Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

In the Studio

Most of the exhibition’s paintings were created by artists working in a studio, and some outdoors or in a museum gallery. Several of them offer rare insights into what the artist’s workspace looked like, either through the image itself or through related materials that have come down to us intact.

Longfellow's House and Studio

Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow posed for a series of professional portrait photographs taken in his custom-built studio at Coolidge Point, Manchester, Massachusetts. Notice the diversity of subject matter that he painted, including landscapes, portraits, figures, and narrative scenes. Like many of his colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic, Longfellow used such photographs to foster his reputation as a gentleman-artist. For example, he is seen here holding a palette and brush while wearing a spotless suit in which he surely had never painted. Earlier generations of New Englanders had often perceived artists as uncouth, decadent, or unproductive. Here, by contrast, Longfellow’s personal elegance and prolific output are very much in evidence.

Itinerant Artist Scene

Unknown artist

Northeastern United States, c. 1845

Colored pencil and water-based media on paper

15 1/8 x 18 ¾ in.

Museum purchase

2019.5.1

Oliver Wendell Holmes described itinerant artists as “wandering Thugs of Art whose murderous doings with the brush used frequently to involve whole families; who passed from one country tavern to another, eating and painting their way.” He despised the work that still “too frequently” ornamented the walls of taverns and homes. But in the days before photography was widely available, traveling artists offered an affordable and accessible alternative to their academy-trained colleagues. This charming scene full of comical detail shows a family gathered in their kitchen while just such a “thug” begins to paint the eldest son.

Gertrude Fiske's Studio

In this video the artist’s great-niece describes what it feels like to visit Gertrude Fiske’s studio, still intact more than fifty years after the artist’s death on her family’s property outside of Boston.

Video courtesy of the Portsmouth Historical Society. Produced by Steve Sanger of oneminutebrands in conjunction with Gertrude Fiske: American Master, a major exhibition that was held at the Portsmouth Historical Society in 2018.

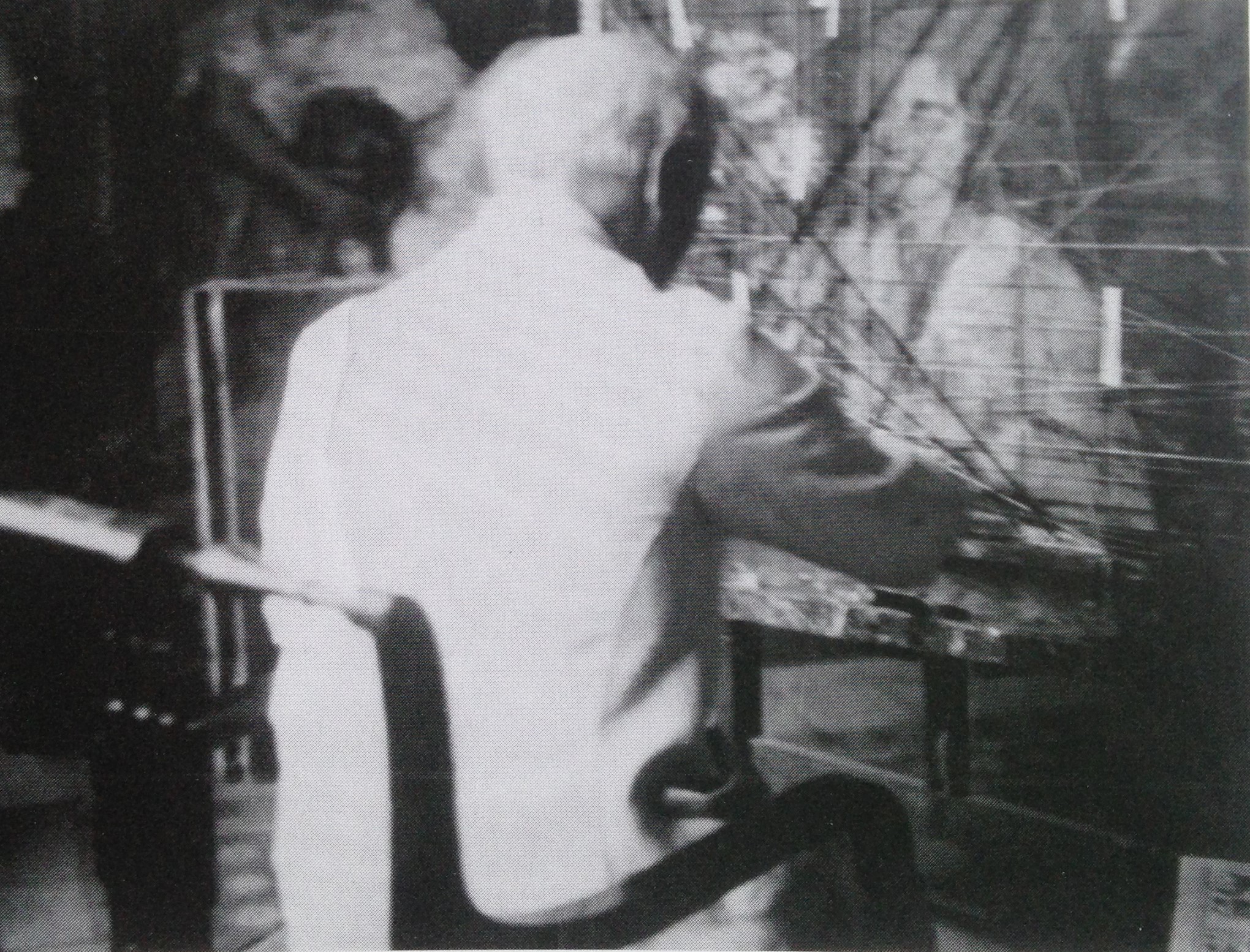

Mancini In the Studio

Richard Norton may also have received encouragement to commission Antonio Mancini from his friend Thomas Waldo Story (1854–1915), the well-connected Anglo-American sculptor whose Roman studio was located next door to Norton’s American School of Classical Studies. (Story’s Harvard-educated father had once practiced law in Boston, but eventually moved to Rome to become a successful sculptor.) It is almost certainly T.W. Story’s large studio that is the setting for this photograph showing Mancini sitting with Norton during a break in the portrait’s creation. At the back of this space we see Mancini (wearing a hat); Richard Norton (identifiable by his corsage) sits to his left while an unidentified man stands between them.

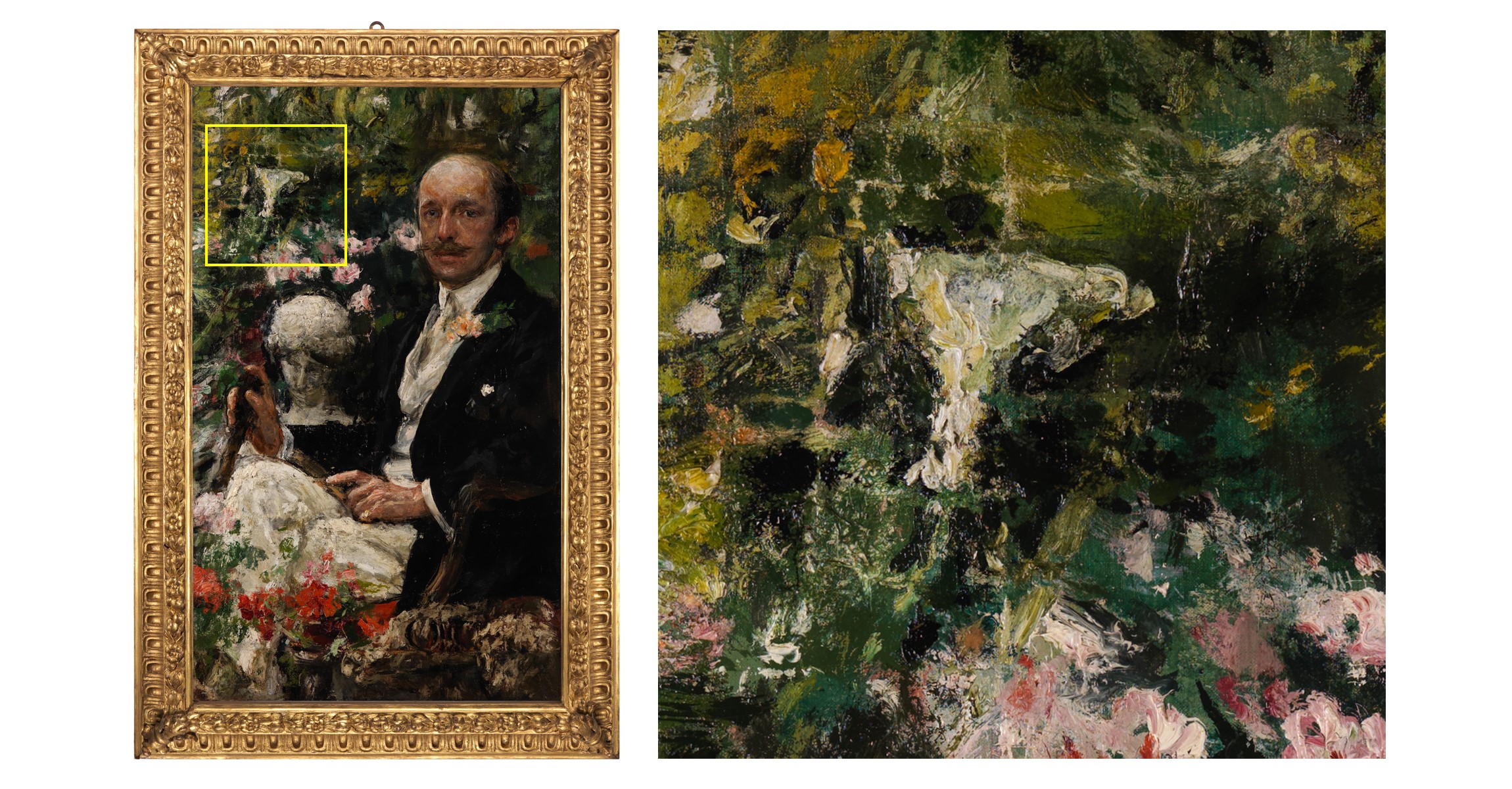

This photograph is particularly interesting because it helps explain a distinctive area of the Norton portrait’s surface. Although paint was applied thickly across much of the canvas, the upper left corner (especially around the white lily) is noteworthy. By zooming in on the lily, we can see the square impressions made by Mancini’s graticola, a perspective grid he used regularly.

This method involved two identical wooden frames, each strung with strings stretched both vertically and horizontally across their middles in order to create a grillwork of squares. One frame was placed against the canvas, and the second between the artist and sitter, providing a screen through which Mancini could look. Focusing on one square at a time, the artist would then paint an abstracted arrangement of its shapes, colors, values, and edges onto his canvas. As we see in the painting’s upper left corner, Mancini often allowed the string marks to show, either subtly or aggressively, imparting a textured, almost quilted decorative quality to the surface. (Look for the rectangular shapes directly above the lily.)

In the photograph of the studio, we can see one of Mancini’s rectangular perspective grids leaning against the wall by the doorway at right. Another photograph from much later in Mancini’s career shows him from behind, offering us a clearer view of how the strings were stretched across the wooden structure.

The thickness and expressivity of Antonio Mancini’s brushwork in the portrait of Richard Norton become more apparent when we contrast them with the relative smoothness of the English artist’s Edward Burne-Jones’s portrait of Richard’s sister, Sara, also in this gallery.

The thickness of the paint also creates some interesting challenges for conservation as you can see in the section below.