Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

Richard Norton

Antonio Mancini

The intensity and diversity of Antonio Mancini’s techniques stemmed not only from his innate genius and awareness of modernist practices emerging across Europe, but also, at least in part, from his ongoing struggle with a psychotic disorder, which led to his stay in a Neapolitan asylum in 1881–82. Until late in his life, Mancini was often destitute and relied upon his friends and patrons to survive. His experiments with unorthodox processes included the perspective grid described elsewhere in this section and also the dipping of his fingers into paint to quickly adorn blank dinner plates, which he would give to restauranteurs in exchange for meals.

Unconventional as Mancini’s technique and personality were, Richard Norton probably had many reasons to commission the Italian artist to paint his portrait. The revered American painter John Singer Sargent had long admired Mancini’s talent and encouraged other Bostonians to hire him. Norton probably had seen the earlier portrait of John Lowell “Jack” Gardner, which his renowned collector wife, Isabella Stewart Gardner, had commissioned Mancini to paint in Venice at Sargent’s suggestion. The two portraits are approximately the same size, but Norton’s – made a decade later – is more adventurous: he is surrounded by lush flowers (including a corsage pinned to his lapel) and by a classical marble head signifying his expertise in ancient art. Both men hold a walking stick (then a hallmark of gentility), yet Norton’s spiffy white suit and cream-colored tie, crossed legs, and direct gaze at the viewer telegraph a sense of cosmopolitan ease not present in Gardner’s stiff pose and aloof three-quarter profile.

Mancini In the Studio

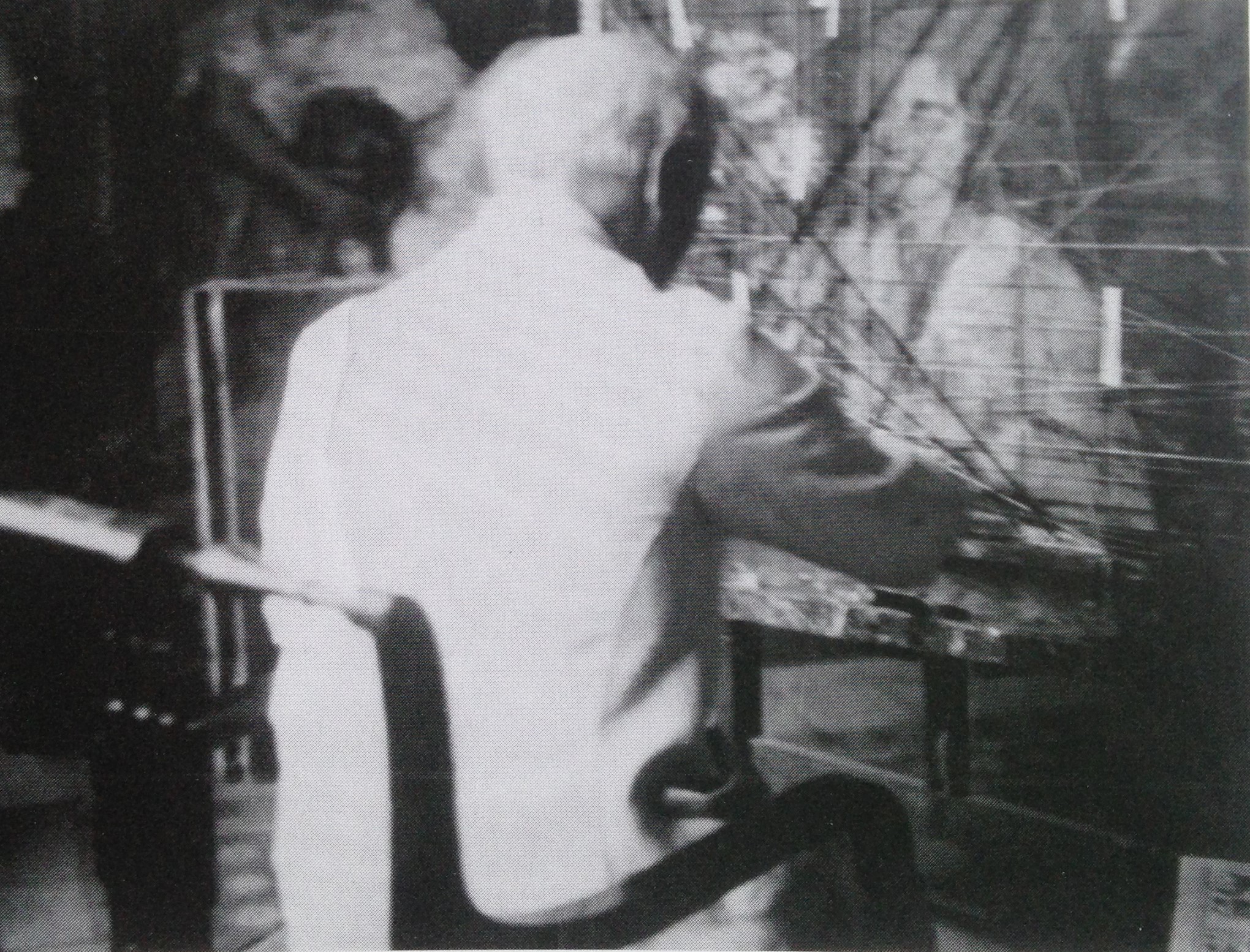

Richard Norton may also have received encouragement to commission Antonio Mancini from his friend Thomas Waldo Story (1854–1915), the well-connected Anglo-American sculptor whose Roman studio was located next door to Norton’s American School of Classical Studies. (Story’s Harvard-educated father had once practiced law in Boston, but eventually moved to Rome to become a successful sculptor.) It is almost certainly T.W. Story’s large studio that is the setting for this photograph showing Mancini sitting with Norton during a break in the portrait’s creation. At the back of this space we see Mancini (wearing a hat); Richard Norton (identifiable by his corsage) sits to his left while an unidentified man stands between them.

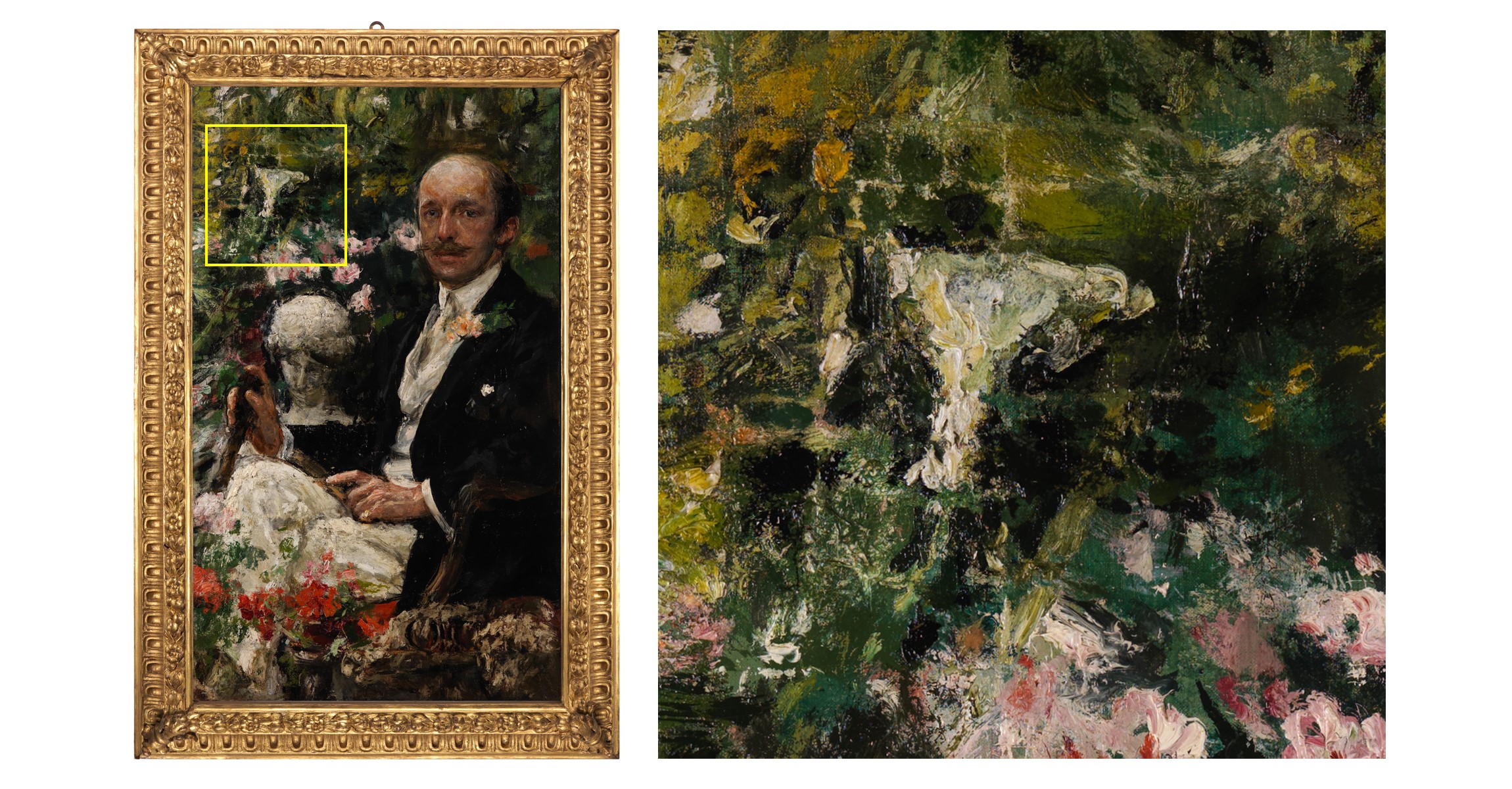

This photograph is particularly interesting because it helps explain a distinctive area of the Norton portrait’s surface. Although paint was applied thickly across much of the canvas, the upper left corner (especially around the white lily) is noteworthy. By zooming in on the lily, we can see the square impressions made by Mancini’s graticola, a perspective grid he used regularly.

This method involved two identical wooden frames, each strung with strings stretched both vertically and horizontally across their middles in order to create a grillwork of squares. One frame was placed against the canvas, and the second between the artist and sitter, providing a screen through which Mancini could look. Focusing on one square at a time, the artist would then paint an abstracted arrangement of its shapes, colors, values, and edges onto his canvas. As we see in the painting’s upper left corner, Mancini often allowed the string marks to show, either subtly or aggressively, imparting a textured, almost quilted decorative quality to the surface. (Look for the rectangular shapes directly above the lily.)

In the photograph of the studio, we can see one of Mancini’s rectangular perspective grids leaning against the wall by the doorway at right. Another photograph from much later in Mancini’s career shows him from behind, offering us a clearer view of how the strings were stretched across the wooden structure.

The thickness and expressivity of Antonio Mancini’s brushwork in the portrait of Richard Norton become more apparent when we contrast them with the relative smoothness of the English artist’s Edward Burne-Jones’s portrait of Richard’s sister, Sara, also in this gallery.

The thickness of the paint also creates some interesting challenges for conservation as you can see in the section below.

From the Conservator's Notebook

Historic New England objects conservator Michaela Neiro supervised the conservation treatment and stabilization of this exhibition’s paintings and frames over a period of two years. The Conservator’s Notebook features explanations and insights that Michaela has drawn from her project notebook, including close-up photographs showing how the work was done.