Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

Tattooing as Spectacle

From the 1870s to the 1920s, America’s industrial cities filled with immigrant and native factory workers eager for amusement. With wages in their pockets and precious leisure hours to fill, this growing, increasingly diverse urban working class created a demand for new forms of popular entertainment that could transcend differences in language, education, and culture. Spectacle—the sensationalized display of the odd, the exotic, and the transgressive—offered universal, irresistible appeal. As dime museums, burlesque theaters, cinemas and peep shows flourished in the gritty entertainment districts of America’s cities, enterprising men and women found that a living could be made from exhibiting their tattooed bodies—and from the spectacle of tattooing itself.

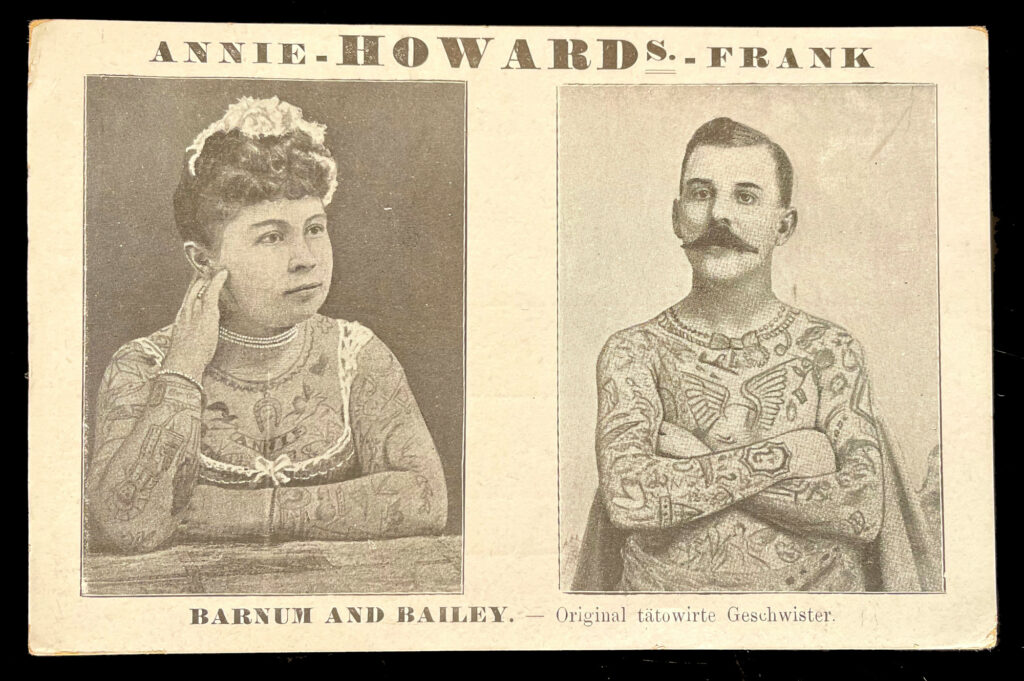

Frank and Annie Howard Promotional Postcard

Germany, c. 1900

Collection of Historic New England

Frank and Annie Howard hit the big time in 1888, joining Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth for the circus’s only nationwide tour. Annie made history as the first tattooed woman to tour with Barnum & Bailey. Between 1897 and 1902, the Howards rejoined Barnum & Bailey for an extended tour of Germany, Austria, England, Scotland, and Wales.

The Howard Family

Franklin Howard Packard, and his wife, Anna Jane Morrison Packard took on full-body “suits” of hand-pricked tattoos around 1884, while living in Chicago. They soon adopted the stage names Frank and Annie Howard. The couple trouped on the carnival and dime museum circuits throughout New England and the Midwest through 1896, performing solo or in “congresses” of tattooed people. After his performances, Frank prolonged the spectacle—and supplemented his income—by tattooing volunteers from the audience.

Frank and Annie’s daughter, Carrie Minnie Frances Howard (1883–1923), joined the circuit when she was two years old, appearing with her parents as a “spotted child.” Over the years Carrie performed as a snake charmer, a trained bird handler, a cornet player in the circus band, and—under the stage name “Ivy”—as the “Moss-Haired Girl.”

Selling “pitch books,” novelty items, and souvenir photographs like these brought sideshow performers a little extra cash.

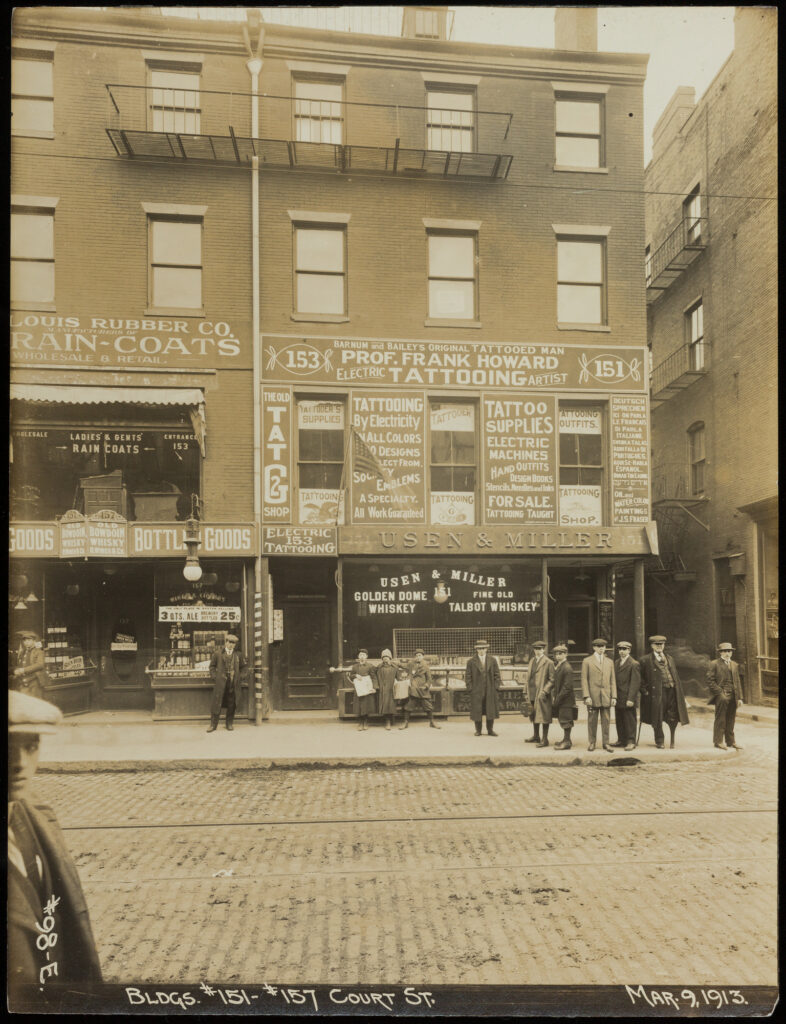

Rhode Island natives Frank Howard and his wife Annie, America’s premier early tattooed showfolks, performed regularly at Austin & Stone’s Dime Museum. Two tours with Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth, in 1888 and 1897, established the Howards as world-class entertainers. Frank, a consummate self-promoter and a savvy businessman, later spun that fame into highly profitable ventures as a tattoo artist, tattoo shop proprietor, and dealer in mail-order tattoo supplies.

Austin & Stone’s Dime Museum Letterhead

Austin & Stone’s Dime Museum Letterhead

Boston, c. 1900

Reproduction image courtesy of the Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department, Brandeis University

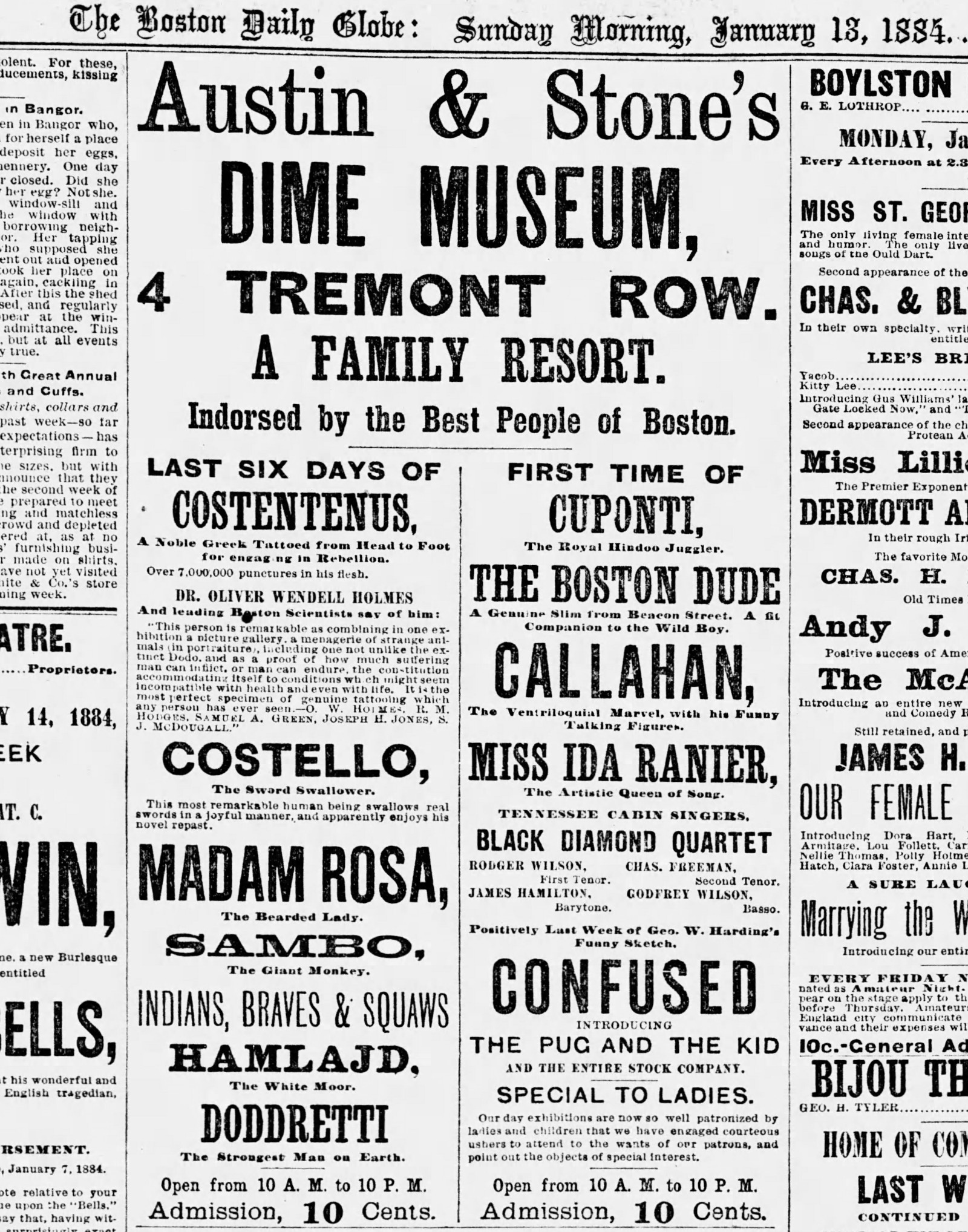

Austin & Stone’s Dime Museum Advertisement

Boston Daily Globe, 18 January 1884

Reproduction image courtesy of The Boston Globe

Note the billing for “Costentenus,” the world’s first widely- popular tattooed performer. He came to the United States in 1879, inspiring a generation of homegrown tattooed attractions, including Frank and Annie Howard.

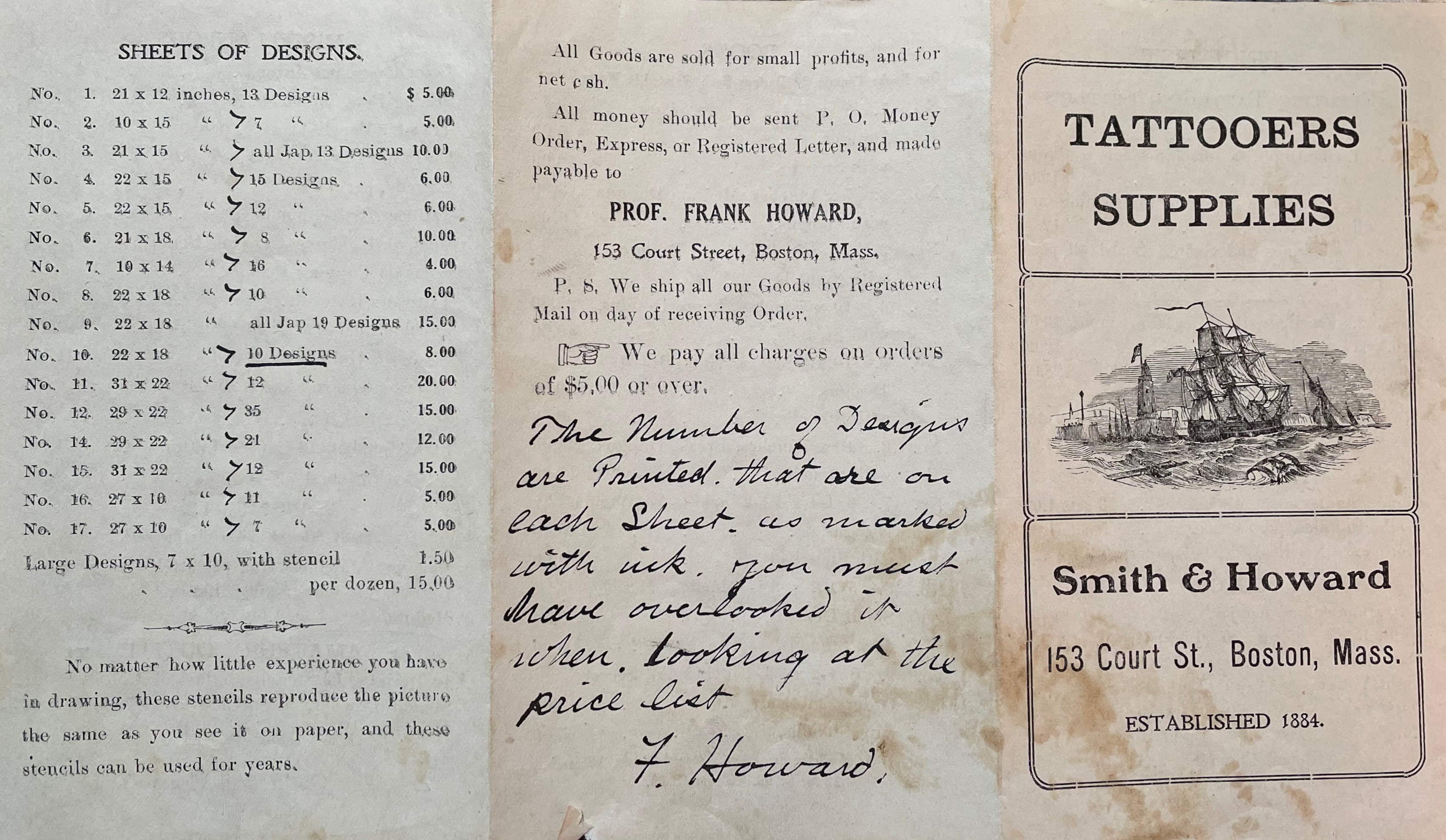

Prof. Frank Howard Promotional Biography and Tattoo Supplies List

Prof. Frank Howard Promotional Biography and Tattoo Supplies List E. Arnold, publisher London, c. 1898 Collection of Derin Bray

Scollay Square

Boston’s crowds of thrill-seekers got their kicks in Scollay Square, the city’s iconic entertainment district. Wedged between the Boston Port, Beacon Hill, and downtown, Scollay Square was also a major local and regional transportation hub. Here bankers and businessmen rubbed shoulders with store clerks, stevedores, sailors on shore leave, shoppers, stage performers, Harvard boys, daytrippers and travelers. Boston’s first tattooed performers joined the curiosities on display in Scollay Square’s many live theater venues, including Walker’s Nickelodeon and Austin & Stone’s Dime Museum.

Frank Howard Cabinet Card

Frank Howard Charles Eisenmann (1851–1927) New York City, 1885–90 Albumen silver print Collection of Historic New England

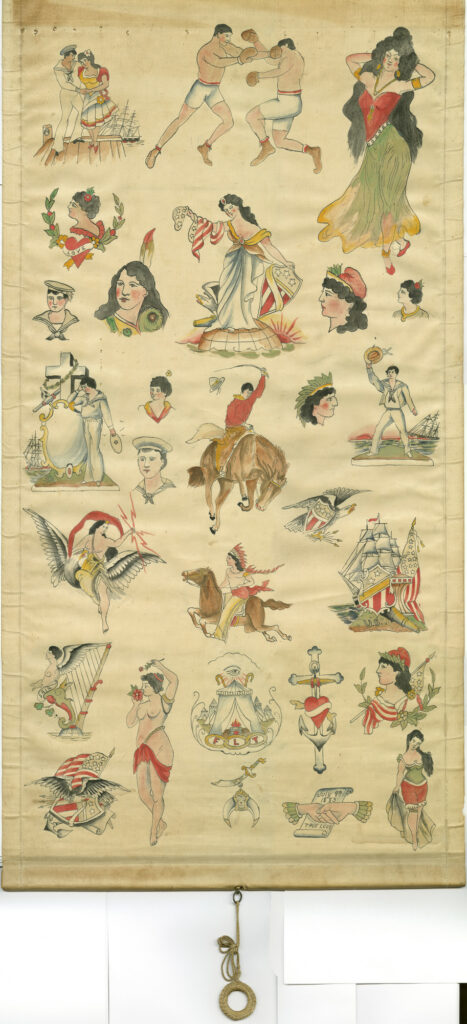

Frank Howard's Design Book

Look InsideThis early book of painted tattoo designs by Frank Howard features popular American imagery. Sentimental and patriotic designs like these permeated American culture, appearing on mass-produced ceramics, textiles, prints, and advertisements through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

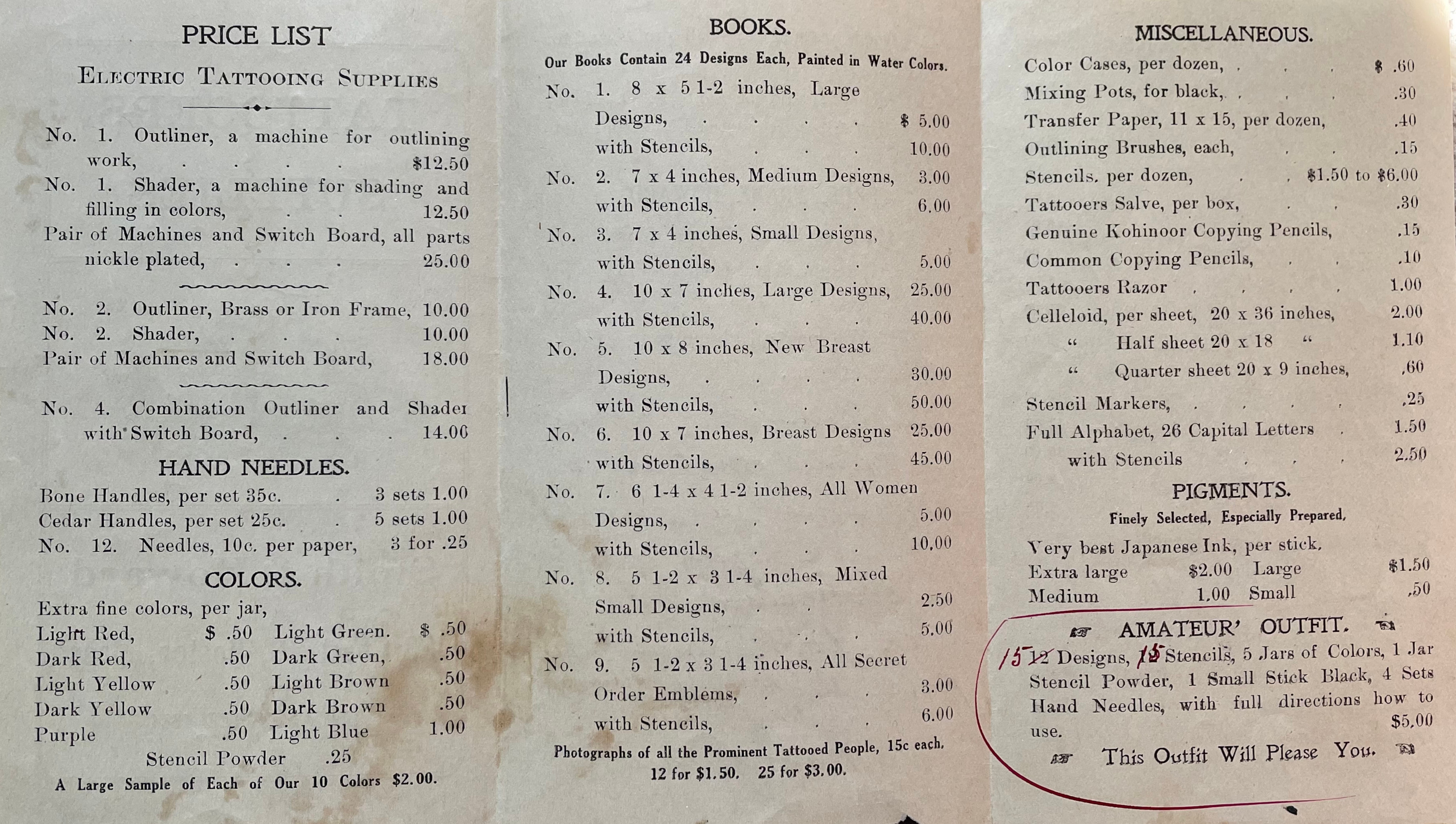

Smith & Howard

Between 1905 and 1911, Frank Howard partnered with fellow tattooer and machinist Ed Smith to establish Smith & Howard, a successful mail-order tattoo supply business. Ed likely built the tattoo machines they sold, while Frank was the face of the company, corresponding with and providing personalized service to customers.

Smith & Howard Tattoo Supplies Price List

Boston, c. 1910

Collection of Historic New England

![Directions To mix stick of Black Ink, which is always used for the outlines and shading in all designs. Put about 8 or 10 drops of pure cold water in a small dish, (the bottom of a cup or saucer turned upside down will do). Then rub one end of Black Stick around and around in the water in the dish until the water is very thick almost sticky, then it is ready to use. To pix all other colors and to get the best results, you should use (Pure Medicinal Alcohol). Pour in Color Jars and stir around until well mixed, have them medium thin just so colors will hold to the needles when you dip them in and lift out. To use Stencils, touch dry finger in dry Stencil Powder and rub lightly over the rough surface of pencil until all marks are filled up. Now wet skin where design ins to go and shave off all hairs, (shave down). Now lay stencil on skin and press a little, lift up and you will find outline of design. To Tattoo. Hold skin tight with left hand, pick up outlining needles with right hand, dip points in black ink and press lightly into skin, commencing at lower right hand corner and work up and across, following the lines, until all finished, then wash off and dry, look over the work and fix up all places skipped. Now put in all shading that is needed. Now put in the next darkest color that the design calls for, [and] so on until the design is all finished. Then wash off and dry and rub on a little Vaseline, and leave to heal up. Any more information you require at any time, write us and we will help you all we can. P.S. The largest [design] in this outfit, the Eagle and Shield is a sample of the designs in our $3.00 book of 24 designs, stencils to match $3.00 extra. P.S. Please write us as soon as you receive goods. Smith & Howard 153 Court St., Boston, Mass.](https://eustis.estate/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2022/05/1.24-Howard-Smith-tattoo-supplies-price-list-open-1.jpg)

Smith & Howard Tattooing Directions

Boston, c. 1910

Collection of Derin Bray

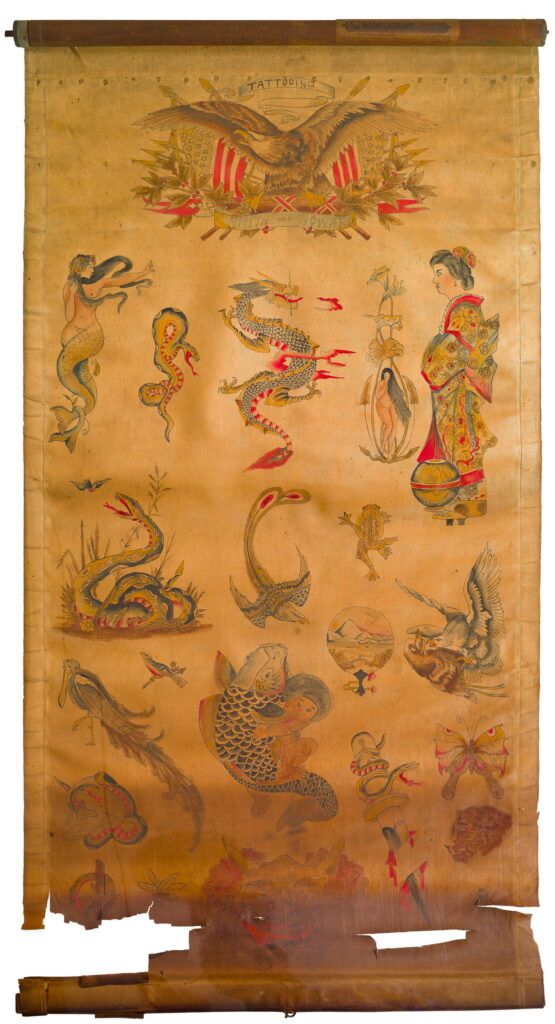

Flash Art Window Shades

The shops of early tattoo artists were often cramped, and tenancy could be brief. Painted window shades were hung on shop walls for clients to peruse, then simply rolled up and carried to new quarters when the tattooer moved on.

Window Shade with Painted “Smith & Howard” Eagle

Window Shade with Painted “Smith & Howard” Eagle

Frank Howard (1857–1925)

Boston, 1901–11

Reproduction image courtesy of Jared Hook

Between 1905 and 1911, Frank Howard partnered with fellow tattooer and machinist Ed Smith to establish Smith & Howard, a successful mail-order tattoo supply business. Ed likely built the tattoo machines they sold, while Frank was the face of the company, corresponding with and providing personalized service to customers.

Japanese Influence on Western Tattooing

America’s enthusiasm for Japanese tattoo designs grew out of the commercial and cultural interplay that flourished between Japan and the West after 1853, as Japan ended two centuries of isolationist foreign policy.

America’s enthusiasm for Japanese tattoo designs grew out of the commercial and cultural interplay that flourished between Japan and the West after 1853, as Japan ended two centuries of isolationist foreign policy.

Over the next several decades, Western merchant sailors and wealthy tourists flocked to the previously reclusive nation. The lush, dynamic, full-body compositions of traditional Japanese tattooing captivated Western travelers’ imaginations. Acquiring this spectacular body art—and undergoing the long, costly ordeal of being hand-tattooed by a Japanese master—became coveted status achievements for English nobles and British and American socialites of the late 19th century. Sailors also acquired Japanese tattoos while in port, and carried the new aesthetic home with them.

Japanese and Western tattoo artists swiftly adapted the traditional art form to the demands of Western popular culture: smaller, “souvenir” tattoos became the norm, and a static design repertory of dragons, geishas, animals, and flowers—largely detached from their original symbolism—replaced the heroic warriors, comic figures, and powerful gods that had so enriched traditional Japanese tattooing. By the 1890s, several Japanese tattoo artists had set up shops in Europe, Great Britain, America, and Australia, and American tattooers were offering the “latest in European and Japanese designs.”

“Japanese”-style tattoo designs remain in high demand today, as Western consumers continue to respond to their enduring mystique and special appeal.

Frank Howard Flash

Flash designs by Frank Howard (1857–1925) Boston, 1905–15 Ink and watercolor on paper Collection of Jared Hook

Tattoo Kit and Supplies Owned by Joseph Hallworth

Tattoo Kit and Supplies Owned by Joseph Hallworth

Probably Boston, c. 1907

Various materials

Collection of The Strong, Rochester, New York

Chelsea, Massachusetts, native Joseph Hallworth (1872–1956) is best remembered as the magician Kar-Mi. Hallworth and his wife, Catherine (1874–?), and children trouped throughout America, performing a variety of acts and death-defying stunts, including sword-swallowing, sharpshooting, and knife-throwing.

Between shows, Hallworth tattooed under the moniker Joe Van. His traveling tattoo kit includes a mail-order catalogue and business card from Smith & Howard, who likely supplied him with some of his equipment.

Tattoo Design Books, Stencils, and Equipment Owned by Joseph Hallworth

Tattoo Design Books, Stencils, and Equipment Owned by Joseph Hallworth

Probably Boston, c. 1907

Various materials

Collection of The Strong, Rochester, New York

Joseph Hallworth may have painted these tattoo designs from Frank Howard’s samples, possibly under Howard’s instruction. The tattoo machines were probably built and sold by Smith & Howard.