Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

Charles Bowie's Office

The butler’s office serves as a center of operations

This room—labeled the “man’s room” on the floor plan—was the office of the butler, the most senior staff member in the household. The butler managed the operations of the house and would have been in close communication with W.E.C. Eustis. This office was used for meeting with vendors, interviewing new staff to hire, writing correspondence, and planning for family travel. Charles Bowie worked for the Hemenway and Eustis families for decades and was a valued member of the staff. As a founding member of the Ward 9 Club, his work challenging establishment politics in nineteenth-century Boston helped to write an early and unique chapter in the history of Black activism in New England. Read more about his work in the sections below or tap Ward 9 Club in the bar at the top of the screen to find it now.

China Closet

Opposite this room is the china closet, sometimes referred to as a butler’s pantry. In addition to storing dishes, this space was used for plating food, which was sent through the “pass through” opening from the kitchen. It would then be delivered into the dining room while keeping separation between the active kitchen space and the family and guests.

The staff spaces of the mansion had all the latest technological advances. Learn more about the modern technologies on view in the china closet and servant’s hall.

Elevator

The builders’ plans for the mansion indicate that was originally an elevator installed in the house, which would have been a simple cab that was used primarily for wood. An electric sawmill in the basement was used to cut wood to the proper size. The current elevator cab was upgraded in the early twentieth century.

Charles Bowie

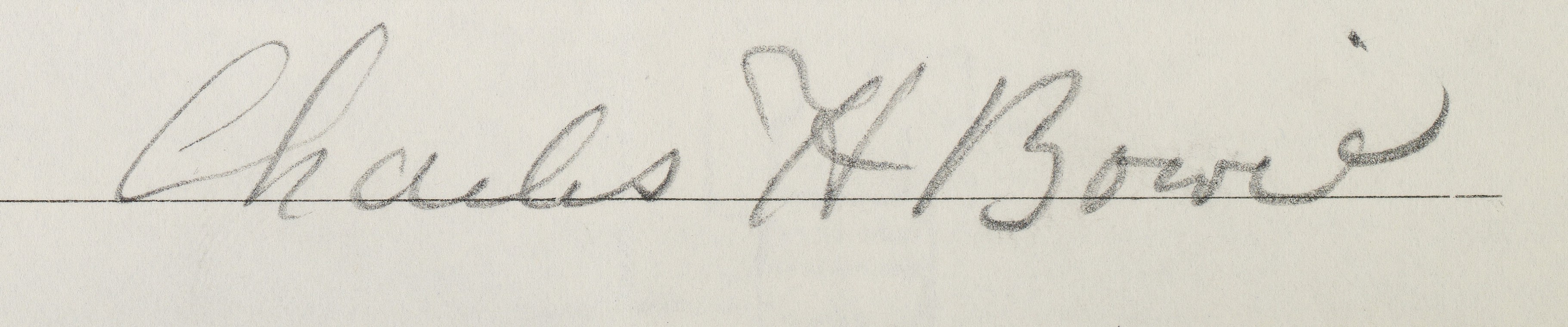

Signature from Charles Bowie’s paystub, 1915. There are no known photographs of Charles.

Charles Bowie was the butler for the Eustis Estate from 1904-1928, though he started working for Mary Hemenway, the mother of Edith Eustis, in the 1880s. His story started, however, far away from the streets of Beacon Hill in Boston. Charles was born in 1860 in Maryland and his family had likely been enslaved by the prominent Bowie family which included Maryland’s thirty-fourth governor, Odin Bowie. The Bowies enslaved large numbers of people at their Bellefield, Fairview, and Mattaponi plantations in Prince George’s County between 1810 and 1865. Charles was raised at or near one of these properties though it is unclear if he was enslaved. Due to changes in agricultural production in the area over the course of the nineteenth century, Maryland’s enslavers sometimes freed their enslaved workers and hired them seasonally rather than paying for their care year-round. By the time Charles was born in 1860, plantation work was often done by paid Black and white workers alongside those who were enslaved.

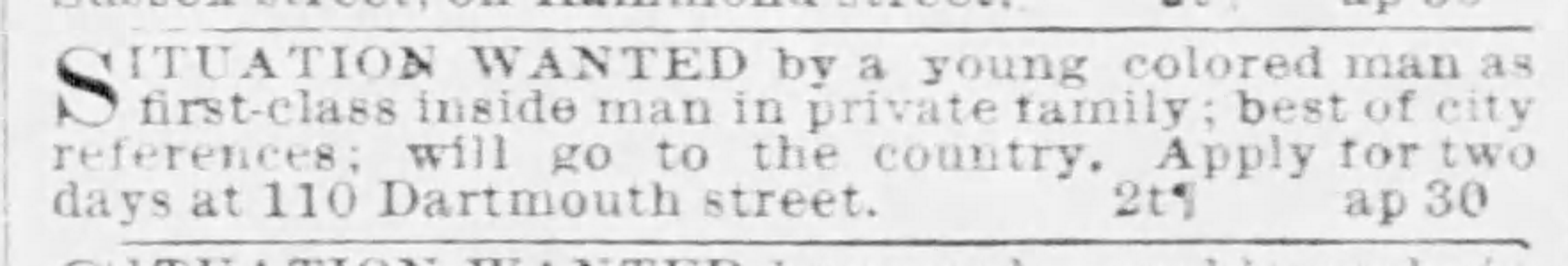

Charles arrived in Boston in the early 1880s; he had left his parents and siblings in Maryland and traveled alone to New England seeking domestic work. In the early 1880s he found work in several hotels and private homes as an “inside man,” a term that implied a variety of tasks within one position, from janitorial to butlering. In 1888, Charles published an advertisement in the Boston Evening Transcript seeking his next position which read, “Situation wanted by a young colored man as first-class inside man in private family: best of city references; will go to the country. Apply for two days at 110 Dartmouth.”

This advertisement may have been answered by wealthy widow Mary Hemenway, because shortly afterward Charles began working at her home on Beacon Hill, 40 Mt. Vernon Street.

Views of 40 Mt. Vernon Street

Mary Hemenway’s Beacon Hill Mansion

Augustus Hemenway commissioned architect George Minot Dexter to design the house in 1850. The large brownstone building had subtle elements of Greek, Renaissance, and Egyptian Revival styles, but the exterior was understated, letting size speak for itself. In contrast, the grand interiors were finished with elaborate woodwork, elegantly furnished, and soon filled with objects and art pieces curated by Mary. With its spacious rooms, tall ceilings, and large windows, Augustus’s modern mansion made a visible statement about his considerable wealth and power. After his death, Mary continued to live there and even operated some of her charitable endeavors out of the property.

Click the hot spots for more information on this image and see other images below.

Mary Hemenway ordered this custom chair as a perfect spot to read to her grandchildren. It was later brought to the Eustis Estate in Milton, and can be found on the second floor landing.

Mary Hemenway displayed paintings on the parlor chairs, explaining: “My pictures are my friends. I want them to sit on my chairs.”

A mix of patterns on the wall and ceiling was a hallmark of the lavish decorative style of the mid-19th century.

to learn more

After Mary’s death in 1894, Edith Eustis was given the life rights to use the Mt. Vernon Street house. Charles stayed on and oversaw the staff while taking direction from W.E.C. Eustis, who sent his instructions via correspondence from Milton. Around this time, Charles began making investments in his own future in Boston. In Mary Hemenway’s will he was left $500 in “recognition of his faithful services.” With this major sum (about $18,000 in today’s dollars), he purchased a home in Dorchester. In that same year Charles began to explore local ward politics in the West End of Boston.

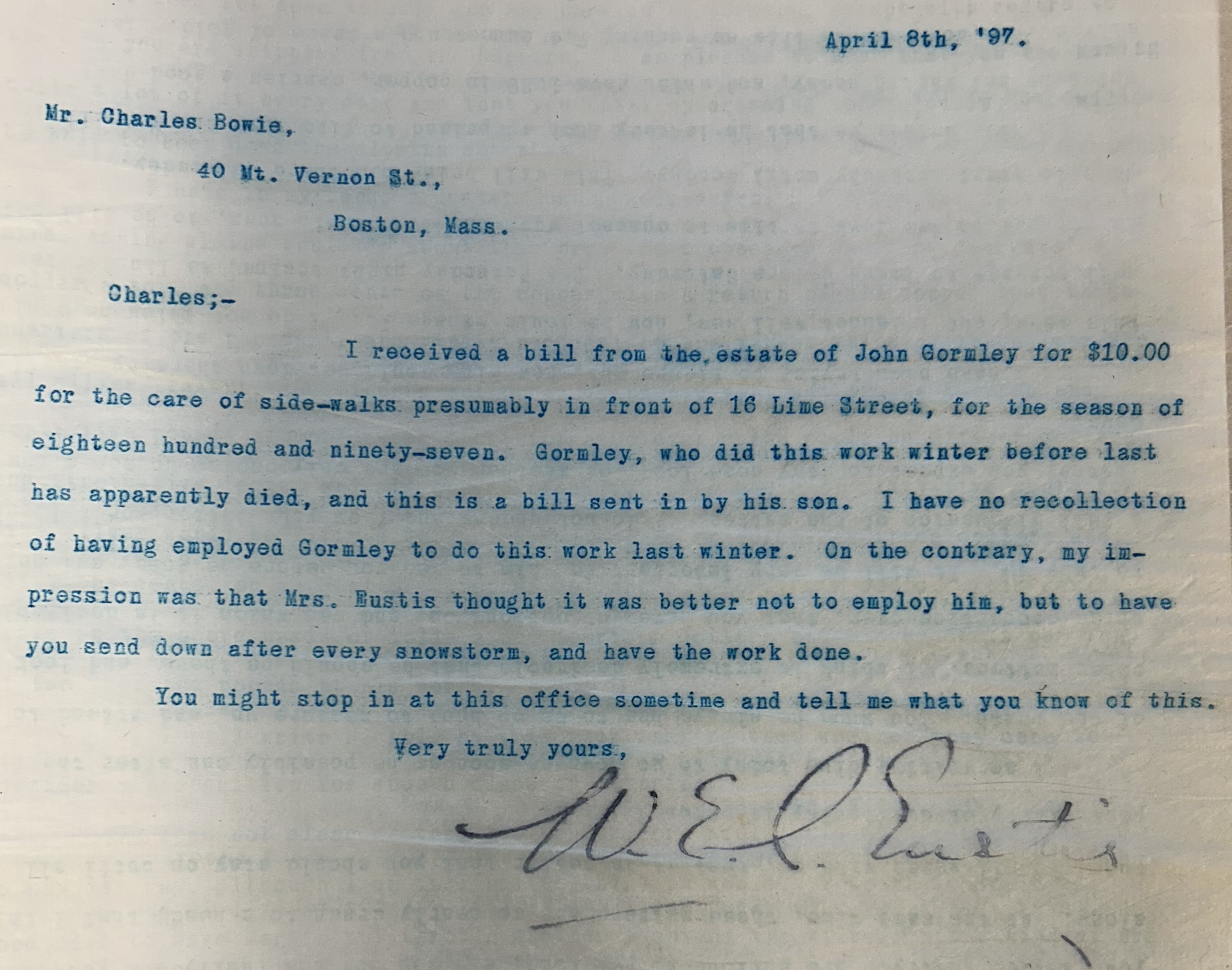

Letter written by W.E.C. Eustis to Charles Bowie when he was managing 40 Mt. Vernon Street.

Black Democrats Ward 9 Club

Charles’s ambitions extended beyond domestic work. In the mid-1890s he and a group of his peers began to explore Black political work in Boston, forming the Black Democratic Ward 9 Club in 1895. The sixteen founding members worked quickly to establish a presence in Boston and July of that year saw several announcements of their activities in local newspapers, including one in The Boston Globe stating that their objective would be “to perpetuate Democratic principles and to support Democratic nominees in state and municipal a !airs,” and noting that “the members express themselves as being determined to do honest work for the advancement of the party, and have pledged themselves to do all in their power to elect Democratic nominees.”

By the 1880s Ward Nine had long been a historical center of Black life in Boston, and it housed up to half the city’s Black population near Mass General Hospital by the late nineteenth century. This geographic concentration of Black voters gave Ward 9 particular political leverage and provided an opportunity for Black politicians to rise in racially divided Boston. The phenomenon did not go unnoticed, however, and as the notion of a biracial democracy stalled, Boston began to redraw its maps, redistricting in 1875 and 1895 and finally creating a divide in the West End that moved many of its Black residents into Ward Eleven. This move purposefully diluted the concentration of Black voters within a single district and greatly diminished their political influence.

It was at this moment that Charles Bowie appeared to begin engaging with local politics, perhaps motivated by the redistricting. His choice to align himself with Democratic politics makes him part of a small subset who believed that the Republican promise of Reconstruction had already failed and that policies to advance the rights of the previously enslaved did not go far enough, particularly as related to voting rights. Not content with the spoils of continual compromise, these advocates argued for race over party and abandoned the Republican platform, pursuing electoral politics as a more direct pathway towards the equity they sought.

Over the next five years the club pushed back against Black political suppression, working to place their members in elected positions in Boston with limited success as the promise of Reconstruction faded into the Jim Crow era. Charles was nominated for the Massachusetts Common Council in 1896, although he didn’t win. In 1898, he was nominated by the 11th Ward Democratic caucus for the Common Council. The Ward 11 Club seems to have disappeared by 1900.