Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

William Ralph Emerson Architectural Database > Architectural Career

W. Ralph Emerson: The Architect

Mr. Emerson was a native product of New England, delighting in ingenious contrivances and original inventions, filled with enthusiasm for whatever was spontaneous and natural, and abhorring conventions of every sort. He was the creator of the shingle country house of the New England coast, and taught his generation how to use local materials without apology, but rather with pride in their rough and homespun character… To his friends and pupils he was a source of inspiration, a unique personality, not shaped in the schools, [and] a lover of artistic freedom.

Resolutions on the Death of William Ralph Emerson

Boston Society of Architects, January 18, 1918

Lasting more than fifty years, W. Ralph Emerson’s career transcended architectural styles and boundaries, allowing him to experiment and develop professionally as American architecture evolved over the second half of the 19th century. Emerson entered the field of architecture around 1854, when he joined the office of Jonathan Preston. With training as a mason and having worked as a contractor, Preston understood the construction process and was, by the 1850s, a prominent real estate developer and architect in Boston. Little is known of Emerson’s early years working in Preston’s office, but he likely served as a draftsman and, in the process, learned the profession of architecture. Adept and skilled at his work, Emerson joined Preston’s office, and the two men became business partners on January 1, 1857.

Dating from 1855, Emerson’s earliest identified architectural commission was likely executed under Preston’s watchful eye. In the design of a house for his stepbrother, John Adams Lord, Emerson demonstrated his talents as a delineator and his awareness of popular styles. With a large central tower, ornamented window surrounds, and eaves supported by large brackets, Lord’s Italianate house evoked the villas of Italy despite its wooden construction and location in Kennebunk, Maine.

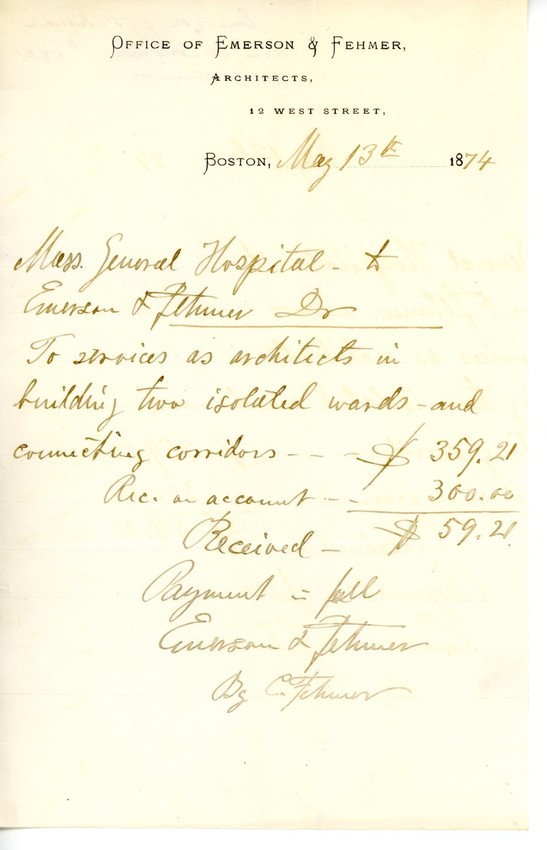

In 1861 the firm of Preston & Emerson dissolved. Though little is known of this period, Emerson appears to have found work as a government architect overseeing construction, alterations, and repair projects, and likely also practiced on his own. Partnering with architect Carl Fehmer in 1867, the firm of Emerson & Fehmer lasted until November 1873.

Born in Germany, Carl Fehmer came to Boston in the early 1850s and worked in several different firms before joining with W. Ralph Emerson. The city’s growth provided many opportunities, and Emerson & Fehmer designed new residential buildings in the Back Bay, additions for the Massachusetts General Hospital, schools, country houses, and – especially after the Great Fire of 1872 – large commercial buildings as well. Many of these designs followed the Second Empire and Stick Styles, but American architectural tastes evolved over the course of the 1870s, and following the dissolution of Emerson & Fehmer, W. Ralph Emerson actively experimented with other architectural styles.

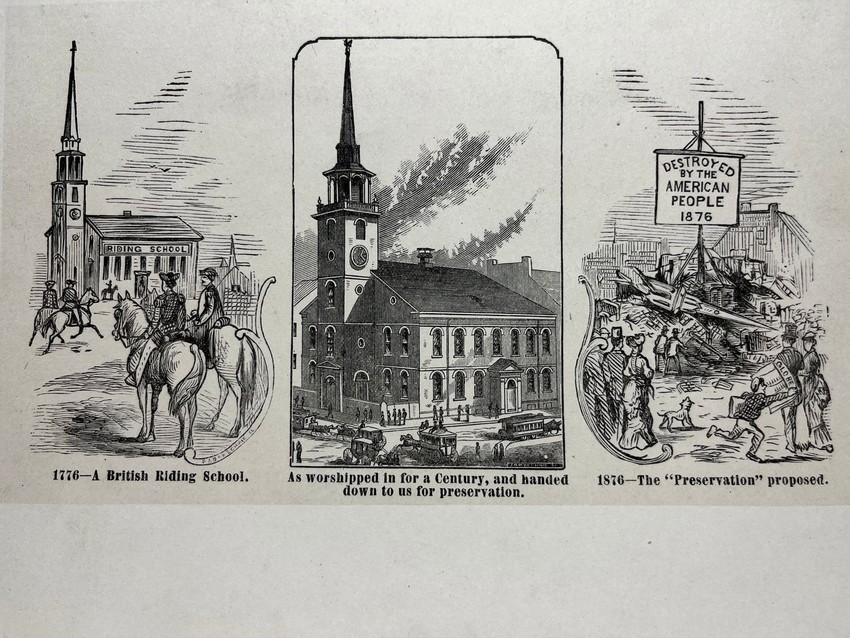

Despite his involvement in new construction, W. Ralph Emerson took great interest in the buildings of early America. In 1869, before members of the Boston Society of Architects, Emerson gave what he described as a “sermon” against the destruction of historic New England houses. He encouraged colleagues and clients to appreciate older buildings, and as an architect he worked to modernize, but preserve, the Old Ship Meeting House in Hingham, Massachusetts. In Boston he was involved in the efforts to save the Old South Meeting House from destruction, and he later oversaw a restoration of the interior.

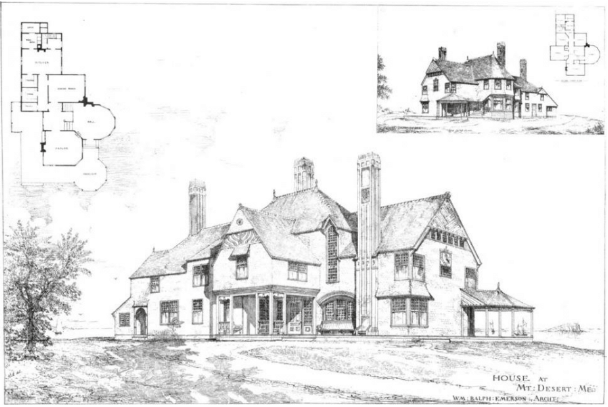

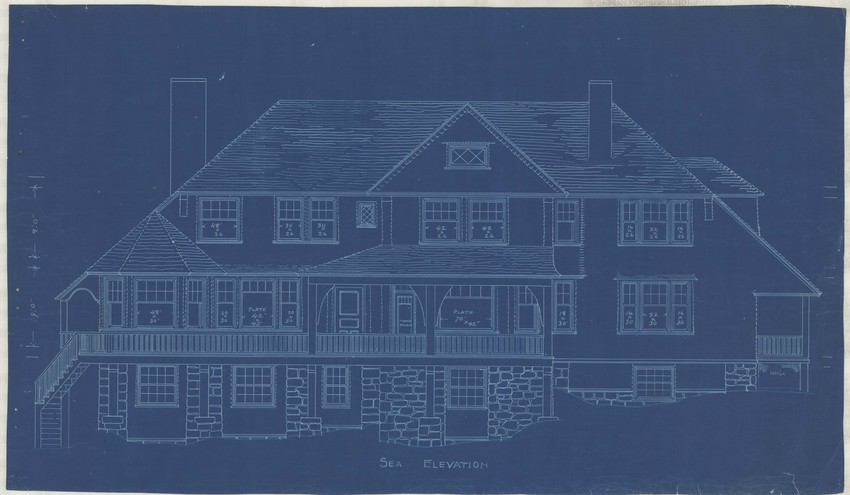

Adapting elements from England’s Queen Anne Style, and combining them with his interest in the architecture of America’s late 18th and early 19th centuries, Emerson was central to the development of what has since become known as the Shingle Style. Defining this architectural style in the 1950s, Vincent Scully cited Emerson’s design for Cyrus J. Morrill at Bar Harbor as an early example. Shingles covering the walls and roof unified the building’s exterior surfaces and its interior spaces; opening the exterior into the interior responded to the needs of modern Americans. Using wooden shingles and emulating architectural details found on many older New England houses, Emerson’s designs were seen as distinct but related to the buildings of early America.

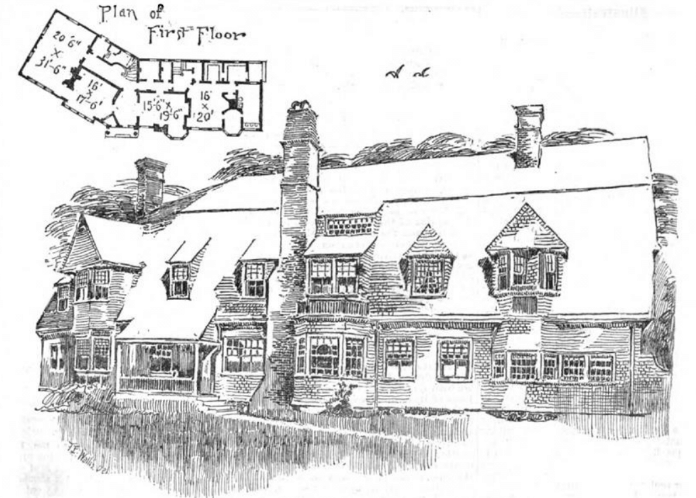

Emerson’s professional reputation became closely associated with shingled country houses, and as growing numbers of wealthy Americans erected summer homes in coastal and mountain locations, his skills as an architect became highly desired. Of nearly 500 identified Emerson designs, more than 20% were designed for seasonal use. Houses like that for Alexander Cochrane in Pride’s Crossing, Massachusetts were carefully conceived to afford elite families with comfortable summer living. Expansive grounds provided places to play tennis, picnic, swim, or fish. The interior arrangement included larger rooms for entertaining, as well as spaces for more intimate gatherings. Despite being a new and modern house, Emerson’s design for Cochrane drew from traditional American forms. Fireplace surrounds emulated 18th century furniture, and windows – filled with small panes of glass – consciously evoked older houses.

Many of Emerson’s country houses were intended to respond to their surroundings, with wooden shingles and granite foundations providing material connections with the New England landscape. Recognized for his abilities, he was hired by prominent individuals including the family of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted to design their Maine summer cottage. Completed in 1896, Felsted’s dramatic rooflines, simple forms, and materials were reminiscent of early American houses and responded to local conditions, while its siting provided the Olmsted family with dramatic views of the surrounding landscape.

In some cases Emerson overtly emulated the houses of early America, creating stoic Colonial Revival designs like that for Charles Wentworth in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Adapting traditional forms, Emerson enlivened the façade of the Wentworth House with a door inspired by Colonial examples and a gently swelling second-story that sheltered the entrance.

By the end of the nineteenth century architectural tastes were changing. Emerson’s design tendencies became less popular as American audiences grew increasingly interested in more formal and heavily ornamented buildings, often drawn from European examples. Writing for The Architectural Review in 1899, Emerson railed against the exuberant use of ornament in new buildings, citing several Boston examples. Calling attention to the recently erected Westminster Chambers, overlooking Copley Square, Emerson criticized claims “that sculpture to the cost of so many thousand dollars was to enrich (?) it. This argument, in a more intelligent order of things, should have doomed it at once.” Having worked as an architect for nearly fifty years, Emerson encouraged his colleagues to reconsider their decisions: “There appears to be a charm in the superfluous that the modern architect cannot resist. He knows it is wrong and in his heart he loves the honest simplicity of a plain building better. Let him then follow his instincts… To him his work will be a pleasure and to the profession a blessing.”

Though he maintained an office in Boston, Emerson’s architectural output declined after 1900. Following the death of his son in 1899, W. Ralph Emerson appears to have devoted more time to his art, and in 1908 he retired from professional practice. With a long and productive career, and having trained and inspired many younger architects, William Ralph Emerson retired to a quintessentially Emersonian house: the one he designed in 1886 for his own occupancy in Milton.