Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

Living and Working in the Mansion

Edith and W.E.C. Eustis lived on this estate with twin sons Gus and Fred and younger daughter Mary. Because of the size of the property, the family employed a full domestic staff in the mansion as well as a large staff to manage the grounds, greenhouse, and farm complex.

The Hall

A grand space at the center of the home

When the Eustis Estate was built in the late 1870s, the “living hall” was a relatively new concept. Architect William Ralph Emerson was a key proponent of this large and inviting space. He included the design feature in nearly all of his house plans. The living hall was more than just a space that connected rooms; it was a vital part of the house and a central part of daily life.

The living hall was also among the first impressions visitors had of the young couple’s home. Guests entered through the vestibule, where they encountered a pair of dramatic stained glass windows, colorful yet obscuring the view into the hall beyond. Once inside the hall, visitors were impressed by the imposing fireplace of molded terra cotta set behind an arch covered in gold leaf. The richly carved staircase soaring three stories anchored the other side of the room. Opposite the front doors, plants from the estate’s greenhouse thrived in the sunlight.

Historic Photo Gallery

Click on each image to take a closer lookThe Parlor

A warm and elegant gathering space

The large parlor was the main living room for the Eustis family and a space to receive and entertain guests. The intricately carved fireplace with windows on either side is the focal point of the room. The hearth is outfitted with a radiant heating system in the floor that warms the tiles from below. When Historic New England acquired the property, the walls of this room were white. Photographic evidence and microscopic paint analysis led to the discovery of the dramatic cloud-like wall treatment one layer beneath. A surprising restoration technique brought the walls back to their original appearance.

Historic Photo Gallery

Click on each image to take a closer lookThe Small Parlor

An intimate gathering space

The small parlor, as it was known to the family, hosted more intimate gatherings but could be opened to the large room next door when larger parties required it. The room centers on the moon-shaped fireplace, a decorative motif inspired by the fascination with the Far East during the 1870s and 1880s. This interest in Asia is found throughout the house, but no example is more lovely than the delicately painted bamboo branches that overhang the walls of this room. The John Gardner Low fireplace tiles, marketed in the 1880s as “Cobweb Frieze,” are another example of the interest in seeing beauty in nature.

The walls of this room retain their late twentieth-century paint treatment. Although this room has not undergone paint analysis, family history tells us that the band of decorative paint above the chair rail dates from the nineteenth century. The white walls were originally brown. Historic New England will restore the walls and ceiling of this room when funding allows.

Entertaining at the Estate

In the late 1870s Edith Eustis went from being a single young woman to a married mother of two overseeing the operation of a large household. While much of Edith’s life is still unknown, it is clear that she had a rich social life with many friends and family members in her circle. One of Edith’s childhood friends, Lois Curtis Low, kept a diary in which many entries involve young “Edie.” On March 27, 1869, Lois wrote about visiting Edith at her home when young “Willie” and a friend showed up to join the group. The diary later recounts Edith’s engagement to W.E.C., reporting that Edith was “radiant with bliss” when she told Lois of the news. After Edith and W.E.C.’s marriage, Lois noted the birth of the twins in 1877. In June 1879 Lois noted that she went to Milton to visit Edith at her new home:

“A long delightful visit in Boston, five weeks! …While in Boston I went out to Milton and saw Edith Eustis and her funny little twins and her magnificent house—none comparing. It is one of the finest I ever imagined.”

Domestic Staff at the Estate

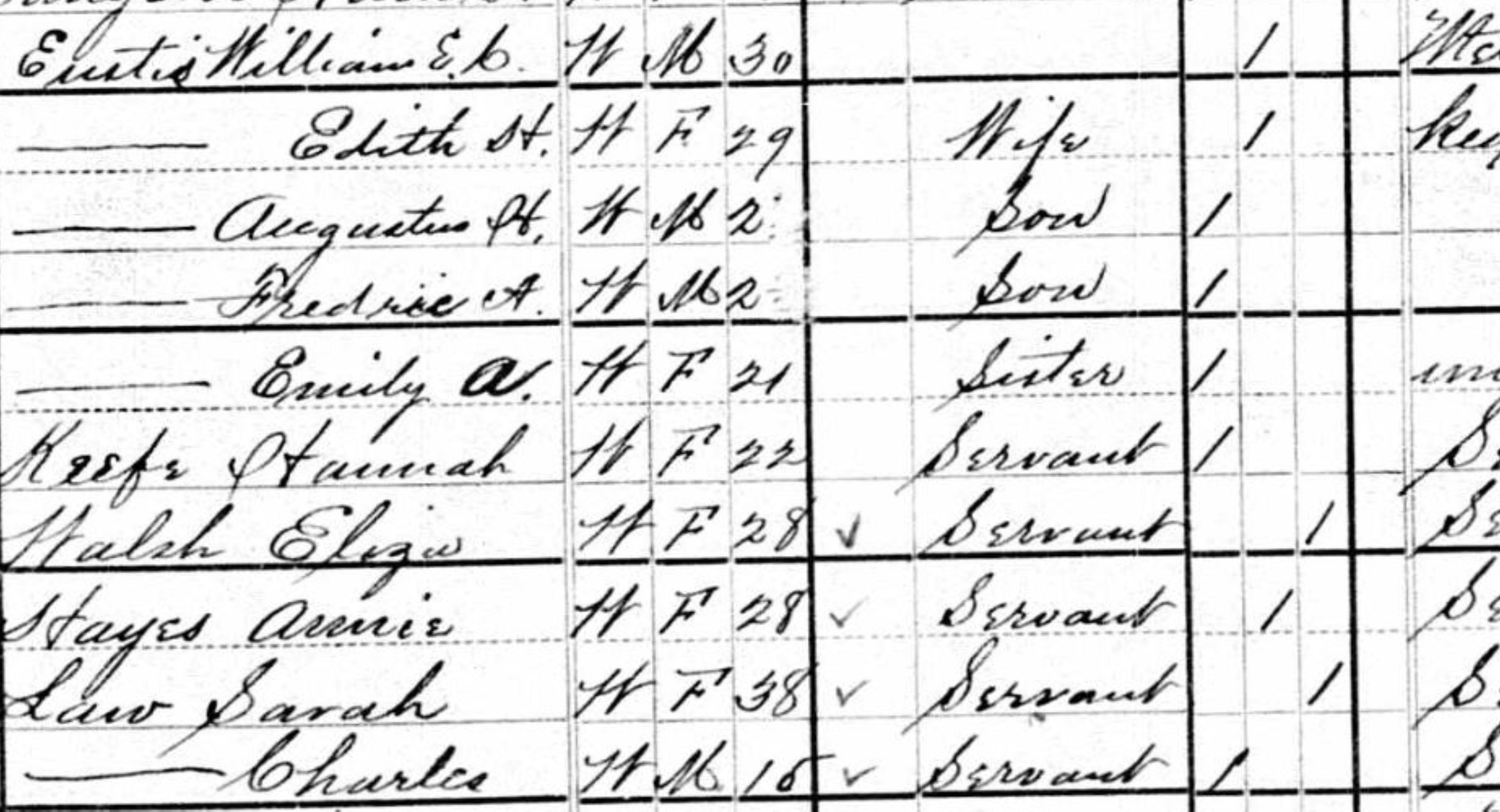

During the early years of the Eustis Estate, the domestic staff was entirely made up of people from outside the United States. In 1880 a woman from England worked and lived in the house, likely as the nurse who looked after the young twin boys. A young woman of Irish descent and three people from Canada, including a mother and son, comprised the house staff that year.

Although this room was clearly the domain of the Eustis family, it was attended to and cleaned by the domestic staff. A call button on the wall to the right of the double door summoned the parlor maid, who brought afternoon tea or whatever the family required. A strict cleaning schedule dictated how a house of this size was to be maintained, with specific activities on preassigned days. During the late 1800s most houses of this size were cleaned thoroughly once each week.

The Dining Room

A glittering and glowing room

The Eustis family ate all their meals in this room. Dinner required formal dress and consisted of defined courses, which was typical for wealthy families. The setting was more relaxed during breakfast and lunch. The food was served by a waitress, a term that refers to female servants who served meals in the dining room.

Family history also tells us that during the winter months the parlor was often too cold to spend time in and the family would use the warmer dining room as a sitting space.

Historic New England meticulously restored this room to its 1870s decorative scheme. Gold-colored paint applied to textured walls created a surface that glittered in the dancing light of the gas chandelier. The silver paint on the ceiling softly glowed. In the nineteenth century, this room dazzled guests while they dined.

Historic Photo Gallery

Click on each image to take a closer lookThe Kitchen

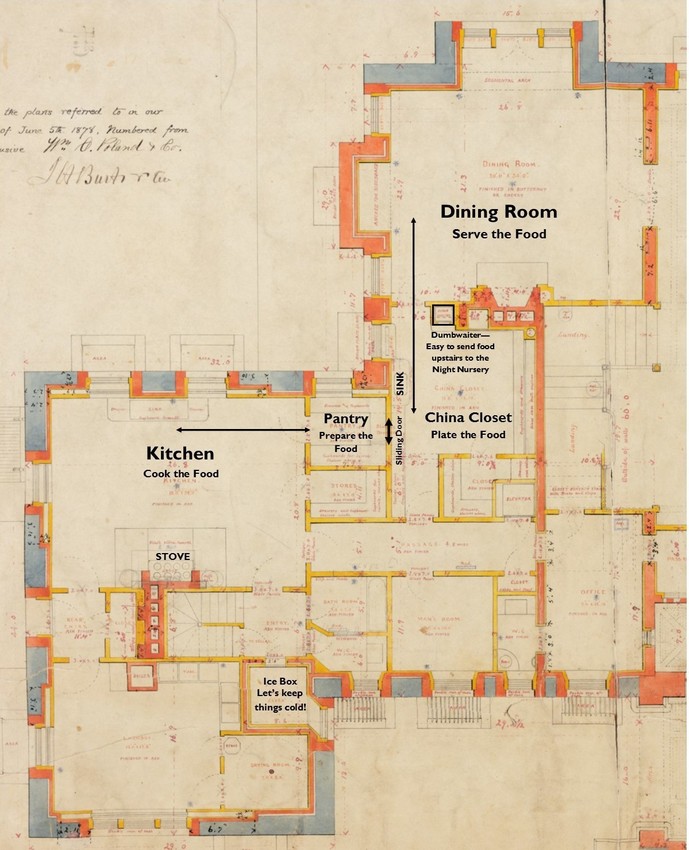

The service wing of the house was designed for practicality and to be carefully hidden from public view. Workflow was a priority in the service spaces, and the design reflects that. Many modern conveniences were installed that allowed the domestic staff to complete their daily tasks efficiently.

“The kitchen by first right is the cook’s domain. The butler’s pantry–so called–and the dining-room are the field of the waitress’s operations.”

From The Up-to-Date Waitress, 1908

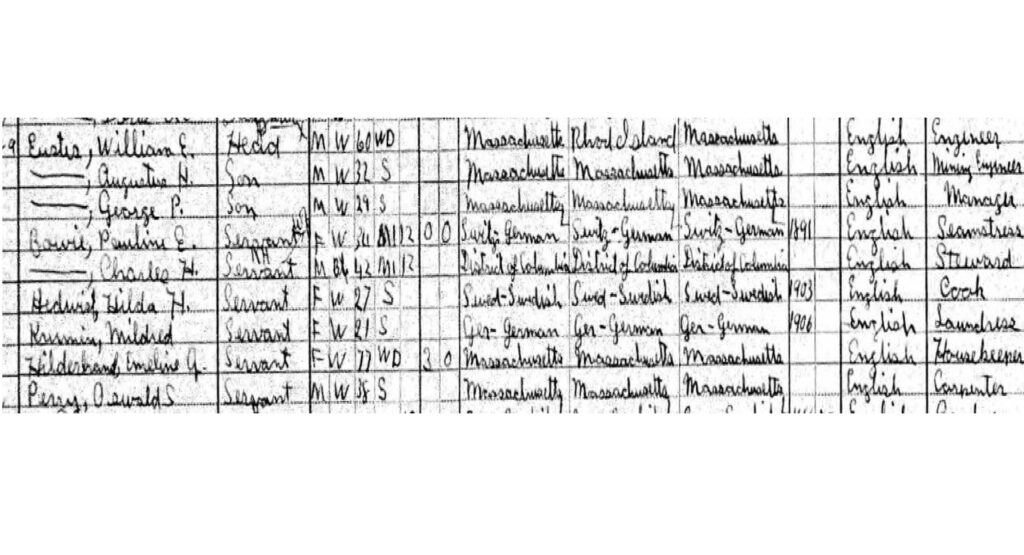

Domestic Staff

During the early years of the Eustis Estate, the domestic staff was entirely made up of people from outside the United States. In 1880 a woman from England worked and lived in the house, likely as the nurse who looked after the young twin boys. A young woman of Irish descent and three people from Canada, including a mother and son, comprised the house staff that year. In subsequent years the census shows more Americans in these positions, as well as domestic staff from Ireland, Switzerland, Germany, and Sweden.

The census data only represents those living inside the mansion house. (See the next section for the layout of their living quarters.) The family employed a butler who is not listed on the census, so he likely lived in another building on the property. There were at least a dozen other staff members (and their families) living and working on the estate, housed in the nine houses on the property maintained for employees. All staff were supplied with dairy products and produce from the gardens and orchards.

1880 Domestic Servants

The 1880 national census listed the following people as domestic servants who also lived in the mansion house. As the eldest person on staff it is likely that Sarah Law was the cook or head housekeeper.

Hannah Keefe, 22, Servant

Eliza Walsh, 28, Servant

Annie Stayes, 28, Servant

Sarah Law, 38, Servant

Charles Law, 15, Servant

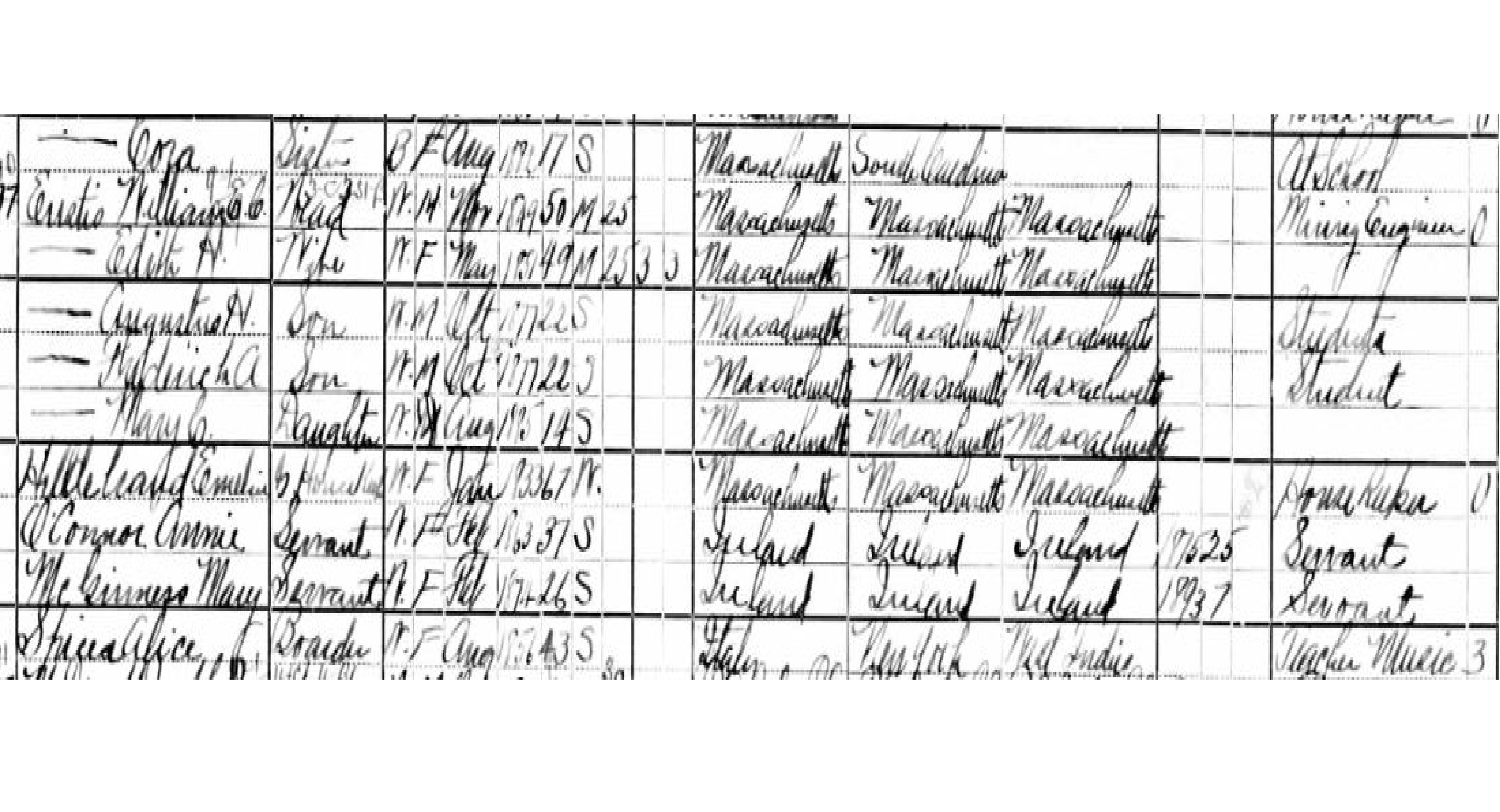

1900 Domestic Servants

The 1900 U.S. Census recorded more details about a person’s occupation. As a result, we know specifically that Emeline Hildebrand was the housekeeper and that Alice Spicer may have been Mary Eustis’s music teacher.

Emeline Hildebrand, 61, Housekeeper

Annie O’Connor, 37, Servant

Mary McGinness, 26, Servant

Alice Spicer, 43, Teacher Music

1910 Domestic Servants

By 1910 Emeline Hildebrand was still the head housekeeper and Hilda H. was the cook.

Pauline E. Bowie, 34, Seamstress

Charles H. Bowie, 42, Steward

Hilda Hedwig, 27, Cook

Mildred Krumin, 21, Laundress

Emeline A. Hildebrand, 77, Housekeeper

Oswald S. Perry, 38, Carpenter

Walker and Pratt Stove

This stove is dated 1879, which means that it was a brand new, top of the line item when it was installed here the same year. A large black iron hood was installed over the coal stove, the outline of which can still be seen in the bricks. Prior to the 1970s when radiators were installed this coal stove was the only source of heat in the kitchen.

On Speaking Tubes

Because this wing was tucked away far from the public spaces or family bedrooms, it was important for the family to be able to communicate with the domestic staff who lived and worked here. To accommodate this, speaking tubes were built into the walls of the house during construction, running from strategically chosen rooms down to the kitchen. There are six different speaking tubes:

1. Night Nursery

2. Second Floor Hallway

3. Third Floor Hallway

4. China Closet

5. Bed Chamber Dressing Room

6. Lab

In the rooms above, the opening of the speaking tube is a flared cone of ceramic. The other end has a whistle valve, so that if a person blows into one of the tubes in the house a whistle, like that of a tea kettle, will sound in the kitchen. This alerts the person on the other end as to which tube is in use and they can then open the valve and have a conversation.

“The habit of calling from the top to the bottom of the house is sometimes permitted when only one servant is kept. It should never be allowed…Speaking-tubes are most desirable, but when they are out of the question a bell can almost always be arranged which will notify the family of the arrival of visitors, or will serve to call the maid, if her presence is desired above stairs. American voices have sufficient reputation for loudness and shrillness already, without increasing these unpleasant tendencies by screaming orders up or down a couple of flights of stairs.”

From Housekeeping Made Easy, 1888

A Modern Call System

The Electric Annunciator

An electric call box system facilitated communication between the Eustises and their staff. A family member would push a wall-mounted button in one of twenty spaces throughout the house, causing the bell at the top of the call box to ring and the specific room that was calling to be indicated. Depending on the room, a parlor maid, chamber maid, waitress, or other staff member would attend to the family member calling.

The Second Floor Hall

The concept of the open hall continues to the second floor, providing views from the first to the third floor. The Asian-inspired moon window is the central feature of the second-floor hall. It frames a sweeping view down a line of trees leading away from the house. The massive beech tree can be seen as a sapling in nineteenth-century photographs. Heavy portiere curtains can be pulled across the alcove to keep out cold air.

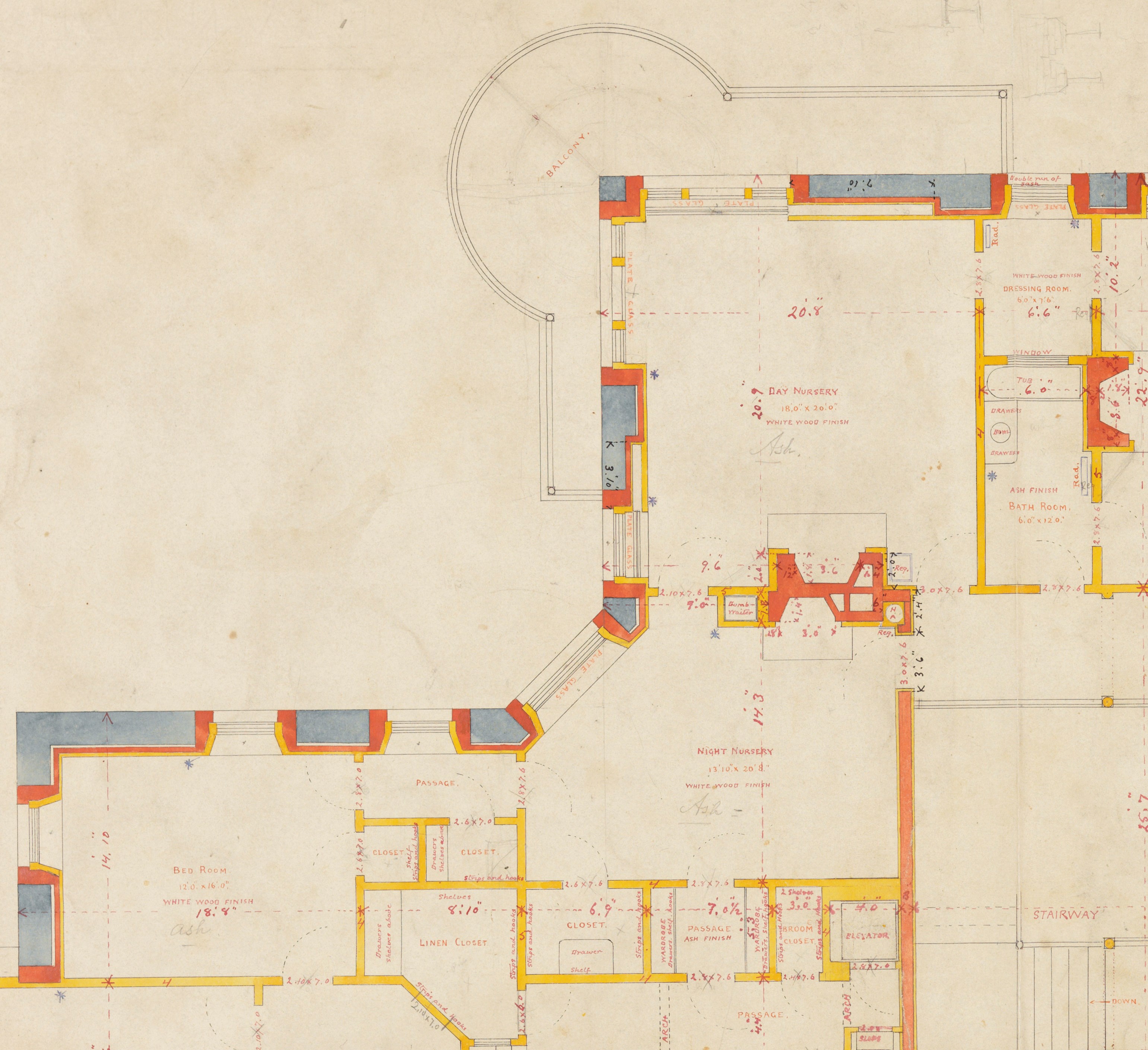

The second-floor hall provided access to four bedrooms, a library, day nursery, and night nursery. Although the principal bed chamber and night nursery both had easy access to bathrooms, only one toilet was located on this floor, tucked away just past the doorway to the right of the moon window. Today, four of the rooms on this floor are used as changing exhibition galleries. The library continues to serve its original use as a place to read, explore, and relax.

The Library

The man cave

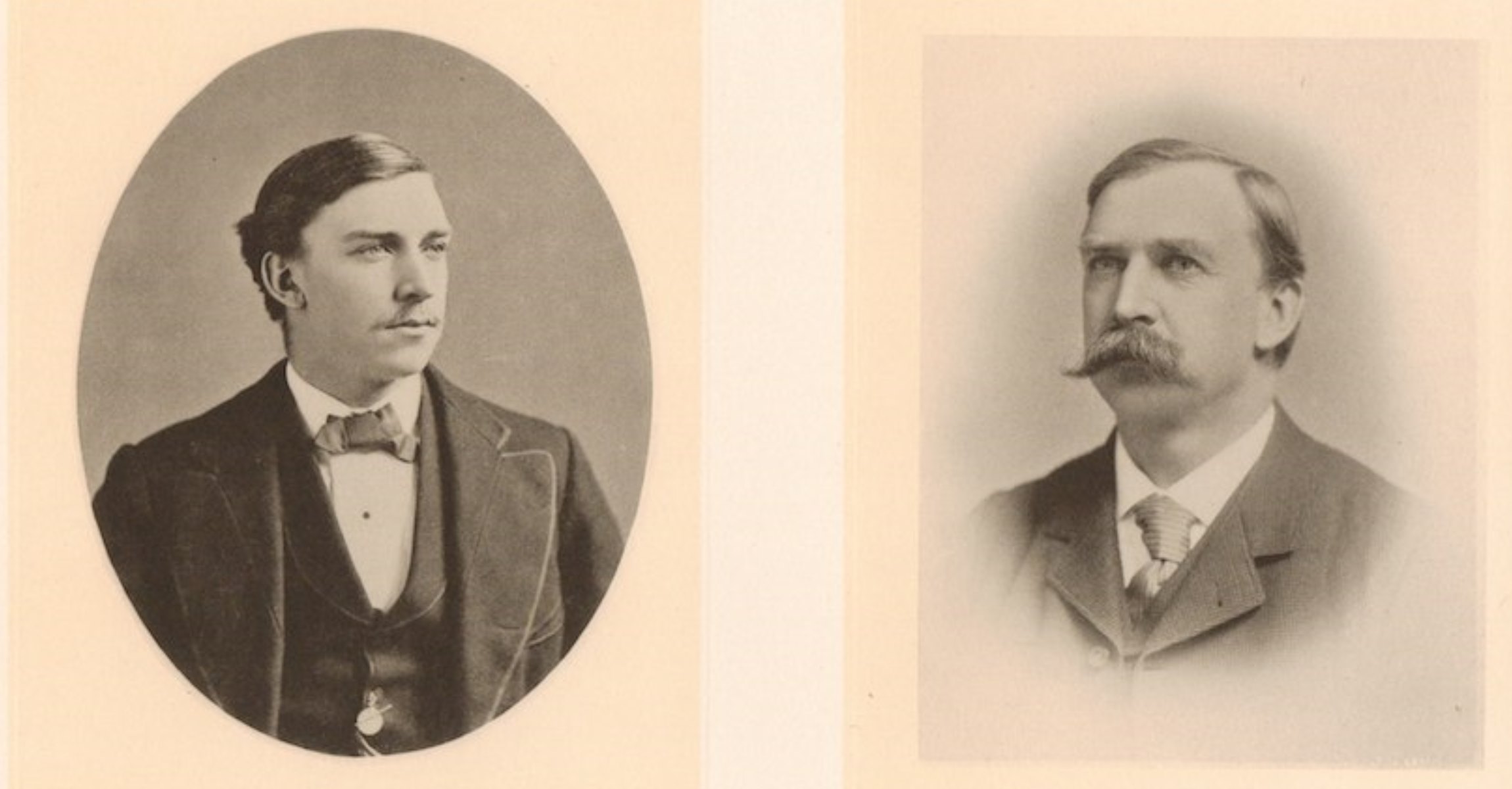

The library, perched over the porte cochère, was the private space of W.E.C. Eustis. It housed a large collection of books and souvenirs from his travels and served as his home office, where he managed his personal affairs.

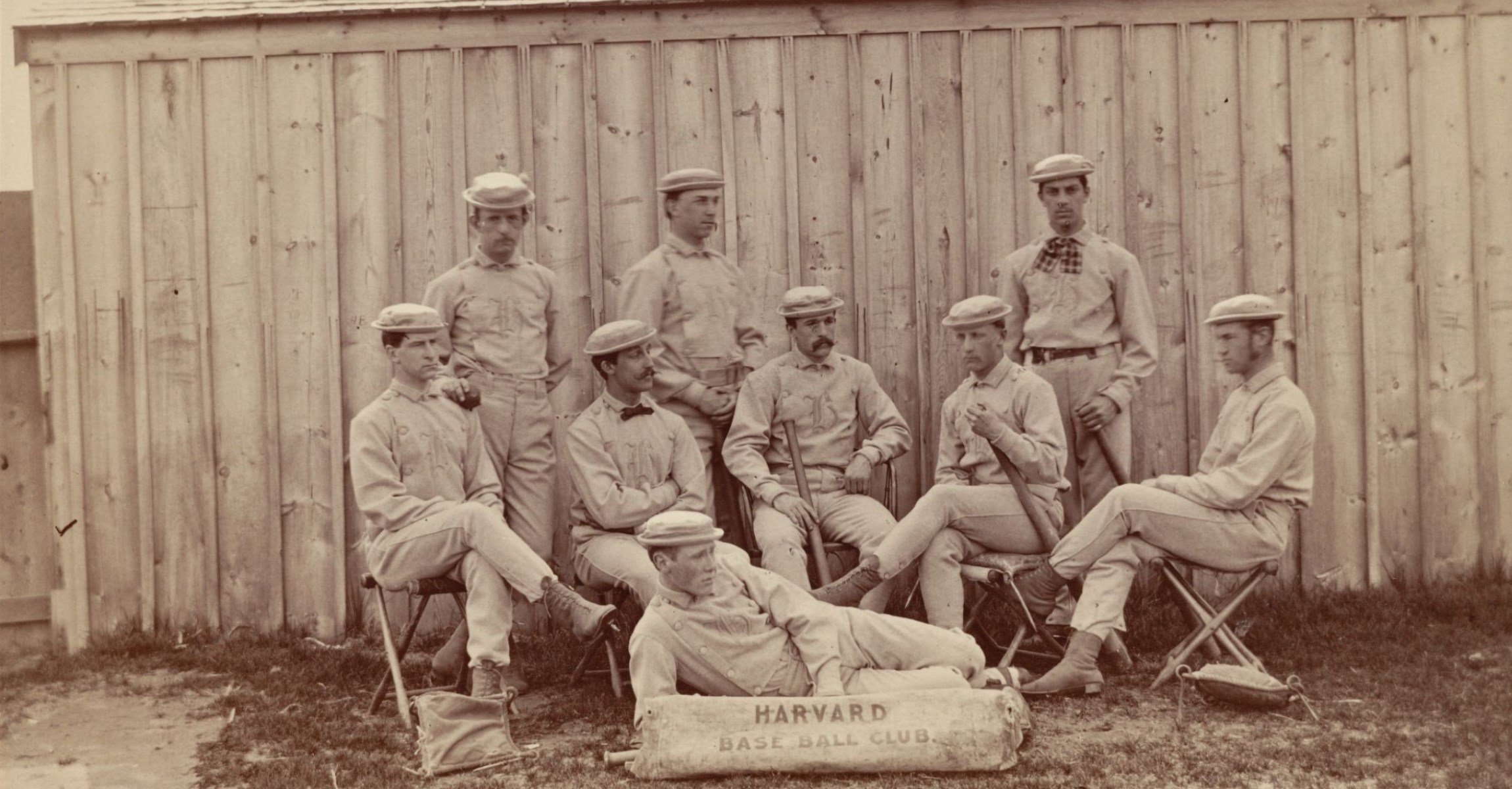

W.E.C. graduated from Harvard University with a Bachelor of Arts in 1871. He completed a second degree in science two years later. While in school, Eustis was a member of the Harvard Nines baseball team and played a total of 101 games during his time there.

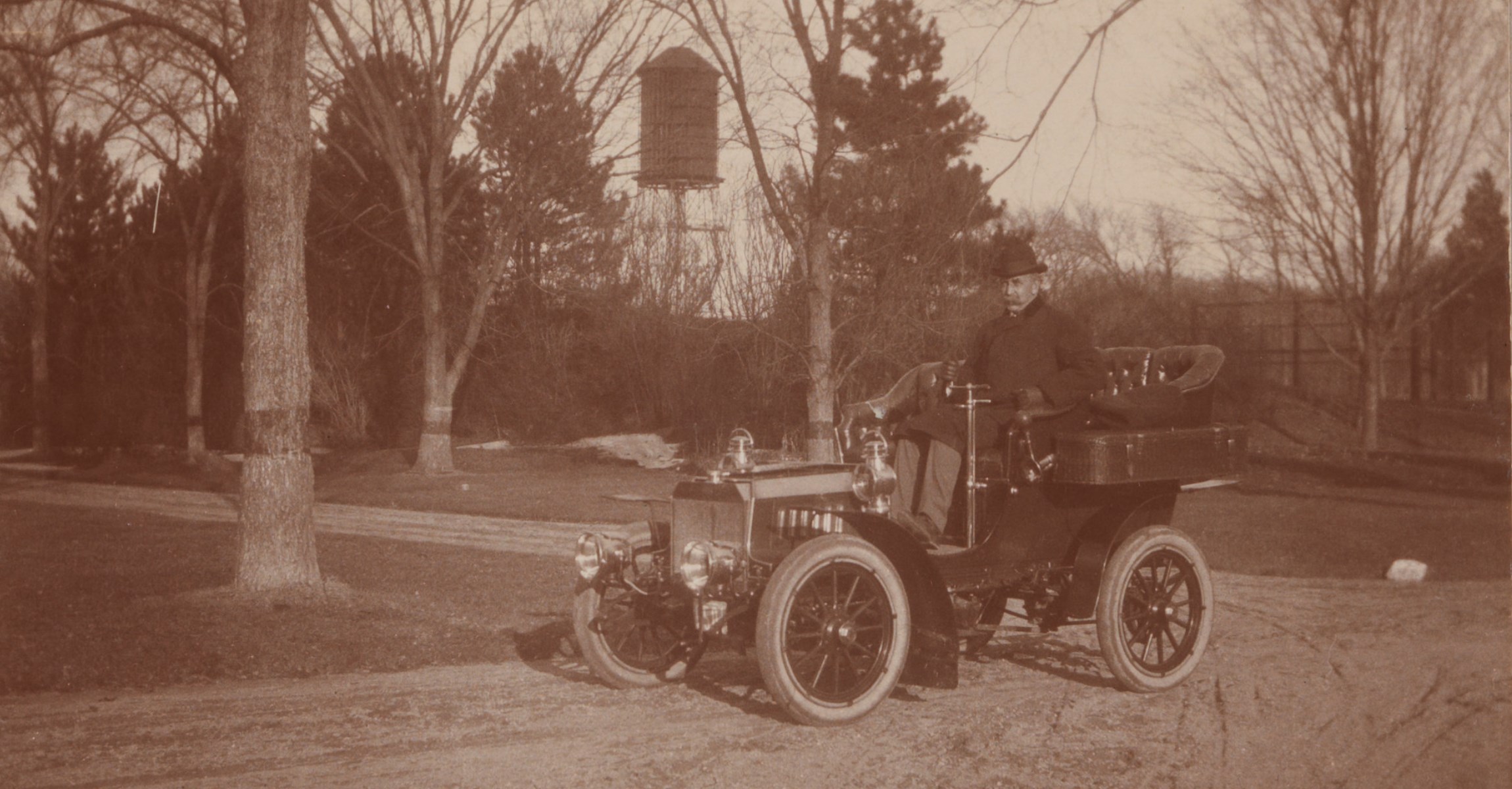

W.E.C. Eustis was listed as a “metallurgical engineer” in the 1880 U.S. Census. He found great success in his work as an engineer and owned three companies across North America: Eustis Mining Company in Quebec, Melones Mining Company in California, and the Virginia Smelting Company in Virginia. He also patented several chemical metallurgy and mechanical inventions.

His interests and pursuits in engineering and technology migrated into his personal life, as well. A staircase hidden behind the velvet curtain in this room leads to a third-floor room he called his “laboratory,” which once housed his “tinkering room” where he worked on devices such as radios and other new technology.

W.E.C. was also an avid photographer and had a dark room in the basement. Many of the historic photos seen here are from the glass plate negatives that he took during the 1880s and 1890s.

An avid yachtsman

sailing near Cape CodAn avid yachtsman

W.E.C. was an avid yachtsman who enjoyed sailing near Cape Cod. In 1894 Edith paid to have a summer home built in Cataumet, overlooking Buzzard’s Bay. In the Summer Social Register of 1919 W.E.C. Eustis was listed as the owner of three vessels, the Smelt, the Squid, and the Vega. In the winter months he traveled to the Canaveral Club in Florida where he hunted and fished. Several of his trophy animals were displayed in the Milton house, including a large sailfish in the library and a blue heron that was placed on the staircase overlooking the first floor hall.

A Working Estate

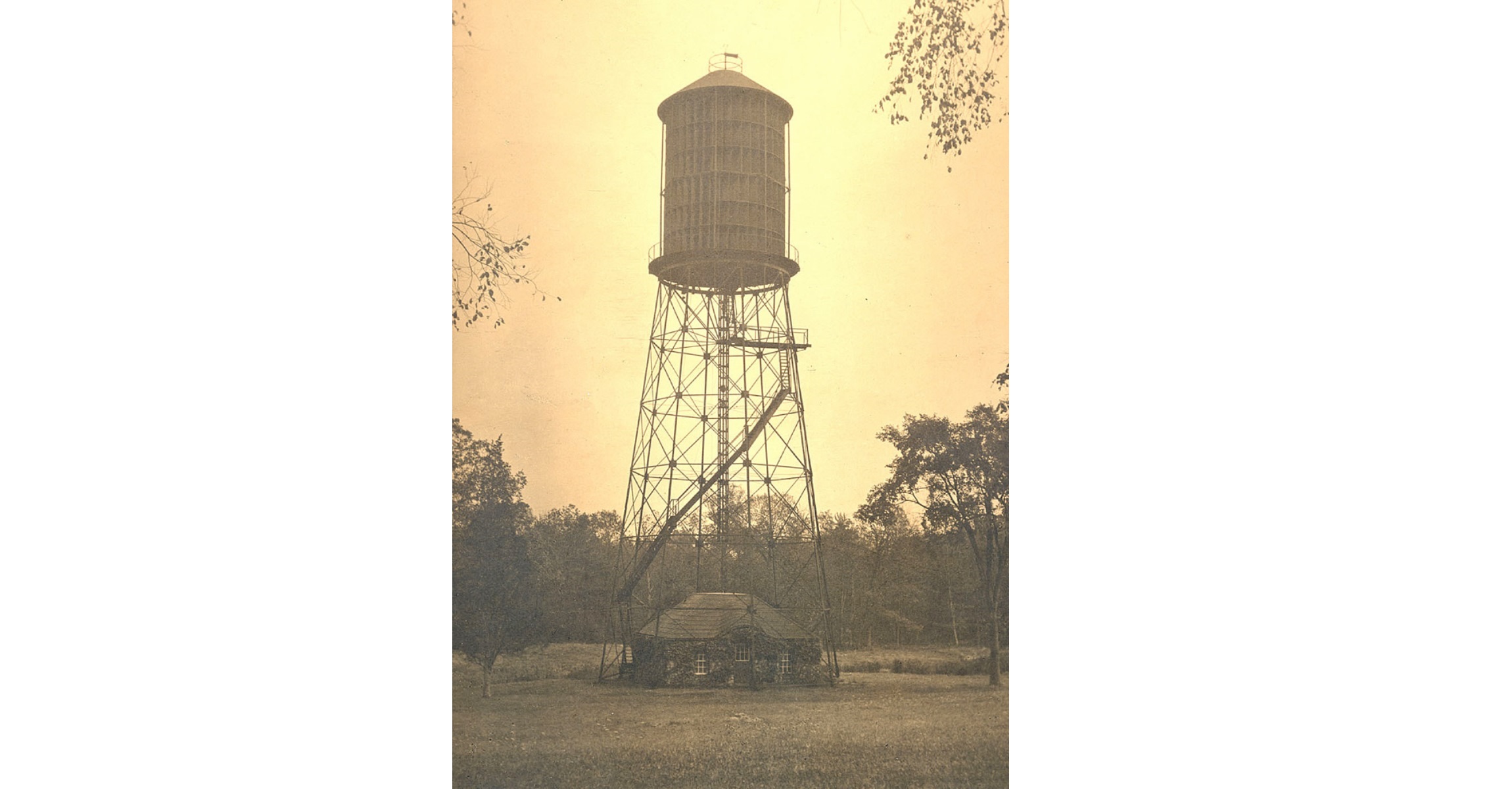

Aside from his professional work and personal hobbies, W.E.C. Eustis was interested in managing his Milton estate as a working farm. Most of the open land was cultivated, tended by a farm manager and a staff of gardeners and laborers. A large greenhouse was built on the property in the early 1890s and the boiler house behind it still stands.

The Eustises also created a small pond so that ice could be harvested during the winter. A wooden structure was built along the shore of the pond where ice could be stored.

In 1902 W.E.C. built a fieldstone power house near the pond. One hundred seventy-five feet above it stood a large wind turbine that powered a generator inside. This electricity was first wired to the library and eventually to the rest of the house. According to family lore, even after the entire house was connected to municipal power, W.E.C. kept the library hooked up to the on-site power source, which he believed to be more reliable. As a result, the library never lost electricity when the rest of the main house did.

Swedish immigrant Manning Johnson worked as the landscape gardener on the estate from 1904-1917. One of his many responsibilities was to maintain the windmill and power system. His son Paul grew up on the estate and loved to follow his dad as he worked:

He would check [the windmill] twice a day to change instrument charts and to see that everything was working fine. The wind would usually handle the generating of electricity and the pumping of water, but in calm weather, Dad would start the huge gas engine to supplement the wind…The engine could be heard half a mile away. The mill would pump water and charge the batteries in the basement of the big house. At one time, it supplied the electricity needed for all purposes. (One Man’s Story, by Paul Johnson, 1991)

Historic Photo Gallery

The LibraryBed Chamber

This suite of three rooms (chamber, bath room, and dressing room) was used by W.E.C. and Edith Eustis. The bath room contains a tinned-copper tub, marble sink, and double set of storage drawers.

The dressing room contains an additional sink and provides light into the bathroom through an interior window.

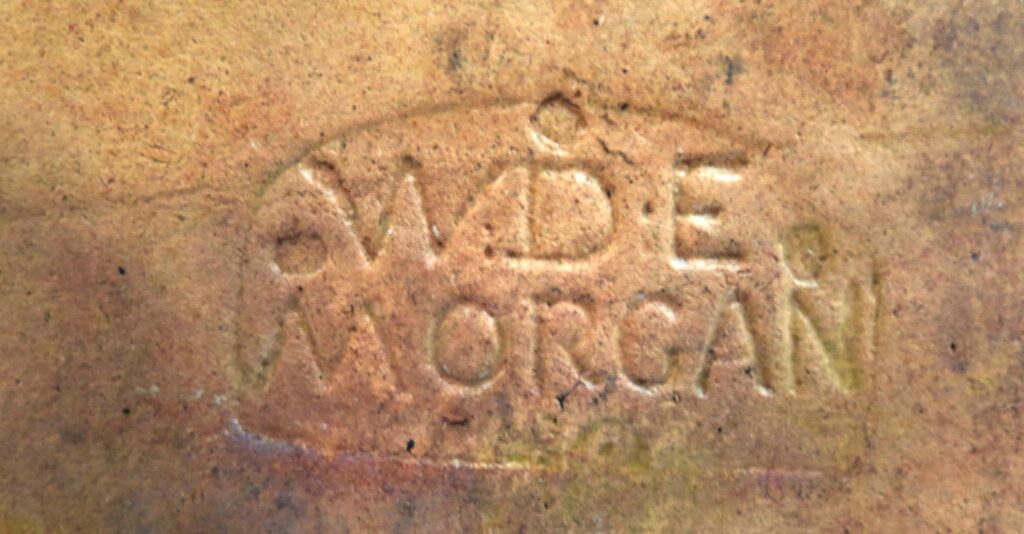

The bed chamber is dominated by a decorative mantelpiece with paneled corner wardrobes. The carvings on this elaborate fireplace surround are among the finest in the house. It features a pair of decorative tiles by William De Morgan, a high-end producer of art tiles and ceramics during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Three unused, identical tiles of this design were found in the basement, allowing us to identify them based on the maker’s stamp on the back. This particular mark dates the tile to 1872-1881 during the Chelsea period of De Morgan’s firm.

The Nurseries

When Edith and W.E.C. Eustis moved into their new home, their twin sons Fred and Gus were just two years old. The family employed a nurse to help care for the children. The day nursery, connected to the principal bed chamber via the dressing room, features a huge corner window providing wonderful views toward the Blue Hills. The capacious balcony allowed for the children to get fresh air without having to go downstairs.

Pictured, left to right: Edith Eustis, John Jeffries (son of W.E.C.’s sister), unknown woman (possibly Emily Eustis Jeffries), and Mary Eustis.

The children slept in the night nursery until they were old enough to move into private rooms on the third floor. A dumbwaiter originating in the china closet ran directly to this room, bringing meals upstairs for the children before they were allowed in the dining room. A bathroom was installed nearby for convenience. The nurse’s room, one of four servant bedrooms on this floor, was connected to the night nursery by a private passageway (seen in the bottom left of the image below).