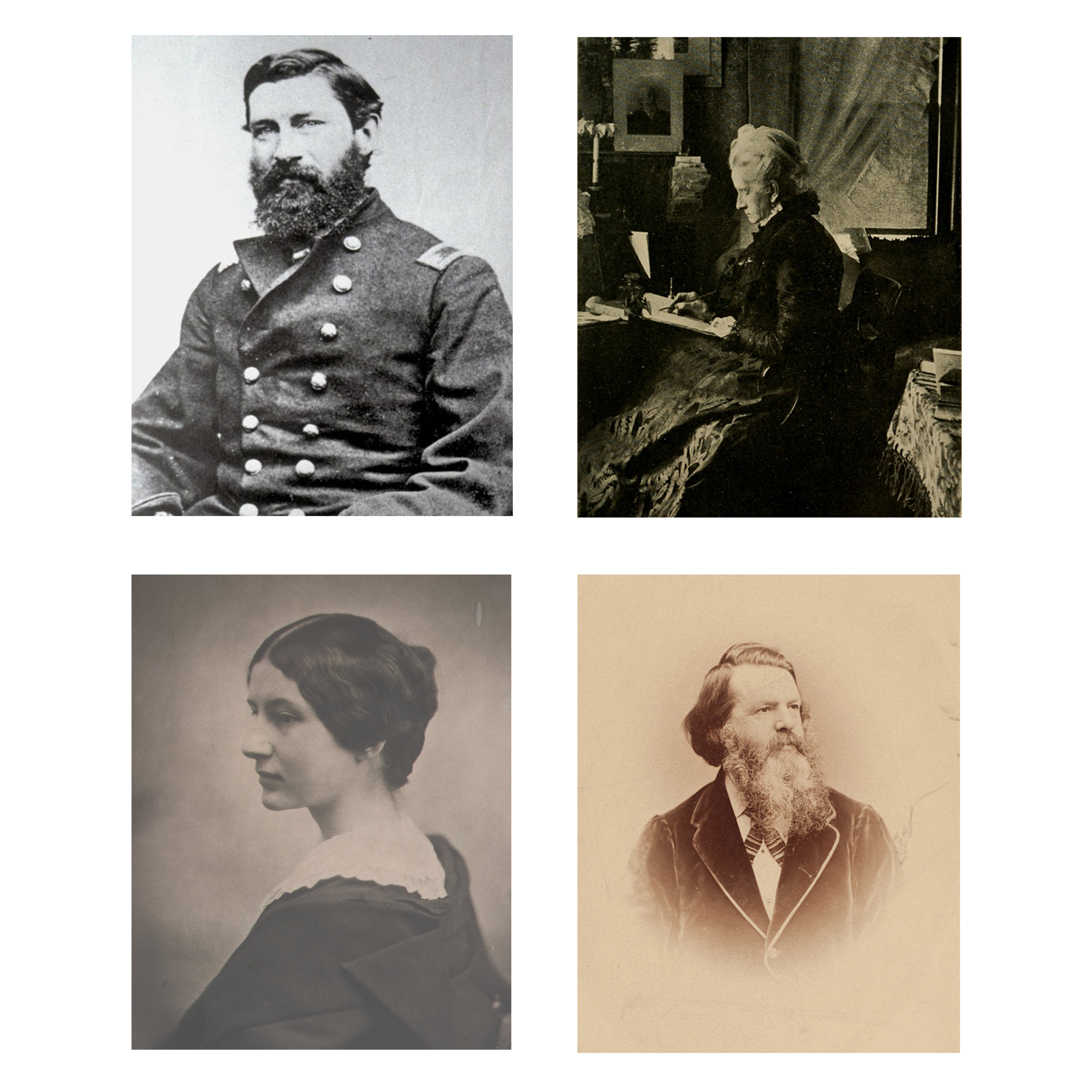

Replica of the Self-Portrait of Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Elizabeth Adams

Paintings conservator Lisa Mehlin and curator Nancy Carlisle discuss good news about preserving the painting and its attribution.

A Curator’s Discovery

As mentioned in the video above, Artful Stories co-curator Nancy Carlisle made an exciting discovery in the course of her exhibition research that cast new light on a painting in Historic New England’s collection. Here is the story in her words:

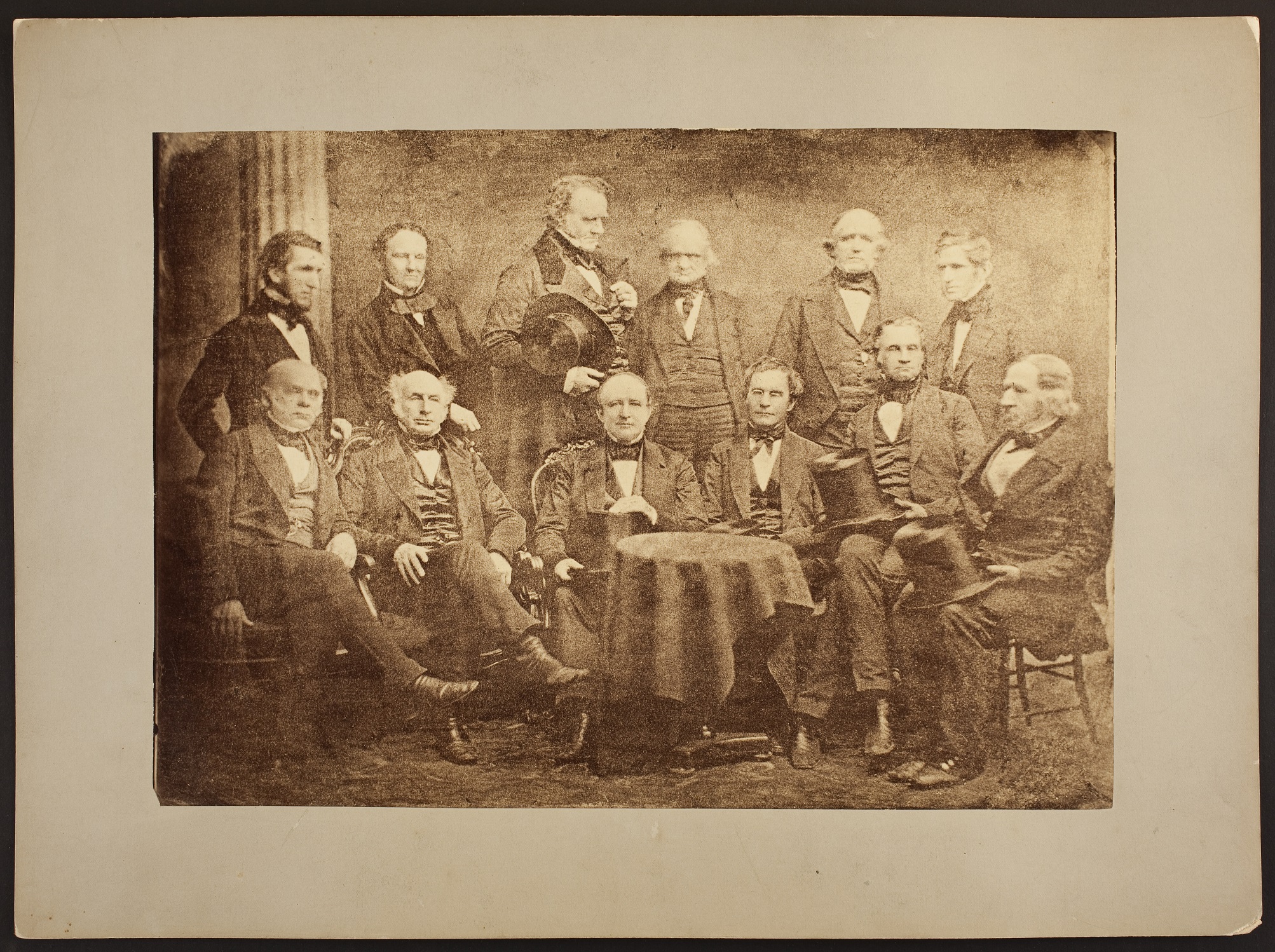

“When I first looked into who Elizabeth Adams was I went to Who Was Who in American Art (Peter Falk, editor). There I learned that an Elizabeth Adams, born in Boston, had exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1885. Interesting. But not exactly enough to hang your hat on. The clue was in the donor, Boylston Adams Beal (1856–1940), who was the nephew of Annie Adams Fields. Annie Fields was a writer at the center of nineteenth-century Boston’s literary community and a noted diarist. From Annie’s diaries we learn that her sister Elizabeth – Lizzy – joined Annie and her husband James T. Fields on their honeymoon trip to Europe in 1859. After their return Lizzy stayed behind, remaining in Europe for eleven years, studying art in Paris and Florence. The rest of Lizzy’s story unfurled when we discovered a privately printed memorial tribute in the collections of the Boston Athenaeum.”

Lizzy Adams and Her Notable Family

Elizabeth (“Lizzy”) Adams grew up in a family that was highly accomplished and long established in Massachusetts. On her father’s side she was related to—among others—the U.S. Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, and on her mother’s side to the writer Louisa May Alcott. Her father was the physician Zabdiel Boylston Adams, M.D., whom her younger brother, Zabdiel Boylston Adams, Jr., M.D., followed into the medical profession.

Elizabeth’s older sister, Sarah May Holland Adams, contracted polio as a youngster and later spent twenty-two years as companion to her widowed mother, after whom she was named. Following her mother’s death, Sarah spent fifteen years in Germany, where she became an award-winning translator of German literature into English. Their other sister Ann (“Annie”), who was nine years younger than Lizzy, married the publisher, editor, and poet James T. Fields, seventeen years her senior in 1854. (After her husband’s death in 1881, Annie, who was herself a writer, became the life partner of the author Sarah Jewett Orne who features in the fourth gallery through a painting made by Sarah Wyman Whitman. )

It was in 1860 that the trio—James aged 43, Lizzy 34, and Annie 26—departed for the long tour of Europe that brought Lizzy face-to-face with both serious art instruction and masterworks of fine art.

While living in Florence, Lizzy Adams surely spent time in the Uffizi Gallery, renowned for its collection of masterworks by such talents as Botticelli and Raphael. By this time, the Vasari Corridor, a once-private passageway that runs from the Uffizi Gallery to the Pitti Palace, crossing the River Arno above the famous Ponte Vecchio, was lined with self-portraits invited from important artists from across the Western world. One of the few there made by a woman came from Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842), whose skill and prestige were surely admired by Lizzy Adams.

After her return to the U.S., Lizzy and her distant cousin, Frances Burnap, set up a home and studio in Baltimore where Lizzy taught classes and continued to paint, primarily portraits. That home and their summer property in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, were, according to Adams’s biographer Richard Burton, places where like-minded friends gathered for lively conversations about art and literature. Burton notes that the couple traveled abroad regularly, something to which Lizzy had grown accustomed during her years in Europe.

From the Conservator's Notebook

Craquelure and Cleaning

Historic New England objects conservator Michaela Neiro supervised the conservation treatment and stabilization of this exhibition’s paintings and frames over a period of two years. The Conservator’s Notebook features explanations and insights that Michaela has drawn from her project notebook, including close-up photographs showing how the work was done.

Craquelure, especially visible on either side of the figure’s face in the photograph on the left, refers to the pattern of cracking seen on the surface of a painting. It is predominantly caused either by the uneven drying of the artist’s materials (the canvas, the ground, the paint medium and the varnish) or the ageing and environment of the finished painting. Sometimes craquelure is in a very distinctive pattern: radiating from the edges, bullseye on the surface, or it can be very random as in this case, with non-directional cracks that have no relationship to the canvas weave, the stretcher or something that hit the surface. In general, the layers of materials that make up a painting become more brittle over time and have more negative reactions to swings in relative humidity and temperature.

The chemistry and physics of craquelure are very complex, but the end result is generally the same: the painted surface is very delicate, the paint is lifting from the canvas at the edges of each crack. Depending on the severity of the problem, some craquelure can be addressed from the front of the painting – a conservator wicks adhesive into the cracks with a tiny brush and secures the lifting cracks one by one with a small tacking iron or weights. In this case, since the craquelure was so widespread, advanced, and disfiguring, the painting had to be lined with an additional fabric using a heated suction table. This secures the lifting paint edges and flattens the surface overall, creating a more stable and more visually pleasing painting.

You can see how removing the yellowed varnish transformed the appearance of the painting.

In the time lapse video below, paintings conservator Lisa Mehlin cleans the Adams painting in her studio.