Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

Head to Toe

Hat and Shoe Fashions from Historic New England Clothing is a language. The garments one chooses are a personal vision and a public message. Hats and shoes are fashionable punctuation, finishing an outfit with individual flair. Whether updating last year’s dress or purchased for a special occasion, accessories are directly connected to important moments and memories. They are part of our life story.

Clothing is a language. The garments one chooses are a personal vision and a public message. Hats and shoes are fashionable punctuation, finishing an outfit with individual flair. Whether updating last year’s dress or purchased for a special occasion, accessories are directly connected to important moments and memories. They are part of our life story.

Fashion

Dress—meaning the variety of body coverings humans wear every day—is both public and personal. Defining dress relies on two key concepts: fashion and style. Fashion is a cultural force. Style is a personal choice. To fashion is to make. To style is to manipulate and present. This exhibition invites viewers to experience hats and shoes from multiple perspectives.

Local Produce

New England was a center of American industrialization in the nineteenth century, known especially for its world-famous textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts. In addition, millions of shoes, boots, slippers, bonnets, caps, and straw hats left the factories in Haverhill, Amesbury, and Lynn, Massachusetts, as well as dozens of other towns throughout the region. Small-scale production by homeworkers and boutique designers also contributed piecework and finished garments to consumers. New England entrepreneurial spirit imbued the hat and shoe industries.

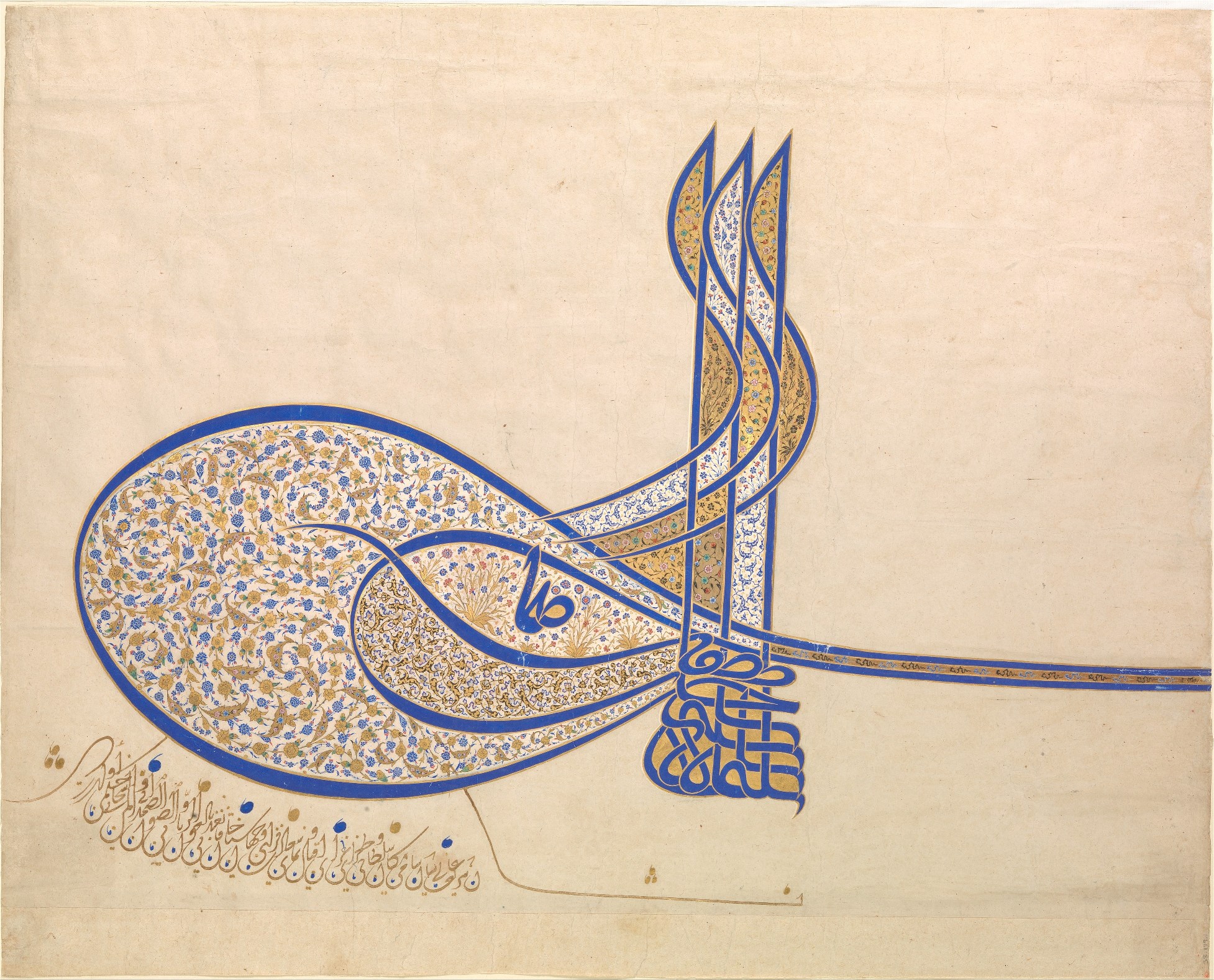

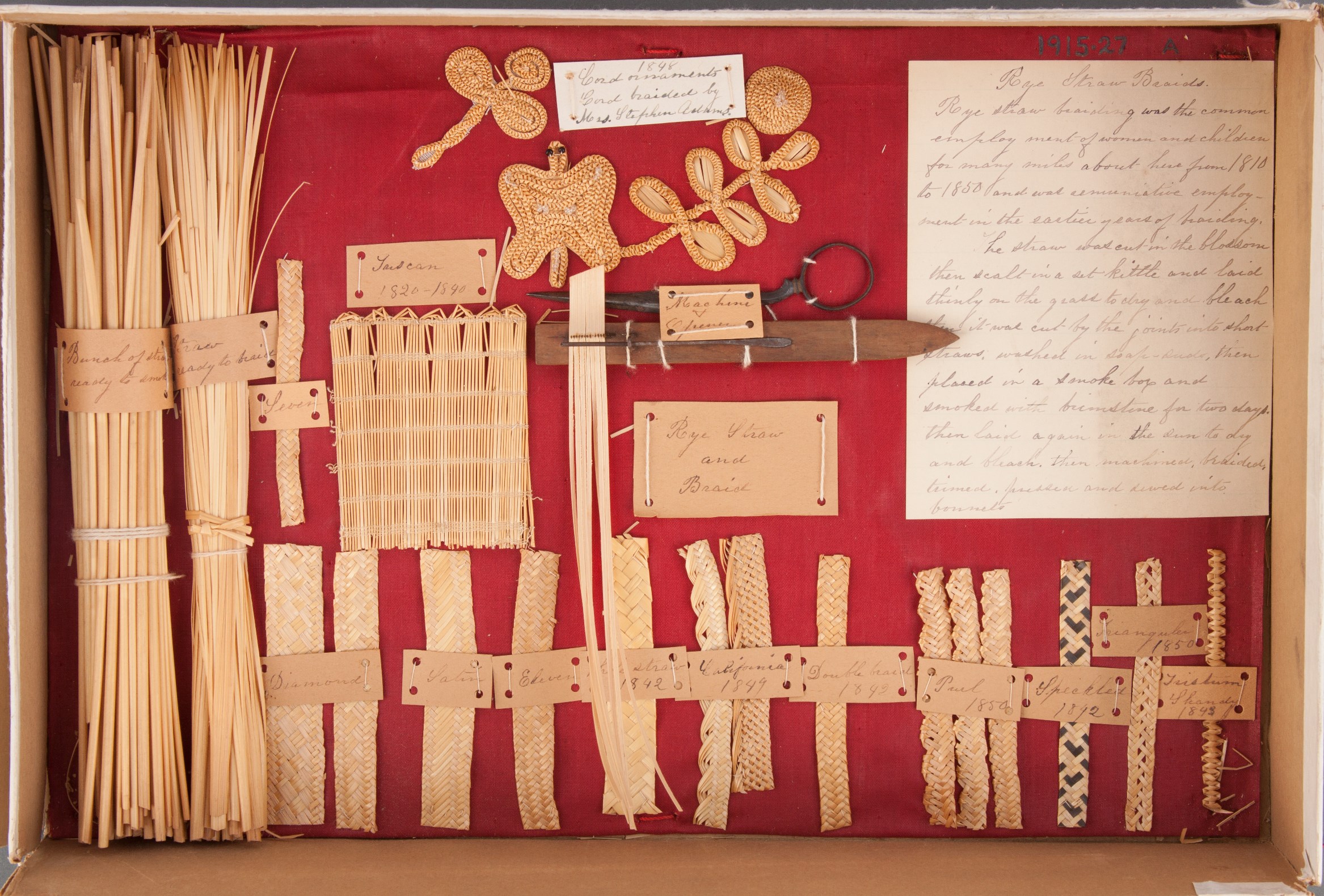

Women at Work: Straw Braiding

Julia A. Adams, who assembled this group of straw braiding samples, worked in a Medway, Massachusetts bonnet factory, most likely the Metcalf factory. Begun in 1842, the Metcalf factory was one of the largest employers in town and part of a regional economy that employed more women in the early to mid-nineteenth century in Massachusetts than textile or shoe production. Many authors over the years have attributed the origins of New England straw bonnet manufacturing to a single woman, Bestey Metcalf, sometimes misidentified as Hannah. The story revolves around an imported Italian “Leghorn” hat Betsey saw in a window but could not afford. Made with fine straw bleached almost white, these beautiful accessories were far beyond Betsey’s modest pocketbook, so the enterprising young woman decided to make her own bonnet with local rye straw. Numerous interviews, letters, and details about Betsey seem to confirm aspects of this story. Miss Metcalf appears to have taught herself to braid, and encouraged her friends as well. But whether rye straw hats developed from the nimble fingers of a single inventor is less important than the impact domestic bonnet production had on the regional economy.

Beginning in the 1820s and 1830s over forty-eight percent of women who worked were employed in the production of straw and palm-leaf hats. Straw braiding paid half as much as textile or shoe factory labor, but it remained a consistent source of income and independence for many women in New England throughout the nineteenth century. Workers picked up raw materials from their local dry good merchant and braided lengths of split rye straw at home. They were typically paid by the foot of completed braid returned to the merchant, who then sold it to specialist milliners for making up into hats. Quite often straw braiders worked for the same stores where they shopped for their families. Later in the 1850s the first “factories” concentrated that portion of straw hat production under one roof, but they still relied on rural outwork in the region for braid production. Only the largest factories were vertically integrated and could take rye straw from raw product to finished hat.

Special Shoes

These shoes are most likely Martha Stevens’s wedding shoes. Unfortunately little information remains about Martha specifically other than her generous donations to charity and family upon her death, but she married John Stevens and resided in Ashford, Connecticut. The shoes were special enough to bequeath to her relative and the executor of her will, Increase Sumner. His son, General William H. Sumner, in turn gave the shoes to the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1872. The shoes received special mention in the Stoddard family history, where author Elijah Stoddard noted “a family relic of Mrs. Stevens, a pair of old-fashioned high-heeled shoes, of rich material” in the Sumner family.

Winthrop Gray, from a family of Lynn, Massachusetts cordwainers, moved to Boston to set up his shoemaking business. He placed his shop near a local tavern, the Cornfield, which in 1763 was on Union Street. Only in business for a few years, Gray went on to serve as a Captain in the Continental Army from 1776 to 1779 then in 1781 as inn holder of the American Exchange Tavern on State Street in Boston. At only age 43, Gray died the following year.

Innovation

Significant innovations in the nineteenth century, such as flexible, watertight footwear, patented arch supports, and substitutes for expensive imported straw bonnets, changed New England’s fashion landscape. Innovators built on existing expertise and technology, creating new materials, designs, and concepts.

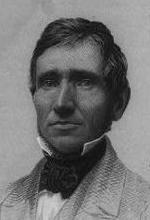

Goodyear and Rubber Boots

The man responsible for everything from rubber boots to bicycle tires began by mixing chemicals in his family’s porcelain teacups. Convinced that he could find a way to keep rubber from melting in summer and cracking in winter, Charles Goodyear spent years trying to perfect the formula before he stumbled on adding sulfur to heated rubber. By 1844, patent in hand, Goodyear licensed the formula to several companies in the burgeoning rubber town of Naugatuck, Connecticut. Unfortunately, Goodyear spent his money as soon as he earned it, fighting numerous patent infringements in court. Goodyear’s legacy is most visible in the company named in his honor, based in Akron, Ohio and in the millions of sneakers, tires, and other rubber-based products still on the market today.

This pair in the exhibition were made by the Wales Goodyear Shoe Company, manufacturer (in business 1845-1916) in Naugatuck, Connecticut, around 1880-1900. The donor’s mother knit the tops to wear on winter carriage rides in the late 19th century.

Style

Stylish women and men have a sense about how to tell their personal stories with clothing. Designer Bill Blass called it, “a matter of instinct.” Style applies equally to the designer, whose creations embody her or his vision against a backdrop of social trends, current events, and the larger historical narrative. Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, founder of one of the world’s most iconic fashion brands, once said, “Fashion fades, only style remains the same.” If clothing is a language, then style is an individual’s poem or essay, sentence or exclamation point.

Going Out

Dressing up to go out—whether calling for tea or dancing at a disco—required accessories with particular flair.