Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

Land & Sea

Gallery One

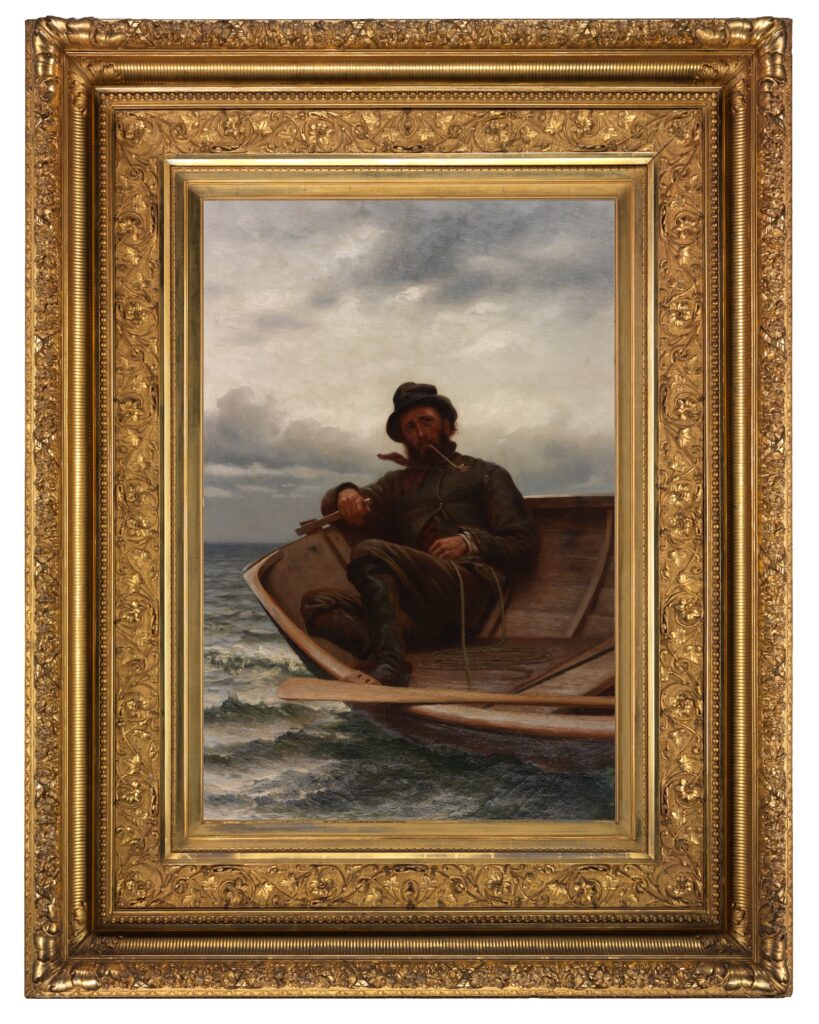

Artists have celebrated New England’s scenery for more than 200 years. In lush summer or frigid winter, they have depicted iconic scenes of majestic wilderness and well-organized farms, ordinary meadows and marshes, and towns large and small. Equally alluring has been New Englanders’ close relationship with the sea. With so much wealth derived from shipping and fishing, artists’ interest was inevitable.

Looming in the backstories of many paintings are the harsh realities of industrialization and urban expansion, which painters generally avoided depicting. And yet while evading those issues, in some ways these paintings underscore them. Celebrating and preserving New England’s natural beauty is of urgent concern today, a fact that makes these glimpses of the region in the past particularly meaningful.

For a closer look at the paintings in this gallery, click on the images below and use the zoom feature. Some of the paintings have even more information, including historical photographs, additional context, and a glimpse into the work of the conservation lab. (If the images or text seem too small or large in your browser, try clicking ctrl and + or – key to adjust.)

Gallery 1: Land and Sea Gallery 2: At Home Gallery 3: New England’s People Gallery 4: The Wide World

Winter Scene

William H. Titcomb (1824–1888)

New Hampshire, 1851

Oil on canvas

28 ½ x 36 3/8 in.

Gift of Ralph May

1971.590

With its smoking chimney on a snow-covered house and its sunset-tinged sky, William Titcomb’s depiction of a wintery New Hampshire landscape is iconic. Children play on a pond as a farmer leads home his ox pulling a sledge filled with the lumber he has cut down for next year’s use. As appealing as the scene is, the approaching cloud cover in the distance and the fallen tree in the foreground are troubling.

Ezekial Hersey Derby Farm

Michele Felice Cornè (1752–1845)

Salem, Massachusetts, c. 1800

Oil on canvas

45 1/8 x 57 3/4 in.

Gift of Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little

1992.170

As a trustee of the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture, founded in 1792, Ezekiel Hersey Derby (1772–1852) was keenly interested in introducing scientific principles to farming practices. Some of those principles are seen here—deep plowing, working in an orderly and neat manner, and using manure as fertilizer. The stone walls surrounding the fields suggest that Derby faced the same challenges that confronted most New England farmers. Boulders and rocks appear in this region like an ineradicable annual crop, the shallow soil and freeze-thaw cycle bringing them to the surface year after year.

View of Boston

Attributed to Victor De Grailly (1808–1889) after William H. Bartlett (1809–1854)

Paris, c. 1845

Oil on canvas

30 x 37 3/4 in.

Gift of Eleanor Norris in memory of her mother, Madeleine Tinkham Miller

2004.12

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Boston was a thriving port and a densely populated city. This view is taken from Dorchester Heights in South Boston looking northeast toward Boston, with Charlestown beyond. The painting is thought to have been done by French artist Victor De Grailly, who, although best known for his views of America, never set foot in the country. He found a profitable market copying published prints of American cities and landscapes by British artist William H. Bartlett.

Conservation funds provided by Robert Bayard Severy in memory of his father, Robert Pease Severy (1899-1992)

A Country Landscape

Charles Harold Davis (1856–1933)

Mystic, Connecticut, 1900–15

Oil on canvas

42 ½ x 50 ¼ in.

Gift of the Stephen Phillips Memorial Charitable Trust for Historic Preservation

2006.44.770

A Massachusetts native, Charles Davis decided to pursue art after visiting a Boston exhibition of landscapes in the French Barbizon manner, a style evident in the Bannister and Longfellow paintings in this gallery. After training in France, he settled in Mystic, Connecticut, where he became well known for his “cloudscapes.” Many of his paintings, like this one, utilized a low horizon that calls viewers’ attention to this region’s ever-changing cloud formations.

View of Boston Across the Flats

Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow (1845–1921)

Boston, 1876

Oil on canvas

14 3/8 x 18 1/8 in.

Gift of Dorothy S. F. M. Codman

1969.821

This view from Winthrop is one that Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow’s contemporaries would have recognized by the skyline’s distinctive features, including the steeple of the Park Street Church and the dome of the Massachusetts State House. The trees in the foreground draw viewers into the composition, which relies on the huge sky to underscore the vast flatness below.

Admired for figure paintings as well as landscapes, the artist was the son of the famous poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, attended Harvard University, then studied art in France, and traveled widely.

View of Boston across the Flats

Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow

Where Is This?

Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow made this scene of Boston while looking west from Winthrop, probably from Point Shirley. In the twentieth century, landfill was added to the flats to create the area that has become Boston Logan International Airport. This detail of a U.S. Coast Survey chart offers a view of Boston Harbor in 1863, almost fifteen years before Longfellow painted this scene. Colored in brown, the flats are seen to the right of Boston’s historic center.

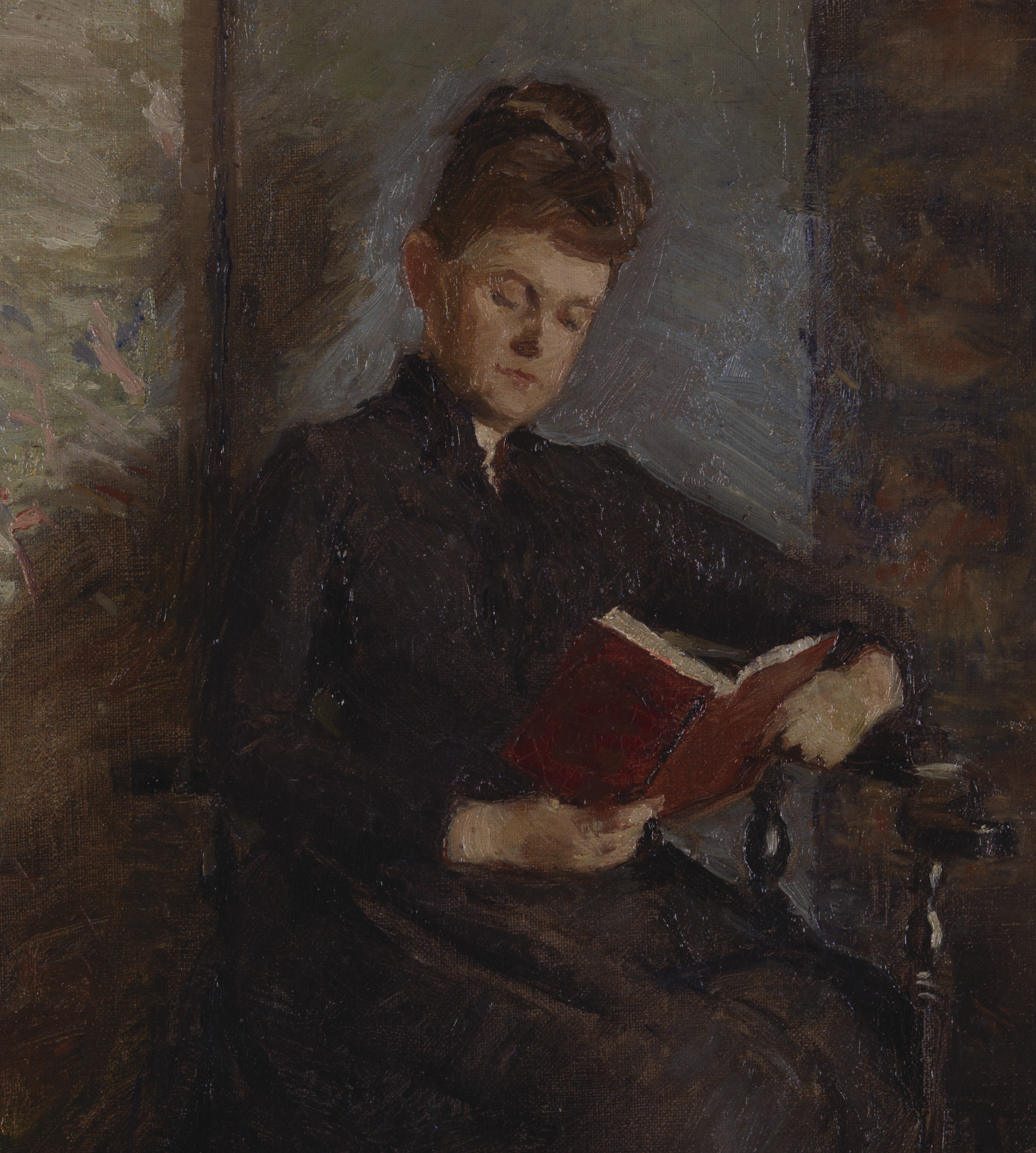

Woman Reading Under a Tree

Edward Mitchell Bannister (c. 1828–1901)

Probably Rhode Island, 1880–85

Oil on canvas

14 3/8 x 18 3/8 in.

Museum purchase

2018.35.1

Born in Canada, Edward Mitchell Bannister was one of the few black artists to be widely recognized in the United States before 1900. Arriving to accept a prize at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, he was refused entry, but finally received the medal after fellow exhibitors protested. Bannister taught at the Rhode Island School of Design and painted local scenery using techniques of the French Barbizon School, which prioritized nature’s ordinary beauties over iconic views such as Benjamin Champney’s Mount Chocorua. Here, a woman reads while breezes flutter the leaves and grasses.

Woman Reading Under a Tree

Edward Mitchell Bannister

While living in Boston in the early 1850s, Edward Mitchell Bannister could not have ignored the city’s growing fascination with the Barbizon “School” (style) of painting then being imported from France. In contrast to the meticulous detail and strong coloring employed by such then-fashionable Hudson River Valley and White Mountains landscapists as Thomas Cole and Benjamin Champney, Barbizon artists emphasized cooler and more tonally unified coloring, looser brushwork, and softer forms.

The first Barbizon painting exhibited in Boston (1853) was created by the now-forgotten Frenchman Eugène Cicéri, and the following year Bostonians began admiring the French master Jean-François Millet, whose scenes of peasants in the fields were especially popular. The vogue for Barbizon pictures gained momentum in 1855, when the talented and well-connected artist William Morris Hunt returned to Boston after twelve years in Europe, including a period of study with Millet. Hunt helped an 1858 exhibition of Barbizon paintings at the Boston Athenaeum become a huge success, inspiring both New England collectors and artists as wide-ranging in age and background as Bannister, Longfellow, and Davis—all represented in this gallery. Some New Englanders also perceived in Barbizon paintings a moral element that appealed to them; the collector Thomas Gold Appleton wrote of Millet’s paintings: “They have a Biblical severity and remind us of the gravest of the Italian masters.”

Note Cicéri’s placement of two patches of daylight near the center of his composition—one in the tree canopy and the other on the forest floor—to remind viewers that the weather beyond this darkened woodland was bright. Likewise, in his painting Bannister deftly contrasted light and shadow, even using a patch of blue sky visible through the foliage at top left.

Like Hunt, Bannister included a female figure to provide a sense of scale and to suggest the harmony of nature and humankind. Notice Hunt’s deft orchestration of the vertical tree trunks to create a rhythm across the picture plane—something Bannister also handled masterfully.

Women Reading

In Bannister’s painting, a woman reads while gentle breezes flutter the leaves and grasses around her. This scene evokes the Massachusetts poet-philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Transcendentalist belief in the unity of nature and people. In Nature (1849), he wrote: “In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, — no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair… I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.” Emerson’s readers, possibly including Bannister, no longer saw nature as something to be conquered, but rather something that offered peace, which this woman may well have been experiencing.

Although depicted throughout the history of art, women reading took on an urgent symbolic power in the later nineteenth century as more women demanded, and secured, a higher education. Bannister often took his art students—both men and women—outside Providence to paint and sketch outdoors. The woman seen here may in fact have been one of his students, though the flock of geese grazing at left would have inferred to some viewers that she was instead a farm girl tending them. Compare the tiny detail of the woman reading here with artist Mabel Stuart’s Portrait of Mary Elizabeth Cutting Buckingham in this exhibition’s second gallery. By situating Buckingham indoors and centering the composition on her, the artist made reading the subject of her composition, rather than an incidental occurrence tucked off to one side.

Paintings from the Eustis Estate

ComparisonsBannister’s capacity to find luminosity and poetry in seemingly ordinary scenery was sustained by the younger artist Laura Coombs Hills (1859–1952). Hanging in the parlor on the ground floor of the Eustis Estate is The Shaded Stream, which she painted in her hometown of Newburyport, Massachusetts. Although Hills became better known for her pastels and miniatures, she excelled at Barbizon-inspired landscapes like this, made around the same time Bannister created his.

Right: Laura Coombs Hills (1859–1952), The Shaded Stream, c. 1880, oil on canvas, 24 x 28 x 3 ¼ in., Museum Purchase, 2016.56.1.

Learn more about The Shaded Stream below.

Learning to Look

Most of us first look at a painting and see the overall image. We imagine being in the place where the artist was. Has the artist captured the mood of a rainy day in the city? What was the person in this portrait like? But we can also learn something by looking more closely at what’s on the canvas. How has the way the artist applied the paint enhanced the image? How does the composition direct your eye around the scene? How do the choices this artist made relate to those made by another artist?

Several areas of Edward Mitchell Bannister’s Woman Reading Under a Tree merit closer looking. Click the hot spots in the image for more details.

The arching branch at center right guides our eye toward the massive central tree trunk in the distance and complements the verticality of the adjacent trunks.

The patch of blue sky visible through the foliage at top left offers us a sense of perspective and a reminder of how clear the weather is.

Bannister masterfully contrasted brilliant sunlight on the grass with shadows in the foreground.

to learn more

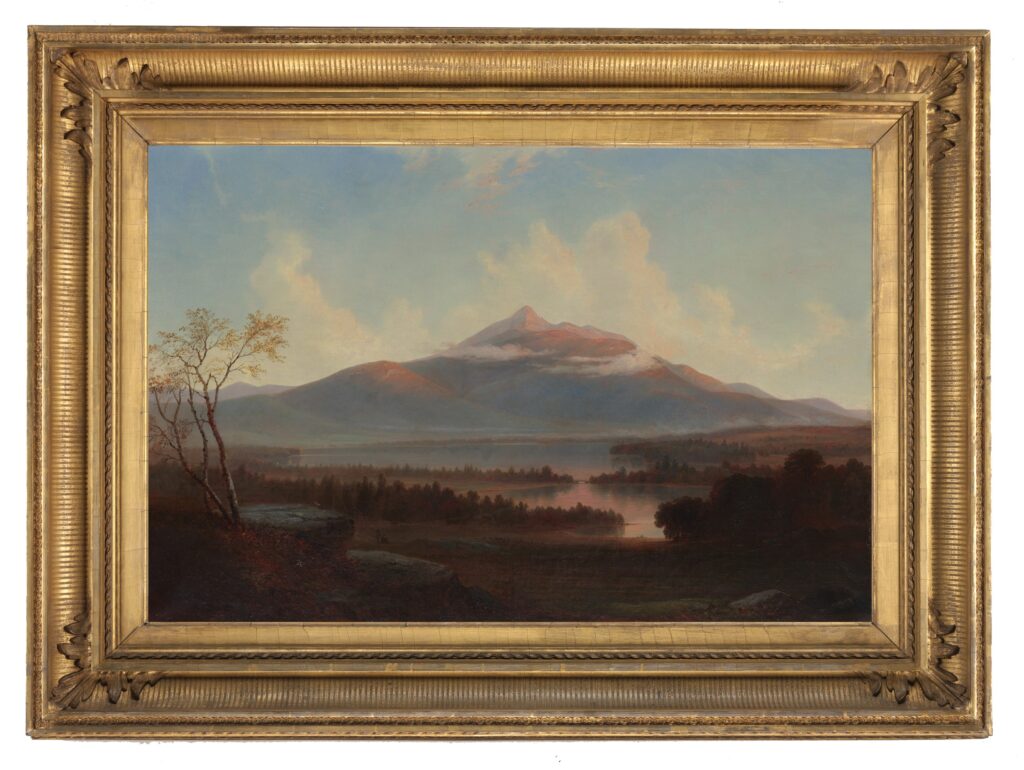

Mount Chocorua

Benjamin Champney (1817–1907)

Boston or New Hampshire, 1860

Oil on canvas

28 3/16 x 38 7/8 in.

Gift of the estate of Jane N. Grew

1920.461

Mount Chocorua is in the southern reaches of the White Mountains in New Hampshire. Part of the Appalachian range, these mountains were among New England’s most popular tourist attractions in the nineteenth century. Artists flocked to the area, drawn not only to the region’s beauty, but also to the camaraderie established by this painter, Benjamin Champney, whose summer residence and studio in North Conway attracted many like-minded men and women.

From the Conservator's Notebook

A Tale of Two FramesHistoric New England objects conservator Michaela Neiro supervised the conservation treatment and stabilization of this exhibition’s paintings and frames over a period of two years. The Conservator’s Notebook features explanations and insights that Michaela has drawn from her project notebook, including close-up photographs showing how the work was done.

Right: Frank Henry Shapleigh (1842–1906), A Country Home, 1866, oil on canvas, 27 9/16 x 39 ½ in., Bequest of Amelia Peabody, 1985.662. Located in Gallery Two.

Take a look at the two paintings above. Both were made and framed around 1860, when this style of frame was very typical. All the decorative molding elements—the outermost bead, the serpentine braid, the incised cove, and the corner ornament—were cast out of a putty-like material containing linseed oil and whiting called composition or “compo.” The ability to cast decorative elements instead of carving them allowed for much more elaborate moldings, and several at a time, to be used on frames and thus keep costs down. Because the compo was smooth coming out of the mold, gesso and bole were unnecessary. A thin coat of oil size was brushed on and the compo could be gilded very quickly. The oil gilded areas could not be burnished, however, and therefore they appear matte. The thin strips between the different compo decorations, called flats, were made of wood coated with gesso and bole. These flats were burnished to produce a shiny contrast to the oil gilding and make for a more interesting frame.

Benjamin Champney’s Mount Chocorua has hung at Barrett House (see Forest Hall in Gallery Two) for years and now shows its age. The compo on its frame has shrunk and cracked, and the gold has worn through from years of dusting. The oil size has dried and shrunk, causing faults in the thin gold layer and exposing the tan-colored compo below. Along the bottom edge and the high spots of detail, the exposed compo has darkened with dirt. This aged surface is very typical, natural, and acceptable considering its age.

The frame for A Country Home by Shapleigh looks remarkably good for its age – and so does the painting. Over 150 years old and no wrinkles! How can this be? The framed painting came to Historic New England in 1985. Sometime before then both painting and frame were given a facelift. The painted canvas was removed from its original stretcher and adhered to a Masonite board. This is a somewhat heavy-handed treatment, but the conservator likely had few other options to preserve what must have been a very delicate painting. The frame was likely in equally rough condition. Conserving a badly damaged frame so that it maintains its appearance of age is a very time-consuming, and thus expensive, process. It’s far easier to restore the frame to its original appearance by putting new gilding over old and that’s what happened when this was restored before it came to Historic New England. It looks fresh and new and much more “golden” than the frame on the Champney. This aesthetic was likely quite appropriate for the modern home it came from, but at Historic New England, we prefer items to have age-appropriate patina.

In the video below, Michaela Neiro describes the issues on the Champney frame that the conservation team worked to address.

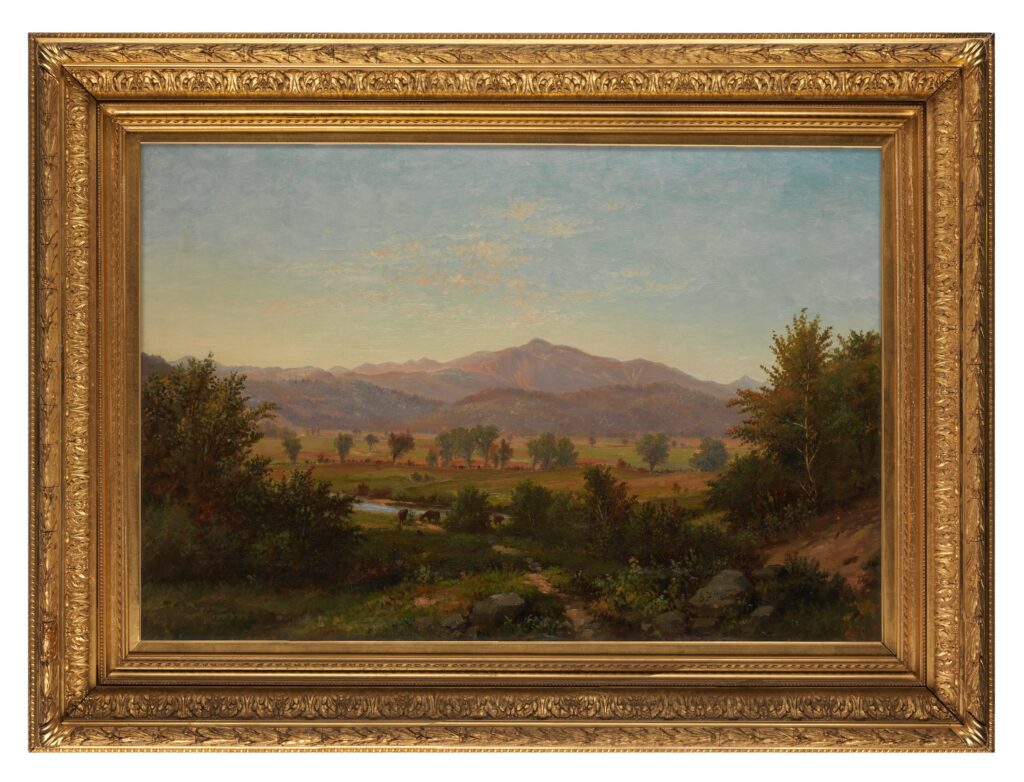

View of Mount Washington

George Frank Higgins (c. 1835–after 1900)

New Hampshire, 1868

Oil on canvas

33 7/8 x 45 7/8 in.

Gift of Caroline Barr Wade

1948.248

Little is known about the artist who painted this view. The painting is here so we can explore different artists’ approaches to similar subjects. Scroll back and forth between this painting and the one above or click here to view it side by side with the Champney painting of Mount Chocorua under Comparison section. Do you notice, for instance, that Champney’s is more atmospheric? Now look at the handling of the depth of field. Champney’s painting moves seamlessly from foreground, to middle ground, to distance, to sky, whereas here each reads like a separate band. The differences might be explained by Champney’s greater skill, but they’re also the result of choices each artist made.

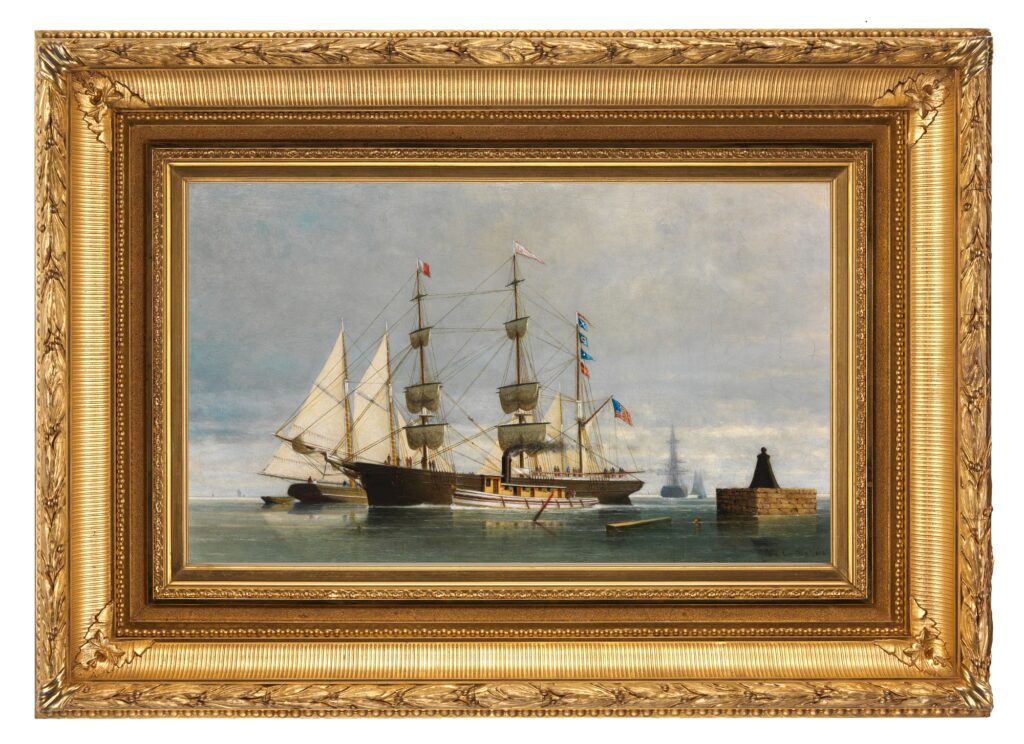

Sunny Morning, Gloucester Harbor

George Wainwright Harvey (1855–1930)

Gloucester, Massachusetts, late 1880s

Oil on canvas

17 5/8 X 23 5/16 in.

Gift of the Stephen Phillips Memorial Charitable Trust for Historic Preservation

2006.44.670

Artists have long admired the charm of New England’s ports, often ignoring that they are also sites of labor and commerce. The son of a Gloucester sea captain, Harvey deftly composed this scene using the strong vertical thrust of the boat’s sails, which is sustained in its reflection. He married photographer Martha Hale Rogers and they spent many years in Europe before returning to the Cape Ann region. Her photograph shown below reveals their artistic affinity.

Sunny Morning, Gloucester Harbor

George Wainwright Harvey

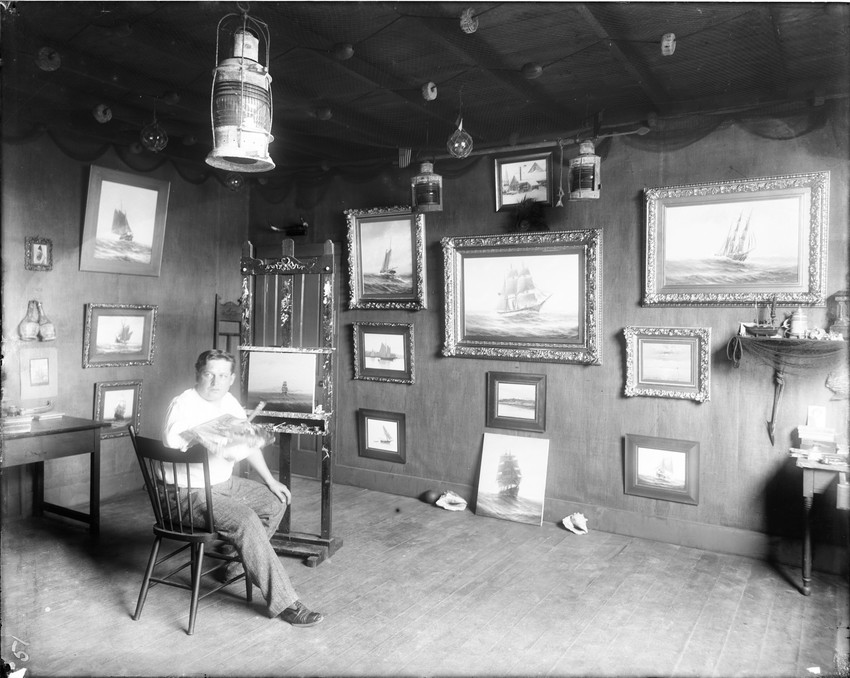

Martha Hale Rogers Harvey’s Photographs

The black-and-white photographs made by Martha Hale Rogers Harvey share the spirit of the paintings created by her husband George Harvey. Capturing picturesque aspects of life along the water in Gloucester, the Harveys were at the heart of its Rocky Neck artists’ colony, which still exists on a peninsula in the town’s working harbor. Among the talents who worked there at various times in the nineteenth century were Winslow Homer, Frank Duveneck, and Childe Hassam, yet most of the artists active there are not household names today. The six photographs illustrated here reflect not only Martha Harvey’s gift for atmosphere and composition, but also the diversity of her vision: Some scenes are as formally elegant as her husband George’s painting of a schooner, while others reveal the strenuous labor and primitive conditions endured by Gloucester’s fishermen. Particularly charming are the scene of George Harvey sitting with a cat and the snapshot catching men relaxing on a pier.