Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

William Ralph Emerson Architectural Database > Lectures

W. Ralph Emerson’s Lecture Circuit

“But among those few lecturers worth hearing, though not so well known as many now careening about the country, is Mr. W. Ralph Emerson – kinsman of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and aside from the reflection of his distinguished name [is] a man refined, elegant and talented in his writings, and who has the real genuine ring of humor. I have heard him lecture twice, and can only say if you would be entertained in a refreshing manner go and hear “The Discoverers,” should fate in the shape of a lecture committee ever take him eastward.”

-Jay, “Letter from Boston,” The Republican Journal, Belfast, Maine, November 7, 1872

Despite his primary occupation as an architect, William Ralph Emerson maintained a busy schedule giving talks and lecturing as well. Starting as early as 1856, Emerson’s public speaking engagements began attracting the attention of newspapers in the greater Boston area. With topics including politics, war, architecture, and predictions for the future, Emerson’s career as a public speaker lasted five decades and included talks throughout the northeast.

Gaining popularity in the mid-nineteenth century New England’s lyceum movement—an effort to provide adult education through lectures—provided Emerson with ready and appreciative audiences. In Boston he became friendly with Edward Everett, a major promoter of lecture-courses programs. Recalling in his eulogy Everett’s efforts to help the citizens of Boston, Charles Slack drew particular attention to “those charming lectures of Mr. Emerson, all of which are the direct benefit of Mr. Everett’s desire to instruct and benefit the community.”

W. Ralph Emerson realized the potential to profit from his skills as a public speaker, and in 1869 he wrote to have his name added to list of speakers promoted by James Redpath’s Boston Lyceum Bureau. Representing Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Julia Ward Howe, Mark Twain, and others, Redpath began his service the previous year, and Emerson was eager to market his speaking talents as well: “My subjects are ‘American Traits’, ‘The Coming Age and the Coming Man’, and ‘Popular Art’” he wrote.

In “American Traits of Peace & War” Emerson compared the United States, then approaching its centennial, with older and more established countries, while “The Coming Age and the Coming Man” offered the architect’s predictions for the future. “The Great Discoverers” and “Three Famous Men” considered those whose efforts led to great increases in knowledge. Beyond expected figures such as Christopher Columbus and the Norsemen, Emerson’s discussion included scientists, inventors, and physicists like Benjamin Franklin, Charles Goodyear, and Sir Benjamin Thomas. In addition to educational lectures, Emerson became a popular choice for Decoration Day (later renamed Memorial Day), and spoke before audiences in Marblehead, Cambridge, Lawrence, and Quincy, among other places.

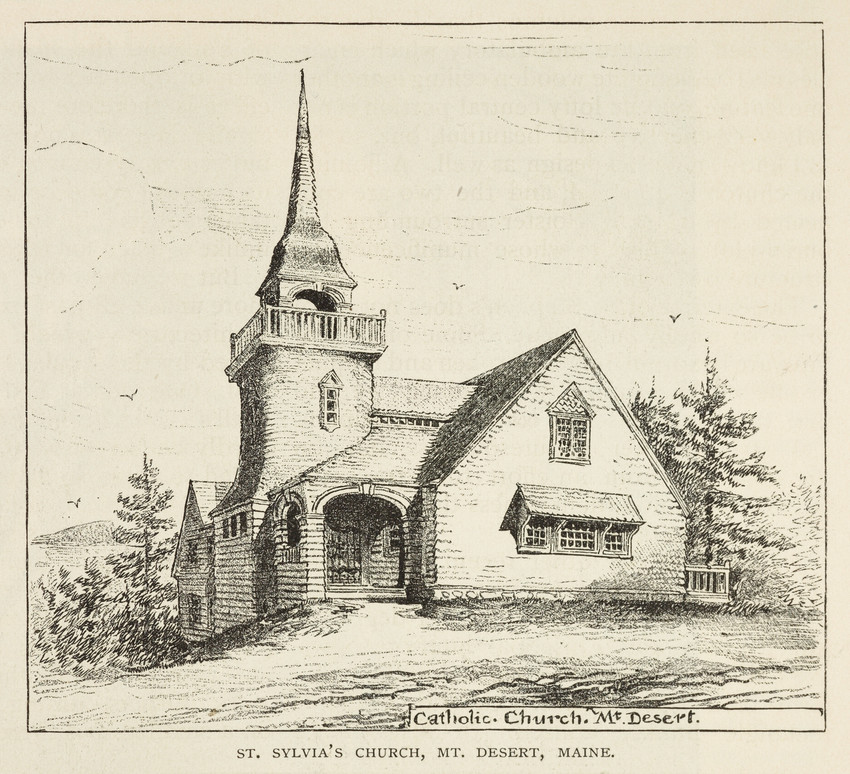

Not surprisingly many of Emerson’s talks focused on architecture, and with a sincere interest in older buildings he often addressed topics of architectural history and design. In “The Mechanic of 1775 and The Mechanic of 1875” Emerson extolled the virtues of earlier architects, builders, and designs. He lamented the destruction of Boston’s Hancock House and “condemned the shams of modern times,” such as nails made to look like screws and other facets of contemporary buildings and construction. To accompany a speech before the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic’s Association, Emerson wrote a song championing the skills of building professionals, sung to the tune of Auld Lang Syne.

What builds a Nation’s pillars high,

And its foundation strong?

What makes it might to defy

The foes that round it throng?

It is not Gold! Its kingdoms grand

Go down in battle’s shock!

Its shafts are laid on sinking sand,

Not on abiding rock.

Is it the Sword? Ask the red dust

Of empires passed away;

The blood has turned their stones to rust,

Their glory to decay.

And is it Pride? Ah! That bright crown

Has seemed to nations sweet;

But God has struck its lustre down

In ashes at his feet.

Not Gold; but only men can make

A people great and strong;

Men who for Truth and Honor’s sake

Stand fast and suffer long.

Brave men who work while others sleep;

Who dare while others fly;

They build a Nation’s pillars deep,

And lift them to the sky!

(Published in the Boston Daily Advertiser, September 8, 1875)

Older buildings fascinated the architect, frequently serving as inspiration for his own designs, and led to discussions surrounding topics of historic preservation. In “The Vanishing Landmarks of the Revolution” Emerson celebrated the historic buildings of cities such as Boston and Philadelphia, where older buildings were being destroyed and replaced. Speaking before Boston’s Beacon Club, he “made a plea for the preservation of old-fashioned houses,” claiming that “by and by we should get through floundering about in gingerbread architecture, and will then see a revival of the good old substantial colonial architecture.”

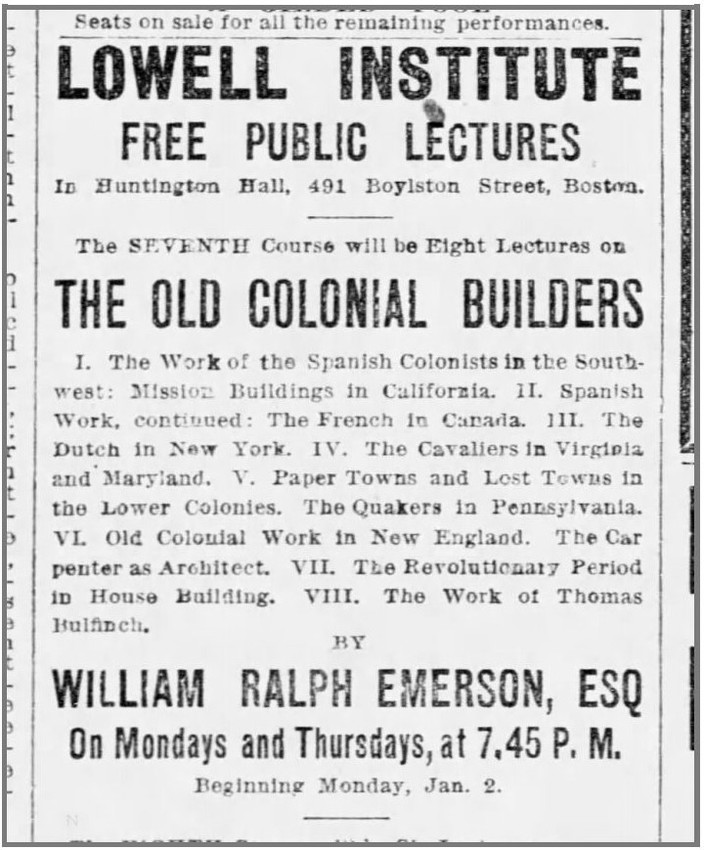

Eager to share his knowledge and views with larger audiences, Emerson developed an eight-lecture series for Boston’s Lowell Institute. Combining discussions of architecture with those of colonial expansion, economics, and history, the series considered a variety of themes. But it also allowed him to openly critique present-day conditions. While discussing legacy of Charles Bulfinch, among the earliest professional architects in the United States, Emerson criticized newer buildings, like those recently-constructed by Harvard College. If “they should be replaced by others of the same pattern as those of Bulfinch, even the architects would be glad to see them remodelled,” he argued.

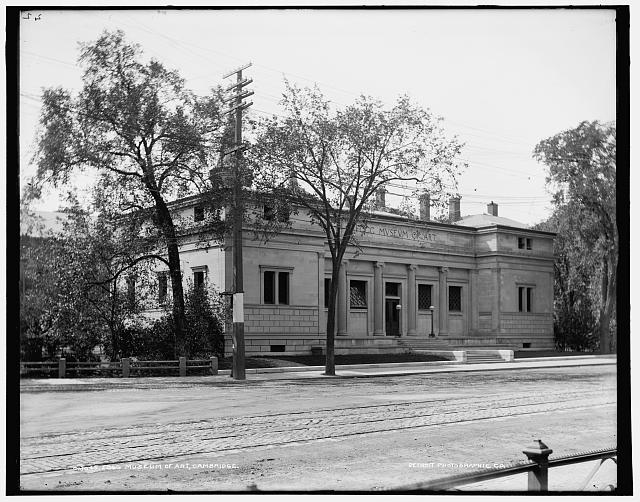

Decrying Richard Morris Hunt’s design for the Fogg Museum, Emerson claimed “it is a pity that there is not less museum and more fog, in order that it might be made invisible forever, in which case, it might be allowed to remain.”

“When you talk with Mr. Emerson you will be pretty sure to have your ideas stirred up,” claimed The Boston Morning Journal in 1903. With an ability to connect familiar topics with broader themes, the paper celebrated the architect’s skills as a public speaker. Emerson’s claimed that “Boston was built in England” the newspaper noted, but explained for its readers the historical grounding and facts behind such a bold statement. Just as Emerson’s designs were reprinted in periodicals, spreading across America and abroad, so too were discussions of his lectures. The South Haven Tribune, published in South Haven, Michigan, reprinted much of lecture on Boston’s buildings, demonstrating not only the interest in his claims, but also the far-reach of W. Ralph Emerson’s reputation as a lecturer.