Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

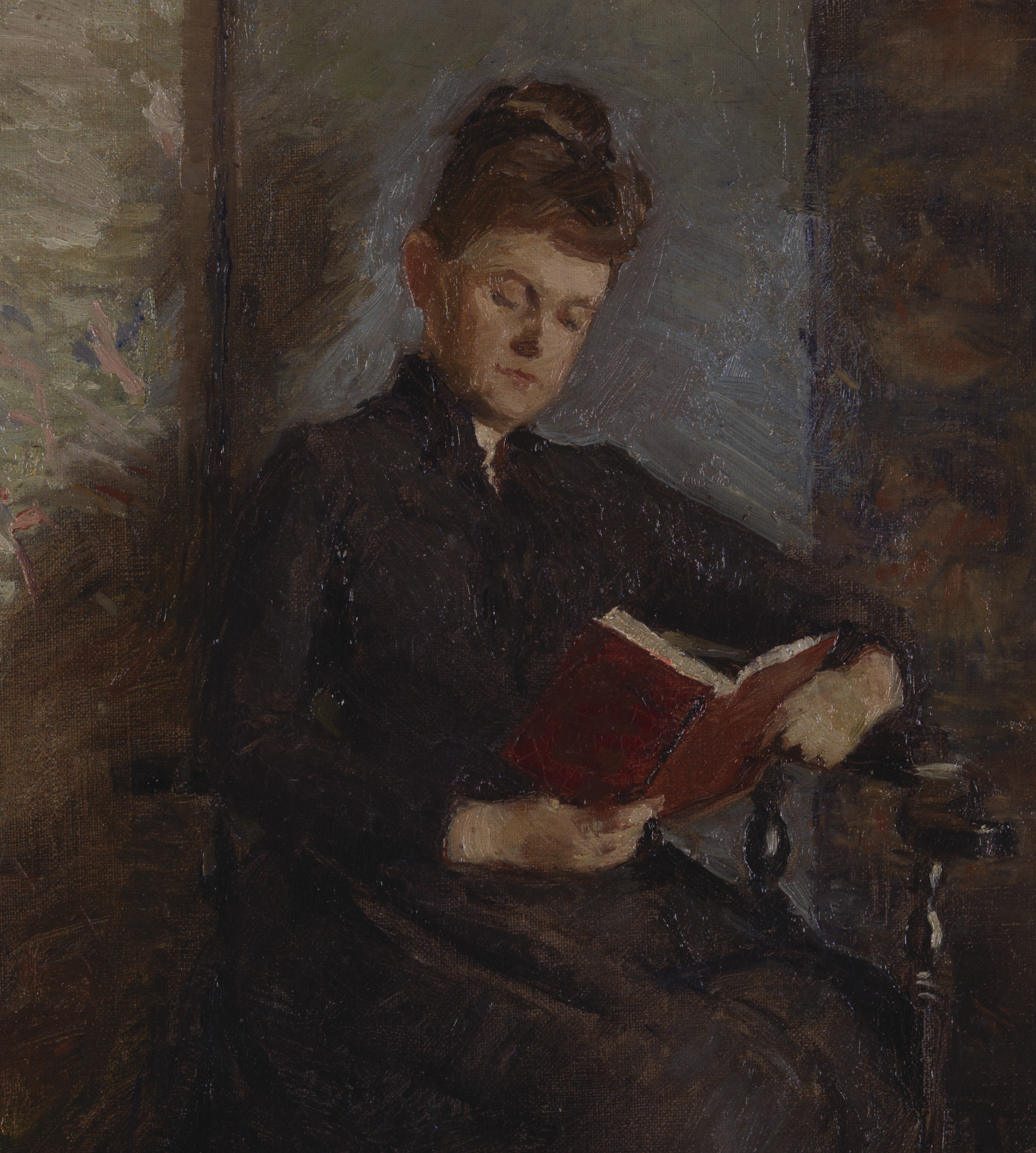

Bannister – woman reading

While living in Boston in the early 1850s, Edward Mitchell Bannister could not have ignored the city’s growing fascination with the Barbizon “School” (style) of painting then being imported from France. In contrast to the meticulous detail and strong coloring employed by such then-fashionable Hudson River Valley and White Mountains landscapists as Thomas Cole and Benjamin Champney, Barbizon artists emphasized cooler and more tonally unified coloring, looser brushwork, and softer forms.

The first Barbizon painting exhibited in Boston (1853) was created by the now-forgotten Frenchman Eugène Cicéri, and the following year Bostonians began admiring the French master Jean-François Millet, whose scenes of peasants in the fields were especially popular. The vogue for Barbizon pictures gained momentum in 1855, when the talented and well-connected artist William Morris Hunt returned to Boston after twelve years in Europe, including a period of study with Millet. Hunt helped an 1858 exhibition of Barbizon paintings at the Boston Athenaeum become a huge success, inspiring both New England collectors and artists as wide-ranging in age and background as Bannister, Longfellow, and Davis—all represented in this gallery. Some New Englanders also perceived in Barbizon paintings a moral element that appealed to them; the collector Thomas Gold Appleton wrote of Millet’s paintings: “They have a Biblical severity and remind us of the gravest of the Italian masters.”

Note Cicéri’s placement of two patches of daylight near the center of his composition—one in the tree canopy and the other on the forest floor—to remind viewers that the weather beyond this darkened woodland was bright. Likewise, in his painting Bannister deftly contrasted light and shadow, even using a patch of blue sky visible through the foliage at top left.

Like Hunt, Bannister included a female figure to provide a sense of scale and to suggest the harmony of nature and humankind. Notice Hunt’s deft orchestration of the vertical tree trunks to create a rhythm across the picture plane—something Bannister also handled masterfully.

Women Reading

In Bannister’s painting, a woman reads while gentle breezes flutter the leaves and grasses around her. This scene evokes the Massachusetts poet-philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Transcendentalist belief in the unity of nature and people. In Nature (1849), he wrote: “In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, — no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair… I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.” Emerson’s readers, possibly including Bannister, no longer saw nature as something to be conquered, but rather something that offered peace, which this woman may well have been experiencing.

Although depicted throughout the history of art, women reading took on an urgent symbolic power in the later nineteenth century as more women demanded, and secured, a higher education. Bannister often took his art students—both men and women—outside Providence to paint and sketch outdoors. The woman seen here may in fact have been one of his students, though the flock of geese grazing at left would have inferred to some viewers that she was instead a farm girl tending them. Compare the tiny detail of the woman reading here with artist Mabel Stuart’s Portrait of Mary Elizabeth Cutting Buckingham in this exhibition’s second gallery. By situating Buckingham indoors and centering the composition on her, the artist made reading the subject of her composition, rather than an incidental occurrence tucked off to one side.