Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

William Ralph Emerson Architectural Database > Literary

W. Ralph Emerson: The Architect as Reader and Writer

“Mrs. Palmer and Harriet came to dine with Mr. Emerson who came over from Winthrop for the purpose. I took him to walk and we drove him to Lynn in the afternoon. He afterwards sent me several funny notes (one written with the left hand, and every other line written backwards!)…”

-Sarah Gooll Putnam, August 13, 1884

Though his efforts as a poet and writer were overshadowed by other members of his family, William Ralph Emerson was an active participant in Boston’s late nineteenth-century literary circles. Spending time with his uncle, George B. Emerson, W. Ralph Emerson and his brother, Lincoln, were both introduced to the Boston Athenæum from a young age. Members of the Emerson family had been involved in the founding of the Athenæum which, in addition to being a library, had extensive art and sculpture collections.

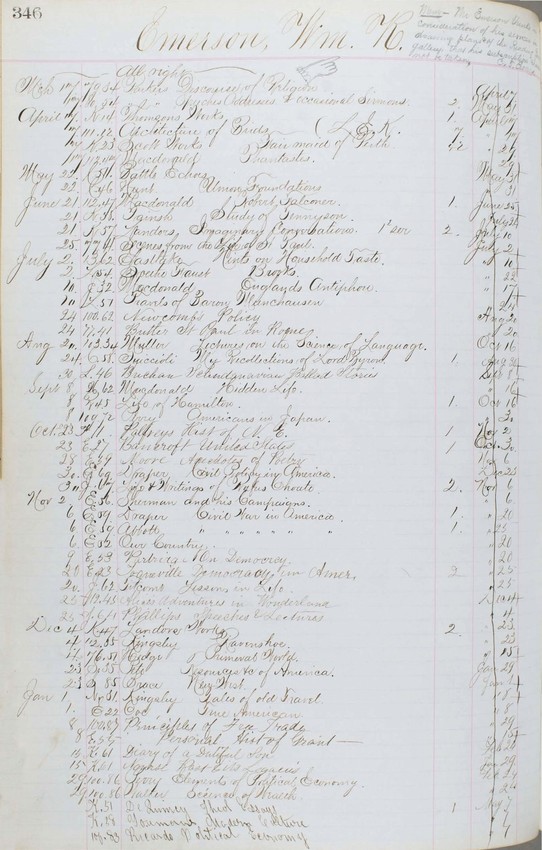

When Lincoln Emerson died in 1863, his Athenæum share was taken over by his brother. Circulation records show that W. Ralph Emerson was a voracious reader of popular titles, books on history, architecture, poetry, and more. Interested in current events, Emerson read Josiah Holland’s Life of Abraham Lincoln in 1866, the year it was published, in addition to books on garden architecture, Snow-Bound by John Greenleaf Whittier, works by Anthony Trollope, and others. His summer reading for 1869 included Goethe’s Faust, Edward C. Tainsh’s A Study of the Worlds of Alfred Tennyson, and Charles Eastlake’s newly-published Hints on Household Taste.

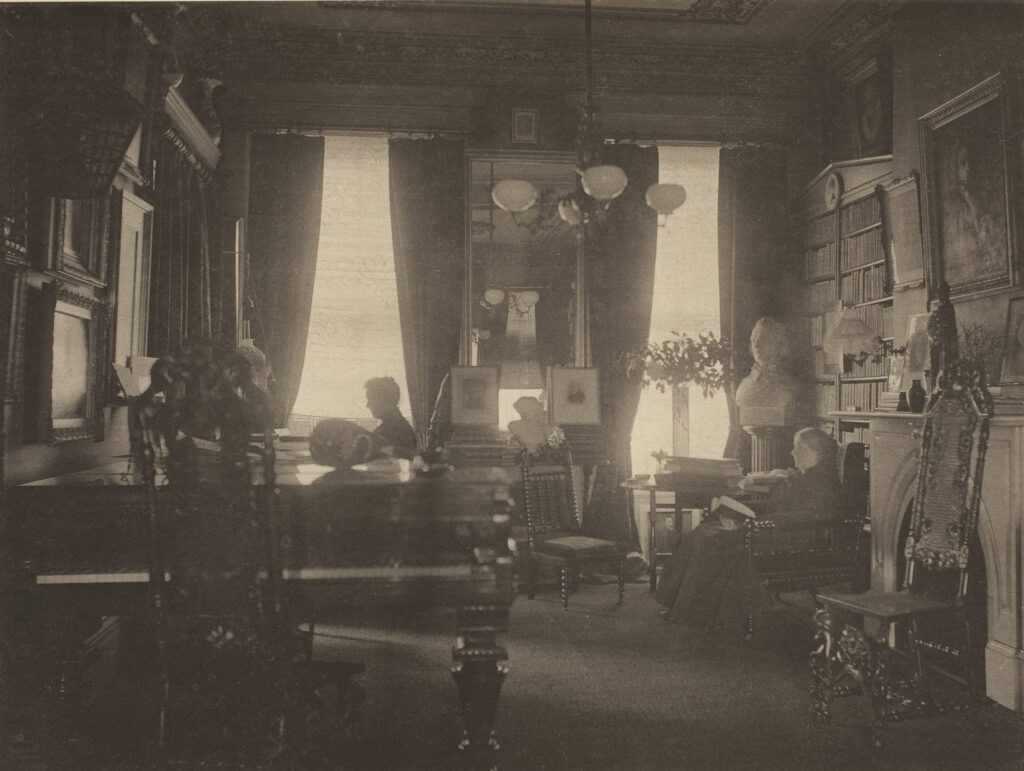

Emerson was close with members of Boston’s literary scene including Annie Fields, who attended the school operated by his uncle. A writer, and poet, and longtime partner of Sarah Orne Jewett, Annie Fields was known for her “little suppers + salons + soirées,” Sylvia Emerson wrote to a friend. The Emersons often moved to Boston in the winter months, and over the winter of 1897-98 they rented a house next Mrs. Fields. “She is an old friend of Ralph’s+ I know as our next door neighbor… will do a great deal to make our winter pleasant,” Sylvia noted.

As an architect Emerson worked for prominent writers including William James and Thomas Baily Aldrich. Aldrich became a close friend, and two Emerson pastels were included in a 1907 book of his writings. Inviting the novelist to dinner in 1891, Emerson described the evening he planned: “no dress coat, no especial manners, no temperance in eating, drinking + smoking.”

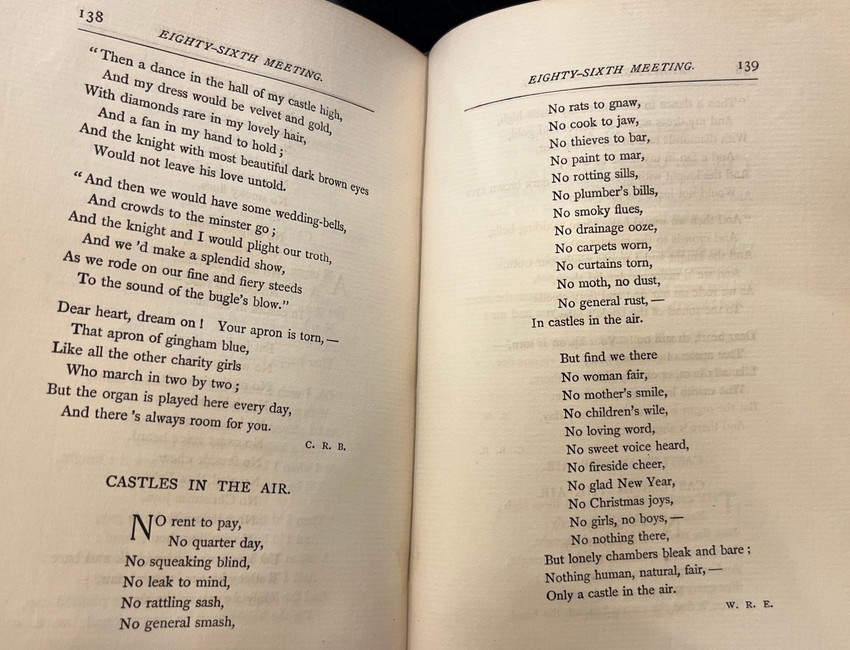

Beyond his social and professional ties with prominent literary figures, W. Ralph Emerson was an accomplished poet and published writer. In 1871 he published a one-act play, Putkins: Heir to Castles in the Air, about John Putkins, a census-taker.

In 1902 Emerson wrote an introduction for The Architecture and Furniture of the Spanish Colonies. Most architects were familiar with the architecture of Europe, but the buildings of Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Manila were not as well known. The beauty and richness of these places has come “as an almost unexpected revelation,” Emerson wrote.

Emerson was also a prolific poet. Boston newspapers published his1863 poem “Shadow Dance,” about the actress Maggie Mitchell, then performing at the Howard Athenæum. Despite being credited to “W.R.E.” the poem was incorrectly attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson when it was printed outside New England. Receiving congratulations for the poem, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote “I have no claim whatever to the graceful verses called ‘The Shadow Dance’ … I am too little a playgoer that I have never seen the artist in whose praise they were written. I believe the author is Mr. William Ralph Emerson, a young architect of Boston, and a man of worth and talent.”

The majority of Emerson’s poetry was unpublished and was likely unknown beyond his social groups. Sarah Gooll Putnam, an artist friend, recorded several of his poems in her journals, hearing them directly from Emerson or having received them in notes. With his quick wit and ability to compose on-the-spot, Emerson was invited to be a member of The Game Club. Arriving at meetings, members received a slip of paper with a subject upon which they had to compose a poem. As soon as the first poem was finished, the process was repeated so two poems were written before dinner, when they were shared.

Topics ranged from seasons, to travels, to even fellow members, and certain poems were selected for publication. Privately printed, The Verses of the Game Club were retained by members and their families. Sylvia W. Emerson’s set of five volumes exists today in the collection of the Boston Athenæum.