Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

The Conservator's Notebook

Historic New England objects conservator Michaela Neiro supervised the conservation treatment and stabilization of this exhibition’s paintings and frames over a period of two years. The Conservator’s Notebook features explanations and insights that Michaela has drawn from her project notebook, including close-up photographs showing how the work was done.

Richard Norton

Antonio Mancini

This painting’s thick impasto paint required special attention from the conservators.

Copy of the Self-portrait of Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Elizabeth Adams

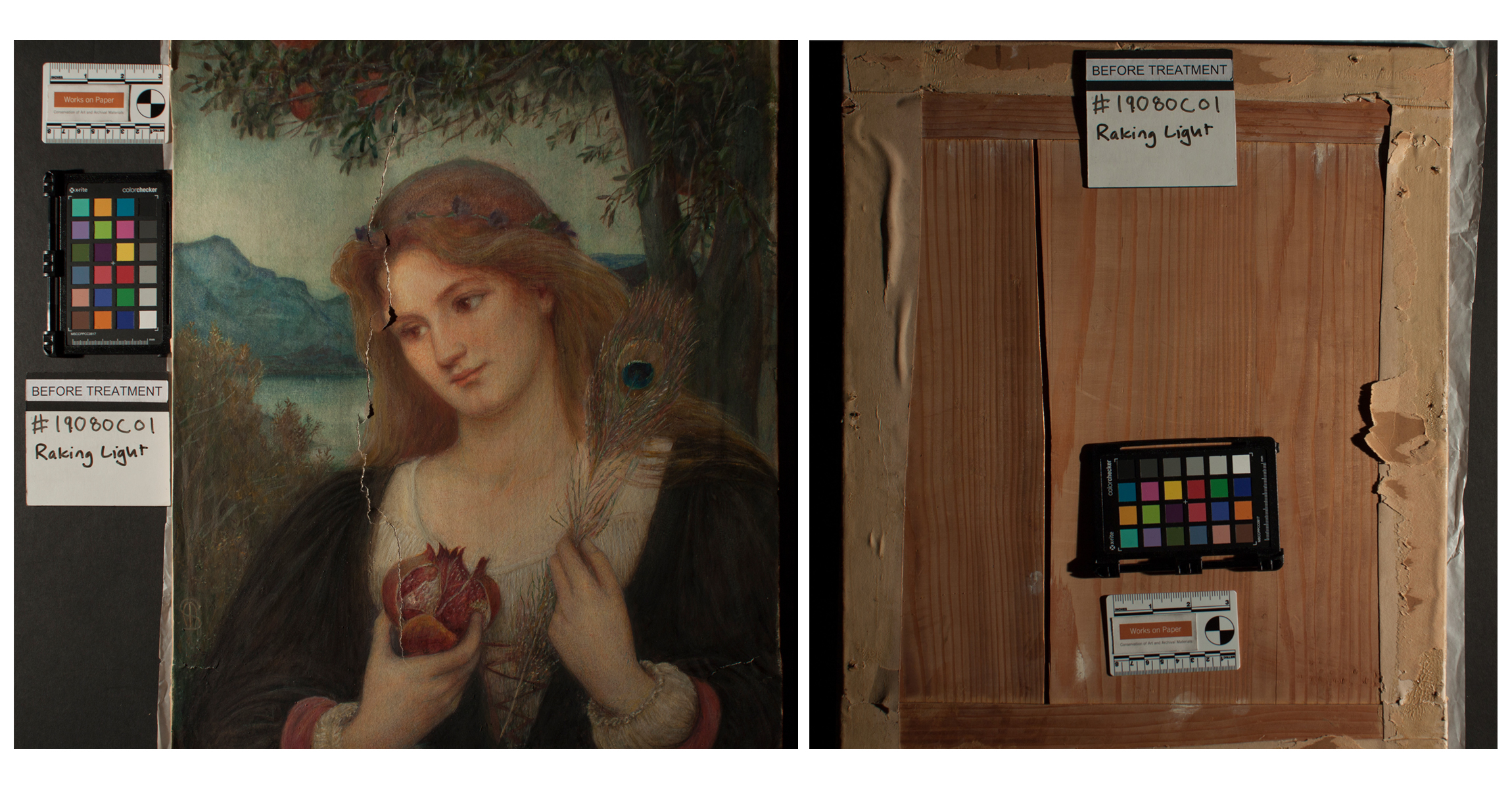

Craquelure, especially visible on either side of the figure’s face in the photograph on the left, refers to the pattern of cracking seen on the surface of a painting. It is predominantly caused either by the uneven drying of the artist’s materials (the canvas, the ground, the paint medium and the varnish) or the ageing and environment of the finished painting. Sometimes craquelure is in a very distinctive pattern: radiating from the edges, bullseye on the surface, or it can be very random as in this case, with non-directional cracks that have no relationship to the canvas weave, the stretcher or something that hit the surface. In general, the layers of materials that make up a painting become more brittle over time and have more negative reactions to swings in relative humidity and temperature.

The chemistry and physics of craquelure are very complex, but the end result is generally the same: the painted surface is very delicate, the paint is lifting from the canvas at the edges of each crack. Depending on the severity of the problem, some craquelure can be addressed from the front of the painting – a conservator wicks adhesive into the cracks with a tiny brush and secures the lifting cracks one by one with a small tacking iron or weights. In this case, since the craquelure was so widespread, advanced, and disfiguring, the painting had to be lined with an additional fabric using a heated suction table. This secures the lifting paint edges and flattens the surface overall, creating a more stable and more visually pleasing painting.

You can see how removing the yellowed varnish transformed the appearance of the painting.

From the Conservator's Notebook

Whitman Conservation

For more than a century, Landscape at Cortina has enjoyed a prominent location in Sarah Orne Jewett’s bedroom. But the work was showing its age and soot and missing elements were disfiguring the frame.

At right you can see the painting before (top) and after (bottom) conservation treatment. Click the hot spots to learn how conservators returned the painting to its former splendor.

Dirt and uneven varnish were obscuring the painting.

This frame was gilded using an oil size to adhere the gold leaf directly to the wood surface without using gesso to fill and smooth the wood. Because oil and gold are not sensitive to water, this frame could be cleaned with a water-based solution that was very effective.

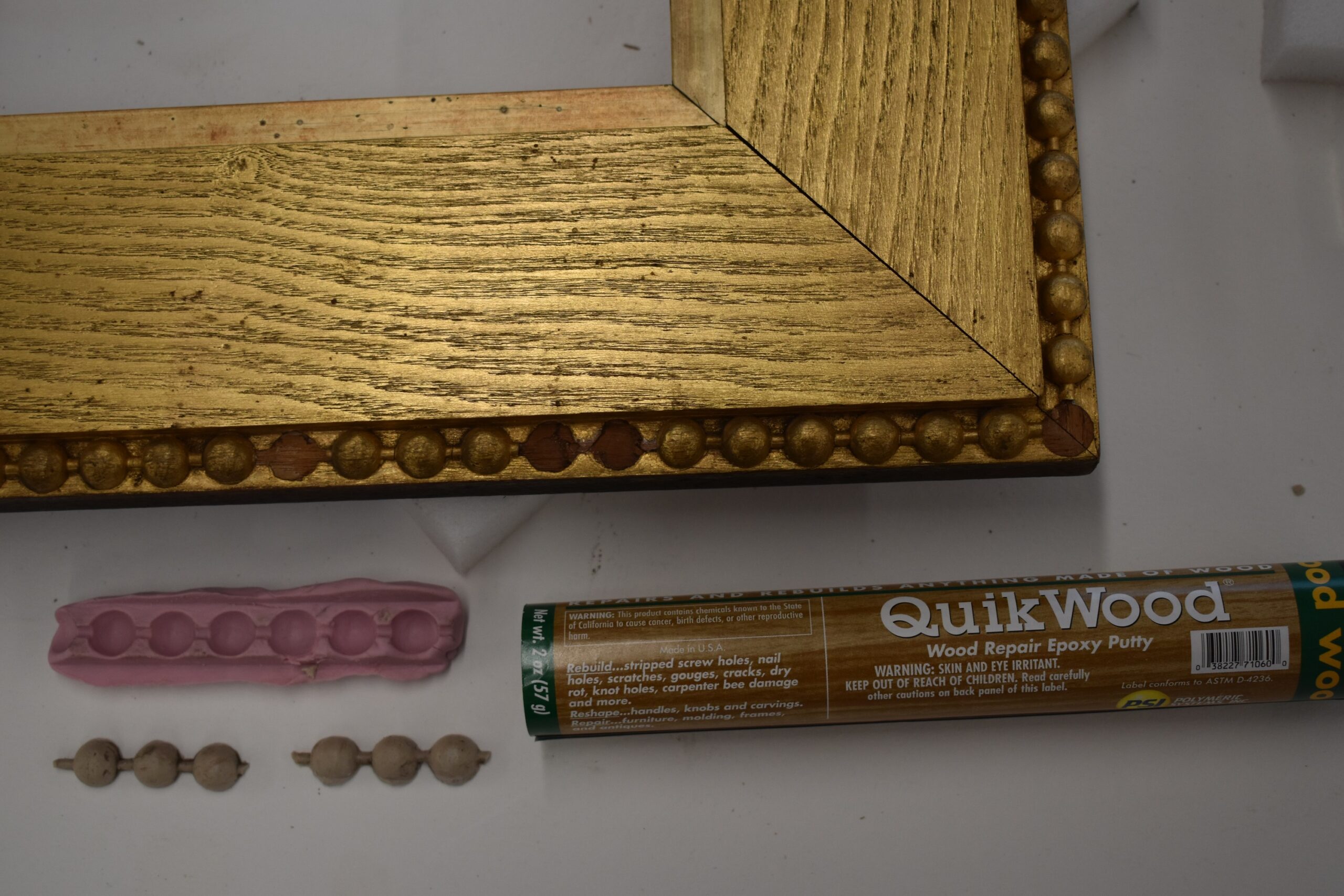

We made a mold of the decorative balls on the frame using dental putty.

Next we cast replica balls in the mold using wood epoxy putty.

We gilded the balls with a matching color of gold leaf.

Both the painting and the frame have come a long way. Now you can even see the yellow flowers in the grass!

to learn more

A Tale of Two Frames

Champney and Shapleigh

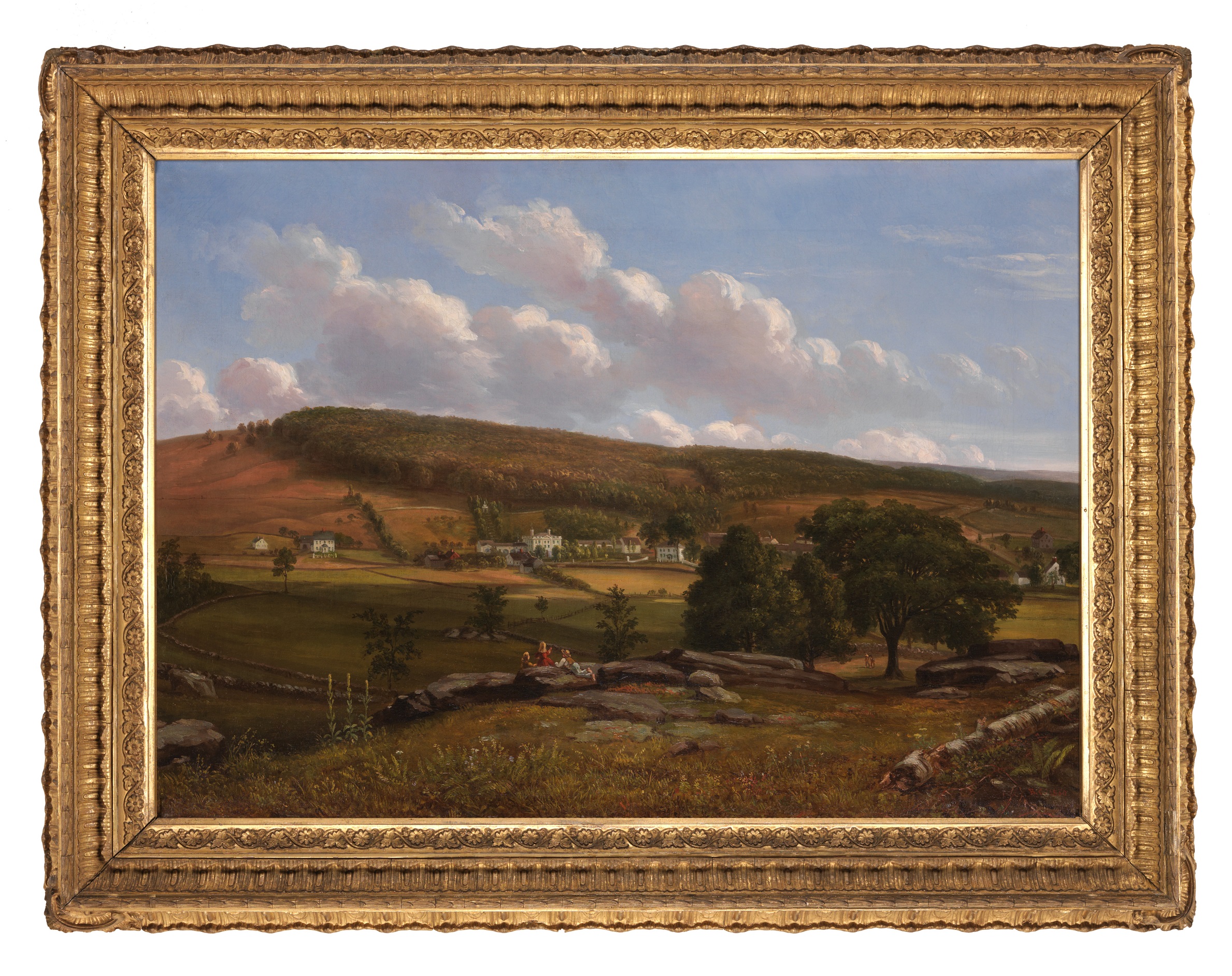

Right: Frank Henry Shapleigh (1842–1906), A Country Home, 1866, oil on canvas, 27 9/16 x 39 ½ in., Bequest of Amelia Peabody, 1985.662. Located in Gallery Two.

Take a look at the two paintings above. Both were made and framed around 1860, when this style of frame was very typical. All the decorative molding elements—the outermost bead, the serpentine braid, the incised cove, and the corner ornament—were cast out of a putty-like material containing linseed oil and whiting called composition or “compo.” The ability to cast decorative elements instead of carving them allowed for much more elaborate moldings, and several at a time, to be used on frames and thus keep costs down. Because the compo was smooth coming out of the mold, gesso and bole were unnecessary. A thin coat of oil size was brushed on and the compo could be gilded very quickly. The oil gilded areas could not be burnished, however, and therefore they appear matte. The thin strips between the different compo decorations, called flats, were made of wood coated with gesso and bole. These flats were burnished to produce a shiny contrast to the oil gilding and make for a more interesting frame.

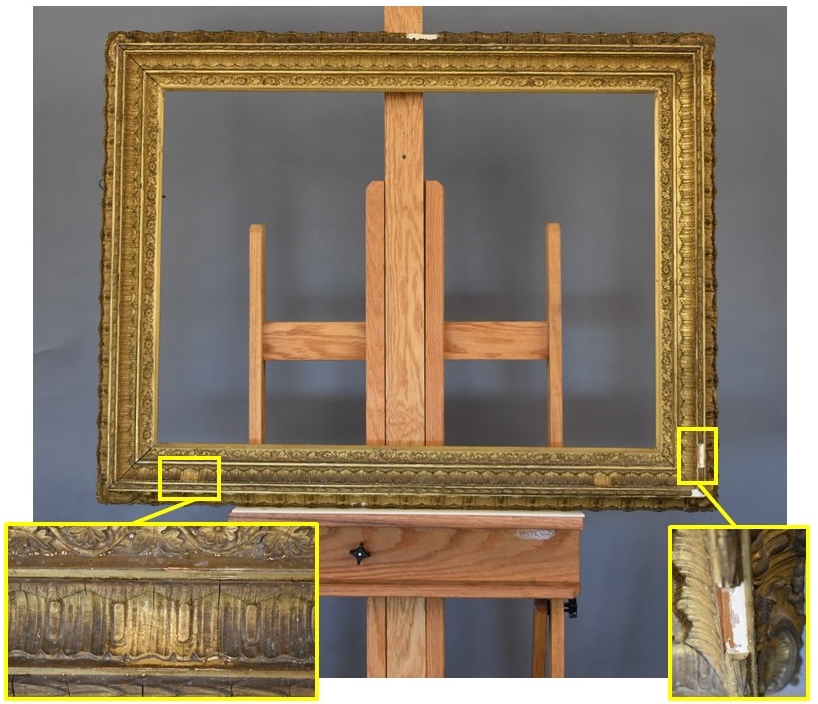

Benjamin Champney’s Mount Chocorua has hung at Barrett House (see Forest Hall in Gallery Two) for years and now shows its age. The compo on its frame has shrunk and cracked, and the gold has worn through from years of dusting. The oil size has dried and shrunk, causing faults in the thin gold layer and exposing the tan-colored compo below. Along the bottom edge and the high spots of detail, the exposed compo has darkened with dirt. This aged surface is very typical, natural, and acceptable considering its age.

The frame for A Country Home by Shapleigh looks remarkably good for its age – and so does the painting. Over 150 years old and no wrinkles! How can this be? The framed painting came to Historic New England in 1985. Sometime before then both painting and frame were given a facelift. The painted canvas was removed from its original stretcher and adhered to a Masonite board. This is a somewhat heavy-handed treatment, but the conservator likely had few other options to preserve what must have been a very delicate painting. The frame was likely in equally rough condition. Conserving a badly damaged frame so that it maintains its appearance of age is a very time-consuming, and thus expensive, process. It’s far easier to restore the frame to its original appearance by putting new gilding over old and that’s what happened when this was restored before it came to Historic New England. It looks fresh and new and much more “golden” than the frame on the Champney. This aesthetic was likely quite appropriate for the modern home it came from, but at Historic New England, we prefer items to have age-appropriate patina.

In the video below, Michaela Neiro describes the issues on the Champney frame that the conservation team worked to address.

Forest Hall

Benjamin Champney

A diagrammed image of the frame of Forest Hall shows the result of our cleaning test and a loss of compo section revealing the wood and gesso frame components below. See if you can find the reproduction areas on the finished frame.

Barnyard Scene, Sunset

Thomas Hewes HinckleyWhy are paintings lined? Click on the images in the gallery below to learn about this important process in paintings conservation. Zoom into the photographs for a closer look.

Conservation funds provided by Robert Bayard Severy in memory of his mother, Josephine McClintock Bellamy Severy (1914-2001)

Conservation photography by conservator Lisa Mehlin

Hera

Marie Spartali Stillman

This painting was made using materials that were typical to Marie Stillman but unique for her time period. The substrate was prepared more like it would be for an oil or tempera painting than for a watercolor. The heavyweight paper was laminated to another similar weight paper, then wrapped around a wooden panel with a main vertical center board and thinner horizontal boards adhered to the top and bottom (breadboard construction). The media Stillman used were watercolor, gouache, and likely water glass (sodium silicate), with oxgall added to some pigments.

This painting was made using materials that were typical to Marie Stillman but unique for her time period. The substrate was prepared more like it would be for an oil or tempera painting than for a watercolor. The heavyweight paper was laminated to another similar weight paper, then wrapped around a wooden panel with a main vertical center board and thinner horizontal boards adhered to the top and bottom (breadboard construction). The media Stillman used were watercolor, gouache, and likely water glass (sodium silicate), with oxgall added to some pigments.

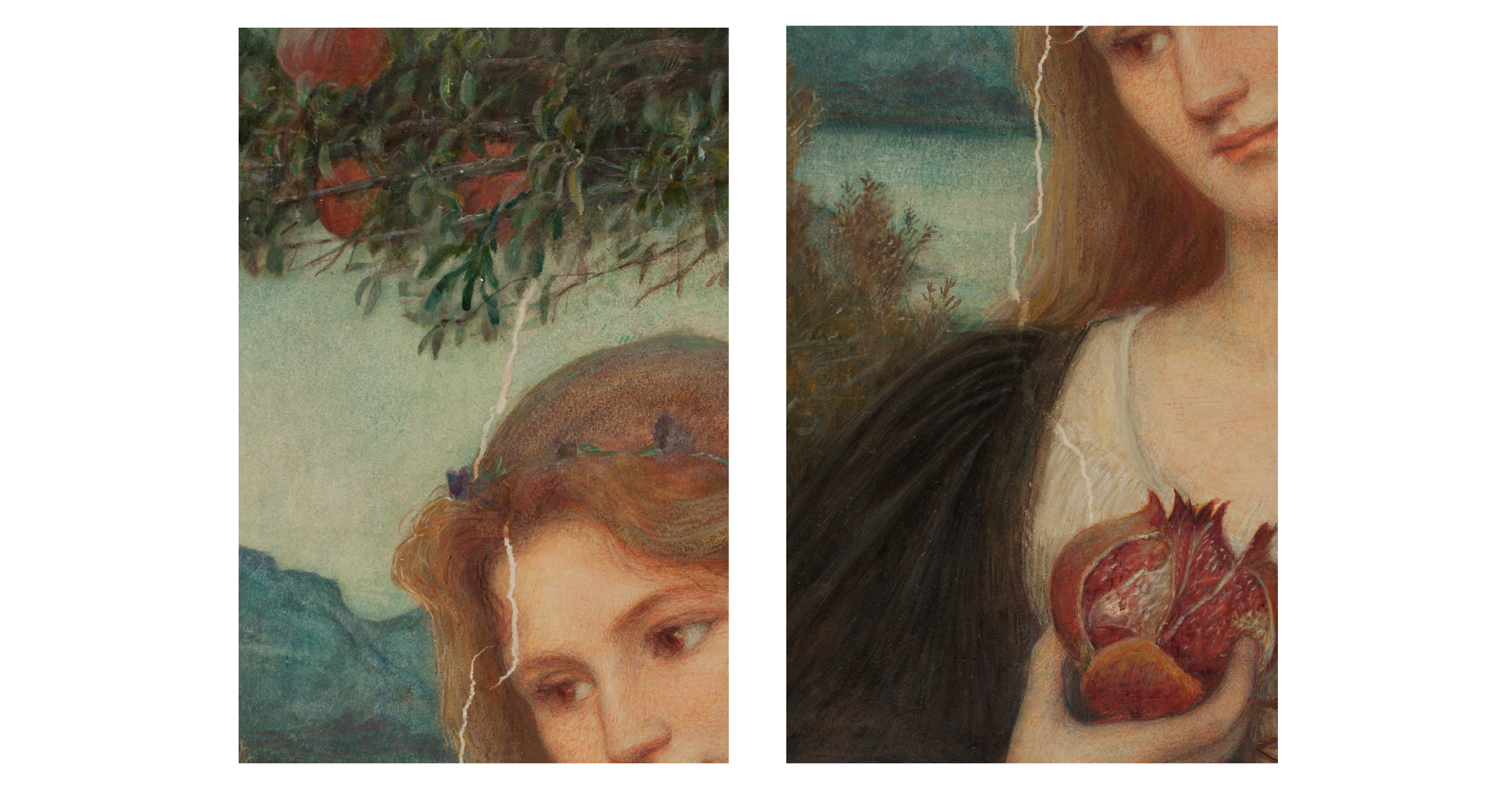

Likely due to a sudden and dramatic change in relative humidity, the panel cracked, creating a 15-inch vertical crack in the panel and therefore a related complex tear in the painted paper. Because the media is very water-sensitive and the construction of the paper around the panel is original to the artist, the decision was made to conserve the tear from the front of the artwork, leaving the paper on the board intact.

Dreams of the Past

Jehan-Georges Vibert

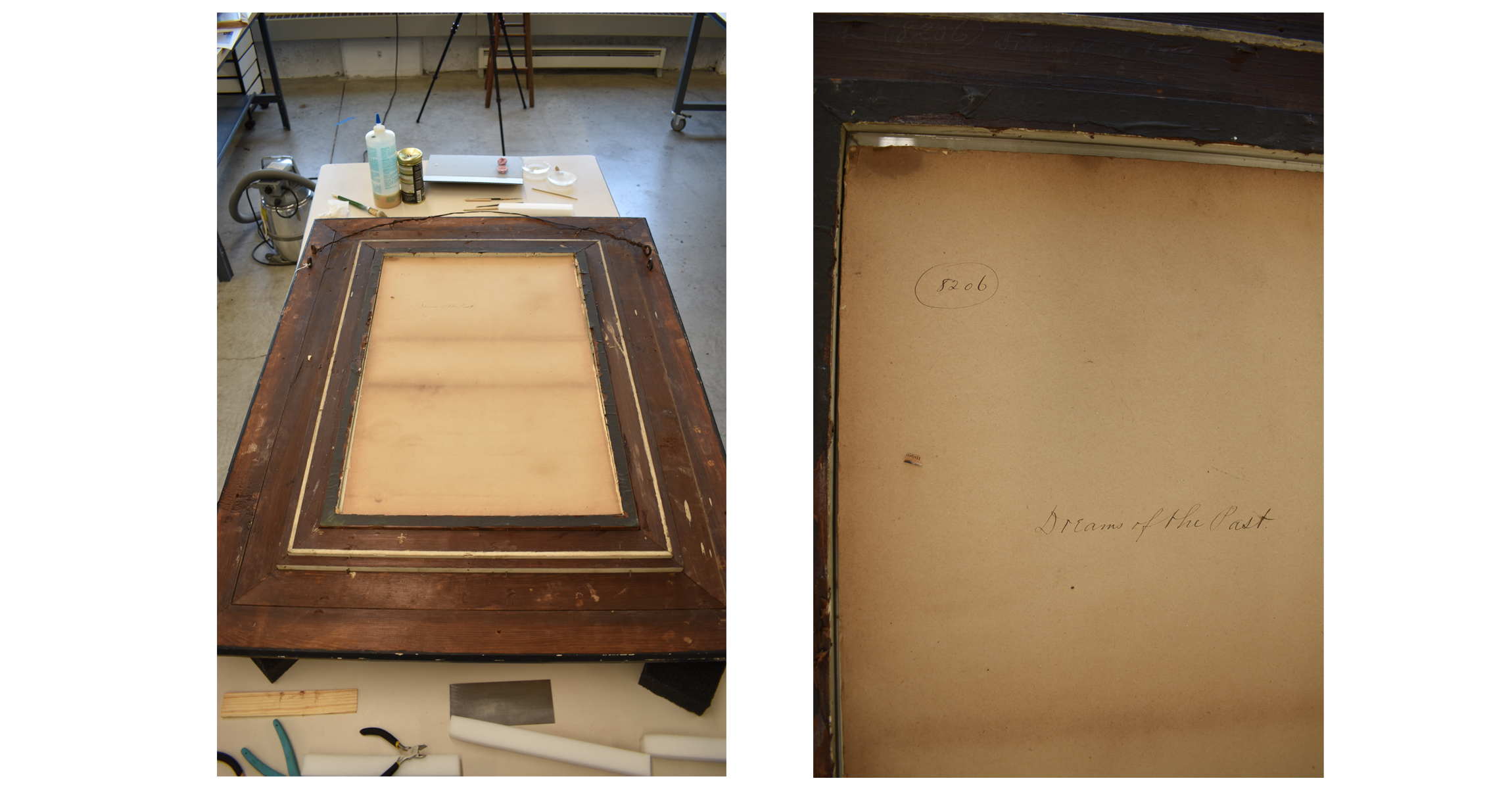

This complex frame is entirely water gilded. The process is called water gilding because water is used to reactivate the glue in the gray bole and allows the gold leaf to stick to the surface. Bole is a smooth, hard clay that allows the gold, when burnished, to become very shiny. Water gilding is more difficult than oil gilding because it requires several extra steps, so it is usually reserved for higher-quality frames such as this one.

This complex frame is entirely water gilded. The process is called water gilding because water is used to reactivate the glue in the gray bole and allows the gold leaf to stick to the surface. Bole is a smooth, hard clay that allows the gold, when burnished, to become very shiny. Water gilding is more difficult than oil gilding because it requires several extra steps, so it is usually reserved for higher-quality frames such as this one.

The gray bole is visible here along the lower edge of the frame. The gold leaf is so thin that even dusting the frame can cause it to wear away. The thick, parallel lines of gold are called “laid lines.” This occurs when the edges of the square leaves of gold overlap when they are laid on the frame to create a double thickness of gold. The decorative moldings are cast plaster. High spots are burnished to reflect light differently than matte areas and are especially beautiful when viewed by candlelight.

When we opened the back of the frame to replace the glass with UV filtering glass, we found a wonderful surprise…Someone wrote the title of the painting on the back! This information was previously unknown and thus an important discovery.

St. Servan Harbor

Edward Darley BoitHere you can see the before (left) and after (right) treatment images of Boit’s St. Servan Harbor.

What does it mean to “treat” a painting? There are many steps that the conservators take as they care for each painting. Click through the images below to learn more about how this painting was conserved.

Documenting Before Treatment

The very first step in any conservation treatment is to photo-document the object using a scale and color card. Ensuring the camera and lighting are the same before and after treatment highlights the work that was done and not any magic photographic manipulation. Note it is labeled BT for Before Treatment.