Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

Beauport

Beauport, the masterwork of interior decorator Henry Davis Sleeper (1878-1934), is often described as a “magical” place. Built in 1908 as a modest seaside retreat, Sleeper’s Gloucester, Massachusetts, home mushroomed by the 1920s into a forty-six-room maze whose scale, color, historical themes, and humor lend it a fairy tale quality. The secret to the magic was love. Sleeper surrounded himself on Eastern Point with a community of colorful, artistic, and devoted friends, at the center of which stood economist A. Piatt Andrew (1873-1936). It was this circle Sleeper sought to charm with his decorating fantasies, and Andrew above all. Smitten by this charismatic neighbor, Sleeper once wrote him: “I should never have taken the pains I did — nor would Beauport have existed — but for you.” Sleeper’s private quarters, tucked behind Beauport’s southern facade, faced Andrew’s home, Red Roof.

Henry Davis Sleeper

Wallace Bryant (1870–1953)

1906

Oil on canvas

Gift of Steven Sleeper, 1941.1703

Wallace Bryant painted Sleeper’s portrait soon after the designer met Piatt Andrew. The work’s unusual horizontal format places equal emphasis on Sleeper and the gleaming vase beside him, creating a double-portrait of collector and collection. Manifesting a color harmony for which Beauport would become famous — Bryant undoubtedly found Sleeper a demanding client on this score — the portrait is a catalogue of reds. From the oxblood vase and dusky red damask to his scarlet tie and rosy lips, Sleeper brandishes the signature color of Andrew’s home, Red Roof, with the grace of a matador.

The Development of Eastern Point

Gloucester Harbor

The Eastern Point summer colony, situated on a narrow, picturesque peninsula alongside Gloucester Harbor, was nearly twenty years old by the time of Henry Davis Sleeper’s arrival. In 1887 a group of investors named the Eastern Point Associates purchased Thomas Niles’s 450-acre farm on the Point, subdividing the land into 250 plots. Within two years, eleven Queen-Anne style cottages sprouted up on the peninsula, and by 1904 this area once considered beyond civilization featured the colossal, 300-room Colonial Arms Hotel.

On August 13, 1907, Sleeper bought Lot 101 from George Stacy, developer of the Colonial Arms. The fact that such a choice harbor-side lot remained available was likely due, in part, to its uncomfortable proximity to Stacy’s sprawling hotel. Yet for Sleeper the location could not have been more desirable. The closest available property to Piatt Andrew’s Red Roof, it lay separated from his home by just one owner, Caroline Sinkler, who became a close friend to both men. Like a portent of Beauport’s future prominence on the Point, on New Year’s Day 1908 the towering Colonial Arms burned to the ground. Sleeper’s home, still under construction, lay unscathed.

Beauport

Wrong Roof (Caroline Sinkler House)

Red Roof (A. Piatt Andrew House)

to learn more

Take a Virtual Tour of Beauport

Click the PLAY button to begin your visit. Start exploring by clicking in the direction you want to go or skip around by clicking on the circles on the ground. To look around a space, simply click, hold, and drag in any direction.

Navigate quickly between rooms and floors using the icons found in the lower left corner.

A. Piatt Andrew

Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942)

1903

Oil on canvas

Gift of Red Roof Associates, 1991

Cape Ann Museum

The celebrated painter Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) was a close friend to both Piatt Andrew and Sleeper. Her striking portrait of Andrew presents the Harvard professor in his academic robes, yet her subject defied ivory-tower stereotypes. Boasting matinee-idol good looks, profound charisma, and a passion for strenuous sports, Andrew led an adoring coterie that included a number of athletic younger men. Immediately drawn to Andrew himself, Sleeper bought land near the professor’s home in 1907. Shy and often unwell, the designer possessed none of the qualities of Andrew’s outdoorsy beaux; throughout the following decades he held Andrew’s attention, instead, with his ever- expanding home.

The American painter Cecilia Beaux trained in the 1870s at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, then under the direction of Thomas Eakins, and subsequently at the Académie Julian in Paris. Sometimes unfairly labeled “the female John Singer Sargent” for the similarities of their portrait style, Beaux won major juried prizes by the 1890s and in 1895 she became the first woman to join the faculty of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

A regular summer visitor to Gloucester beginning in the 1880s, Beaux built her home Green Alley on Eastern Point in 1906. A nearby neighbor and close friend of Piatt Andrew’s, she disguised their eighteen-year age gap by shaving eight years from her birthdate. Clearly drawn to handsome, unavailable gay men, the never-married Beaux was likely bisexual herself. (In 1906 she ended an intense, apparently romantic, five-year relationship with Dorothea Gilder, a woman twenty-seven years her junior). Her affection for Andrew could take playful forms, but it could also manifest itself in a less sympathetic light. After a 1908 visit with Andrew and Henry Davis Sleeper in New York, Beaux recorded in her diary that, however much she enjoyed seeing the men together, “I have to remember the one appalling FACT.”

Curator's View

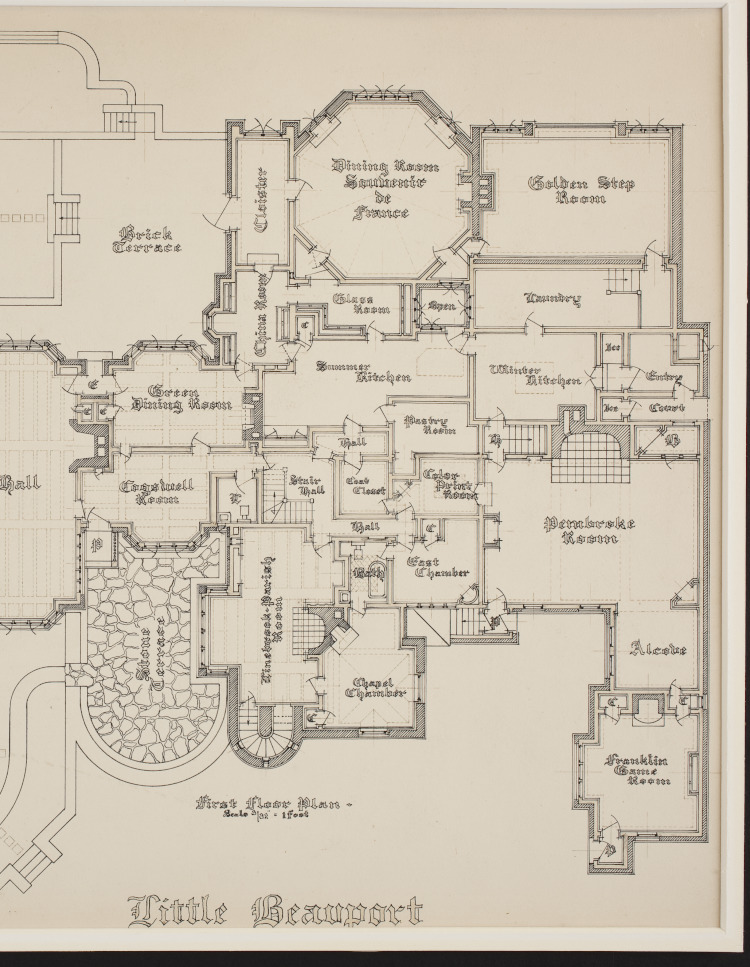

Two Poles on Eastern PointFirst Floor Plan of Beauport

Halfdan M. Hanson (1884-1952)

Gloucester, Massachusetts; 1925

Paper and ink

Gift of Constance McCann Betts, Helena Woolworth Guest, and Fraiser W. McCann, 1942.2153

Architect Halfdan M. Hanson (1884-1952) prepared this plan of Beauport’s first floor in 1925, once the home had reached its approximate present size. Trained as a carpenter and woodcarver, the Norwegian native built Sleeper’s 1908 house and continued to oversee its expansion until the designer’s death in 1934. Hanson’s plan reveals his nostalgia for Beauport’s earliest incarnation. Always using the home’s retired name “Little Beauport” in his correspondence with Sleeper, Hanson mislabeled the large room at the center of his 1925 plan as the Hall. This former centerpiece of the 1908 home, once a medieval-themed space, had by 1923 become the China Trade Room.

Writing Sleeper in 1921, Hanson reminisced:

It makes quite an interesting affair when you… look back over the various circumstances associated with each particular addition and renovation as they in turn took place from year to year…. It does not seem possible to duplicate again anywhere, Little Beauport, because into it has been placed your very Iife, and it breathes in every nook and corner of the whole place… as I look back over those years, it moves me very much.

Sleeper and Humor

Henry Davis Sleeper’s interiors targeted the emotions rather than the intellect, conjuring visual “moods” with little regard for historical authenticity or even the intrinsic value of individual objects. Providing a glimpse of his criteria for collecting, Sleeper once offered an object to a client with the caveat, “if it gives you no emotion” he should reject it.

Campy amusement ranked high among the emotions Sleeper conjured, evidenced by the many visual jokes he orchestrated at Beauport. Consider the collection of glass balls he placed in his Red Roof-facing window—as much a satire about Piatt Andrew’s virility as they are an homage to nineteenth-century craft—or the military epaulette he placed in the Admiral Nelson Room, converted into a lady’s pincushion. Speaking of the wood stove he installed in Beauport’s Stair Hall, cast in the shape of a standing George Washington, Sleeper reportedly said: “It’s wonderful to sit here and see him get hot, he is slow to anger, but so comforting.”

Shadow Box with Mourning Scene

Likely England, 1825-35; Watercolor, silk, felt, hair, paint, paper, ink; Gift of Constance McCann Betts, Helena Woolworth Guest, and Fraiser W. McCann, 1942.2686.

Piatt Andrew once asked his neighbor Caroline Sinkler, “Is Harry [Sleeper] as ribald and shocking as ever?” As this mourning picture confirms, Sleeper’s sense of humor occasionally bordered on the bawdy. Hung in his private writing nook, the scene includes two men apparently locked in a passionate embrace. Homoeroticism was hardly the artist’s original intent, but under Sleeper’s eye, the work — like every other artifact in the house — was cast anew.

Octagon Room

In 1920, Sleeper wrote his friend, art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924), that he had “all the details visualized” for Beauport’s Octagon Room. When he assembled such incongruous objects as this stuffed ibis, toleware tray, leather knife box, and camera obscura, Sleeper prized them not for their intrinsic value but rather for their contribution to the room’s symphony of reds. The knife box was a gift, and likely an inside joke, from Gardner herself. Though not strictly red, it once belonged to a cardinal.

Click on the image at right for full view and zoom into objects below.

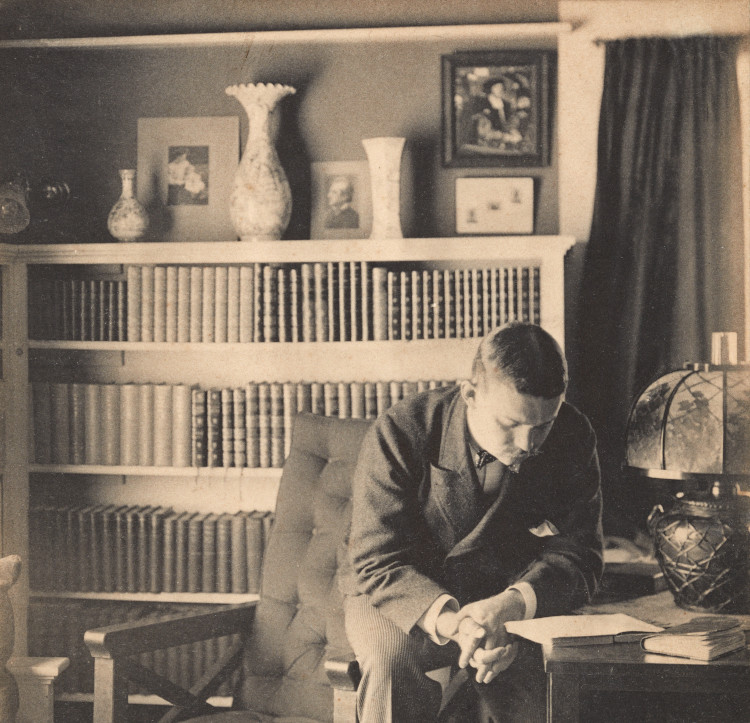

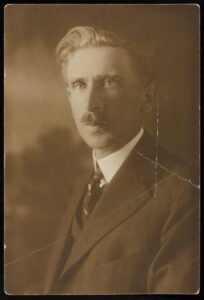

Guy Wetmore Carryl at Shingle Blessedness

Maker unknown

Swampscott, Massachusetts, c.1900

Gelatin silver print

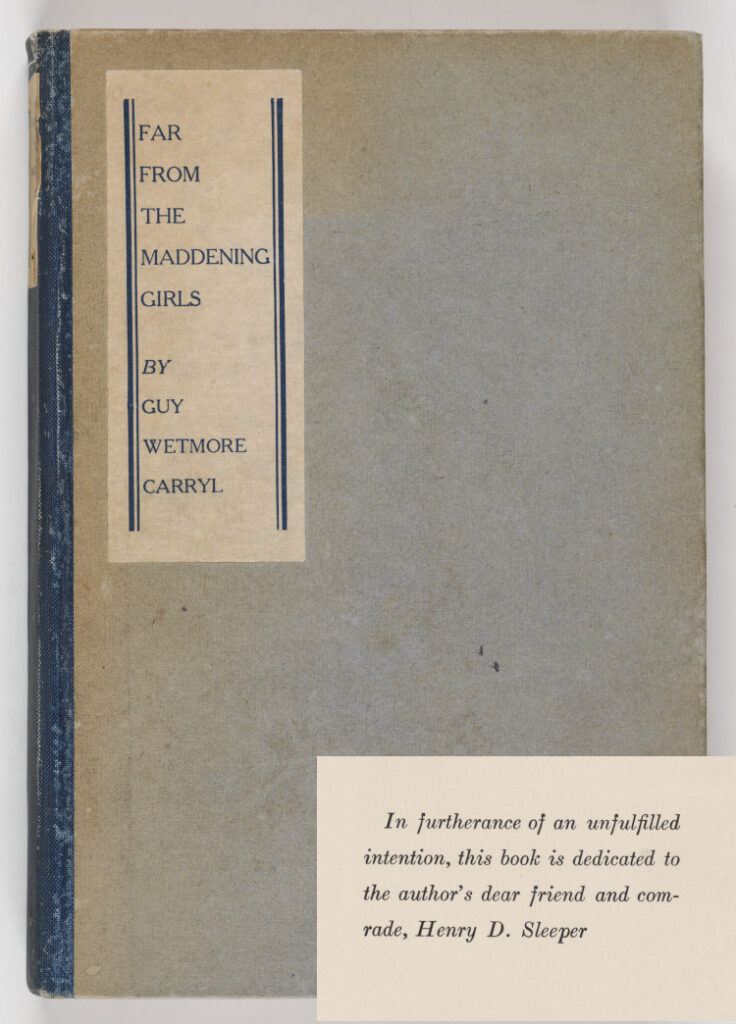

Satirist Guy Wetmore Carryl (1873-1904), identified by one contemporary as Sleeper’s “closest personal friend,” was likely the designer’s first love. Carryl appears here in his Swampscott, Massachusetts, home, a bachelor retreat he named Shingle Blessedness; when he attempted to save the house from fire in 1904, Carryl sustained mortal injuries. His posthumously published novel, Far From the Maddening Girls (1904), celebrates a confirmed bachelor’s project to design his own home. Carryl dedicated the book to his “dear friend and comrade” Sleeper, “in furtherance of an unfulfilled intention.”

Guy Wetmore Carryl (1873-1904)

Henry Davis Sleeper and writer Guy Wetmore Carryl met not long after Carryl’s 1901 return from Paris, where he had served as a correspondent for a number of popular American magazines. Several years older than Sleeper he was urbane, handsome, bookish, and passionate about his home—in other words, he embodied all the qualities Sleeper would later recognize in Piatt Andrew. A writer of wide-ranging talents, Carryl was a playwright, journalist, poet, and satirist; today he is best known for such mildly risqué verse as Mother Goose for Grownups (1900) and Grimm Tales Made Gay (1902). Sleeper described him as a man “of poetic instincts … a genial and most communicative companion.”

The physical extent of the men’s relationship may never be known, but Sleeper’s emotional attachment to Carryl is clear. He kept framed photos of the writer, collected several volumes of press clippings about his work, and was a frequent guest at Carryl’s Swampscott home. It is tempting to see in their relationship a foreshadowing of Sleeper’s later crush on the romantically unavailable Andrew—and yet Carryl’s enigmatic dedication to Sleeper in his posthumously-published novel, Far From the Maddening Girls (1904), suggests at least some form of romantic reciprocation.

Beauport in the Press

Beauport has always attracted wide press coverage. In 1929 Country Life writer Reginald T. Townsend composed this extensive tribute to Beauport, accompanied by full-color reproductions of William Ranken’s paintings of the home. Entitled “An Adventure in Americana,” the article declares Sleeper “is more than a mere collector. He is more than an antiquarian. He is at heart an artist.”

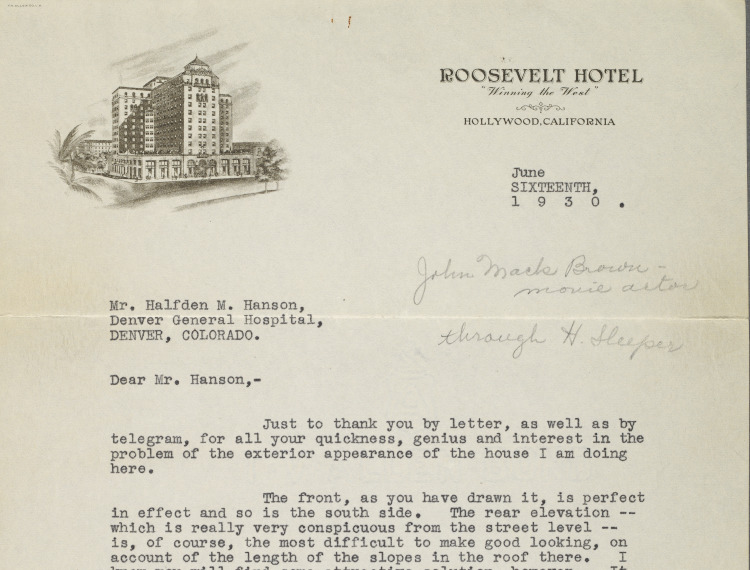

Letter from Henry D. Sleeper to Halfdan M. Hanson

Page One

Hollywood, California, June 16, 1930

Pencil and ink on paper

Gift of Phyllis (Hanson) Ray, Linday (Ray) Brayton, and Jacqueline (Ray) Newton, 1983-85

Sleeper’s clients in the 1930s spanned from the Vanderbilt family to Joan Crawford, yet nowhere else did he achieve Beauport’s eclectic vision. In this 1930 letter to Halfdan M. Hanson, Sleeper included a sketch for actor Johnny Mac Brown’s Hollywood home, a colored glass installation that evoked — but likely did not surpass — Beauport’s Amethyst Passage.

Transcription:

Dear Mr. Hanson, –

Just to thank you by letter, as well as by telegram, for all your quickness, genius and interest in the problem of the exterior appearance of the house I am doing here.

The front, as you have drawn it, is perfect in effect and so is the south side. The rear elevation – which is really very conspicuous from the street level – is, of course, the most difficult to make good looking, on account of the length of the slopes in the roof there. I know you will find some attractive solution, however. It really has to be particularly good, because most of the living will be on the terrace in front of this façade.

The gables as you have suggested them in your partial drawing, looked right in proportion. How would it be to have a little piazza or gallery, with a railing on the sides and front under the windows of these gables – something similar to those above the court-yard entrance of my house at Gloucester?

For the sake of economy, it is necessary that we use stock windows, the architect here tells me. These are made in England, but come, of course, in certain sizes, and are made of steel, and similar in appearance, to the leaded glass casements.

I have asked Mr. Arthur Kelly – the local architect here, to have his office get in touch with you, in regard to any and all questions which may be necessary for them to know, in order to bring the house and its appearance into conformation with your drawings as shown.

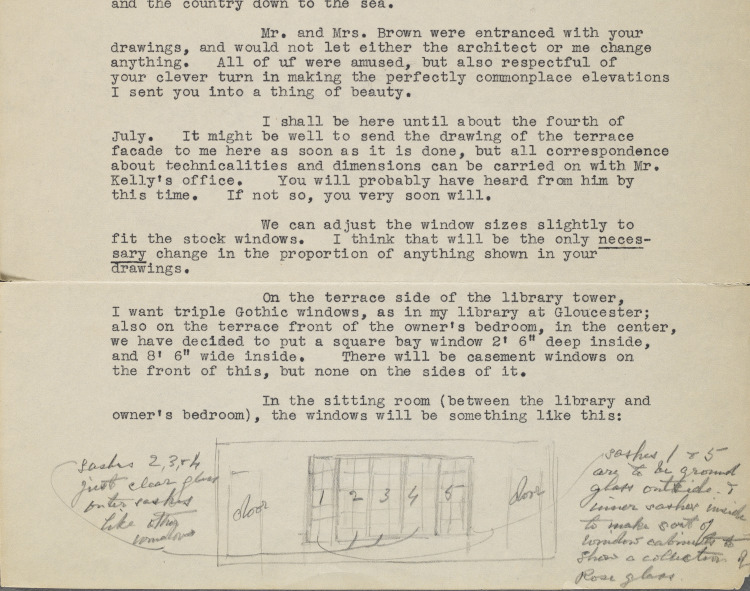

Page Two

Transcription:

It may interest you to know that the owner of this house is John Mack Brown – a very dear friend of mine. He is our most successful and attractive of the moving picture stars, as you probably know.

The house is to be at Ledgemont Park – part of Beverly Hills – on the edge of Los Angeles, and is built on sort of table land, 150 feet above the surrounding country, with a wonderful view from the terrace, of Los Angeles, and the country down to the sea.

Mr. and Mrs. Brown were entranced with your drawings, and would not let either the architect or me change anything. All of uf [sic] were amused, but also respectful of your clever turn in making the perfectly commonplace elevations I sent you into a thing of beauty.

I shall be here until about the fourth of July. It might be well to send the drawing of the terrace façade to me here as soon as it is done, but all correspondence about technicalities and dimensions can be carried on with Mr. Kelly’s office. You will probably have heard from him by this time. If not so, you very soon will.

On the terrace side of the library tower, I want triple Gothic windows, as in my library at Gloucester; also on the terrace front of the owner’s bedroom, in the center, we have decided to put a square bay window 2’ 6” deep inside, and 8’ 6” wide inside [sic]. There will be casement windows on the front of this, but none on the sides of it.

In the sitting room (between the library and owner’s bedroom), the window will be something like this: [below is a pencil sketch showing a series of five casement windows between two doors, all/numbered; with handwritten marginal notes by Sleeper]

sashes 2, 3, + 4 just clear glass outer sashes like other windows

sashes 1 & 5 are to be ground glass outside + inner sashes inside to make sort of window cabinets to show a collection of rose glass