Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

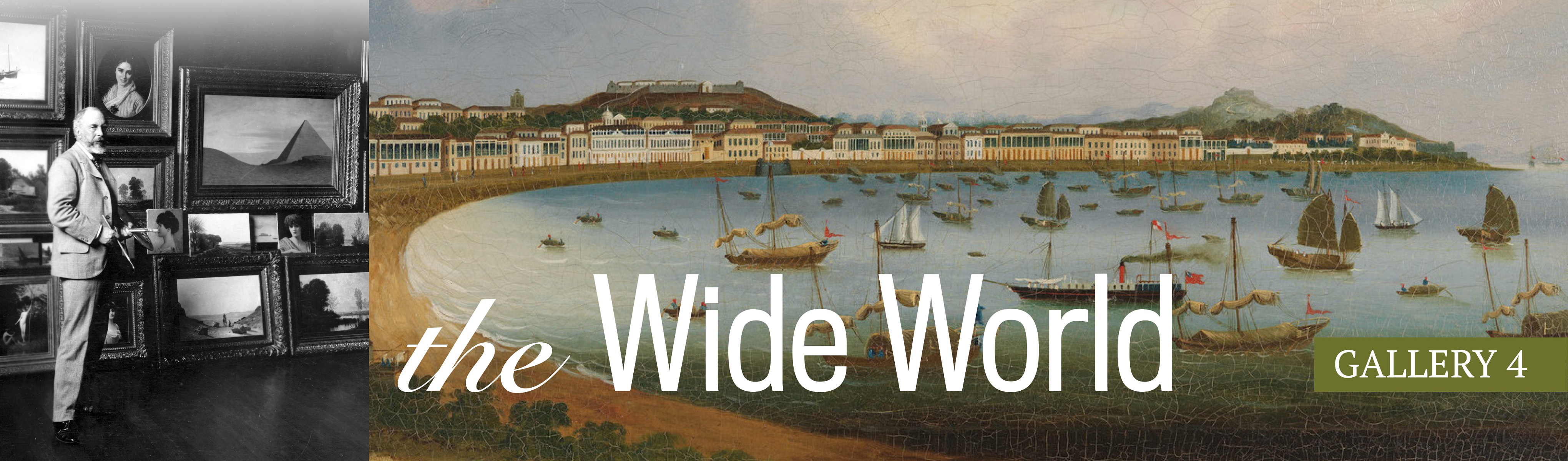

Land & Sea

Gallery One

Artists have celebrated New England’s scenery for more than 200 years. In lush summer or frigid winter, they have depicted iconic scenes of majestic wilderness and well-organized farms, ordinary meadows and marshes, and towns large and small. Equally alluring has been New Englanders’ close relationship with the sea. With so much wealth derived from shipping and fishing, artists’ interest was inevitable.

Looming in the backstories of many paintings are the harsh realities of industrialization and urban expansion, which painters generally avoided depicting. And yet while evading those issues, in some ways these paintings underscore them. Celebrating and preserving New England’s natural beauty is of urgent concern today, a fact that makes these glimpses of the region in the past particularly meaningful.

For a closer look at the paintings in this gallery, click on the images below and use the zoom feature. Some of the paintings have even more information, including historical photographs, additional context, and a glimpse into the work of the conservation lab. (If the images or text seem too small or large in your browser, try clicking ctrl and + or – key to adjust.)

Gallery 1: Land and Sea Gallery 2: At Home Gallery 3: New England’s People Gallery 4: The Wide World

View of Boston

Attributed to Victor De Grailly (1808–1889) after William H. Bartlett (1809–1854)

Paris, c. 1845

Oil on canvas

30 x 37 3/4 in.

Gift of Eleanor Norris in memory of her mother, Madeleine Tinkham Miller

2004.12

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Boston was a thriving port and a densely populated city. This view is taken from Dorchester Heights in South Boston looking northeast toward Boston, with Charlestown beyond. The painting is thought to have been done by French artist Victor De Grailly, who, although best known for his views of America, never set foot in the country. He found a profitable market copying published prints of American cities and landscapes by British artist William H. Bartlett.

Conservation funds provided by Robert Bayard Severy in memory of his father, Robert Pease Severy (1899-1992)

A Country Landscape

Charles Harold Davis (1856–1933)

Mystic, Connecticut, 1900–15

Oil on canvas

42 ½ x 50 ¼ in.

Gift of the Stephen Phillips Memorial Charitable Trust for Historic Preservation

2006.44.770

A Massachusetts native, Charles Davis decided to pursue art after visiting a Boston exhibition of landscapes in the French Barbizon manner, a style evident in the Bannister and Longfellow paintings in this gallery. After training in France, he settled in Mystic, Connecticut, where he became well known for his “cloudscapes.” Many of his paintings, like this one, utilized a low horizon that calls viewers’ attention to this region’s ever-changing cloud formations.

View of Boston Across the Flats

Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow (1845–1921)

Boston, 1876

Oil on canvas

14 3/8 x 18 1/8 in.

Gift of Dorothy S. F. M. Codman

1969.821

This view from Winthrop is one that Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow’s contemporaries would have recognized by the skyline’s distinctive features, including the steeple of the Park Street Church and the dome of the Massachusetts State House. The trees in the foreground draw viewers into the composition, which relies on the huge sky to underscore the vast flatness below.

Admired for figure paintings as well as landscapes, the artist was the son of the famous poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, attended Harvard University, then studied art in France, and traveled widely.

Woman Reading Under a Tree

Edward Mitchell Bannister (c. 1828–1901)

Probably Rhode Island, 1880–85

Oil on canvas

14 3/8 x 18 3/8 in.

Museum purchase

2018.35.1

Born in Canada, Edward Mitchell Bannister was one of the few black artists to be widely recognized in the United States before 1900. Arriving to accept a prize at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, he was refused entry, but finally received the medal after fellow exhibitors protested. Bannister taught at the Rhode Island School of Design and painted local scenery using techniques of the French Barbizon School, which prioritized nature’s ordinary beauties over iconic views such as Benjamin Champney’s Mount Chocorua. Here, a woman reads while breezes flutter the leaves and grasses.

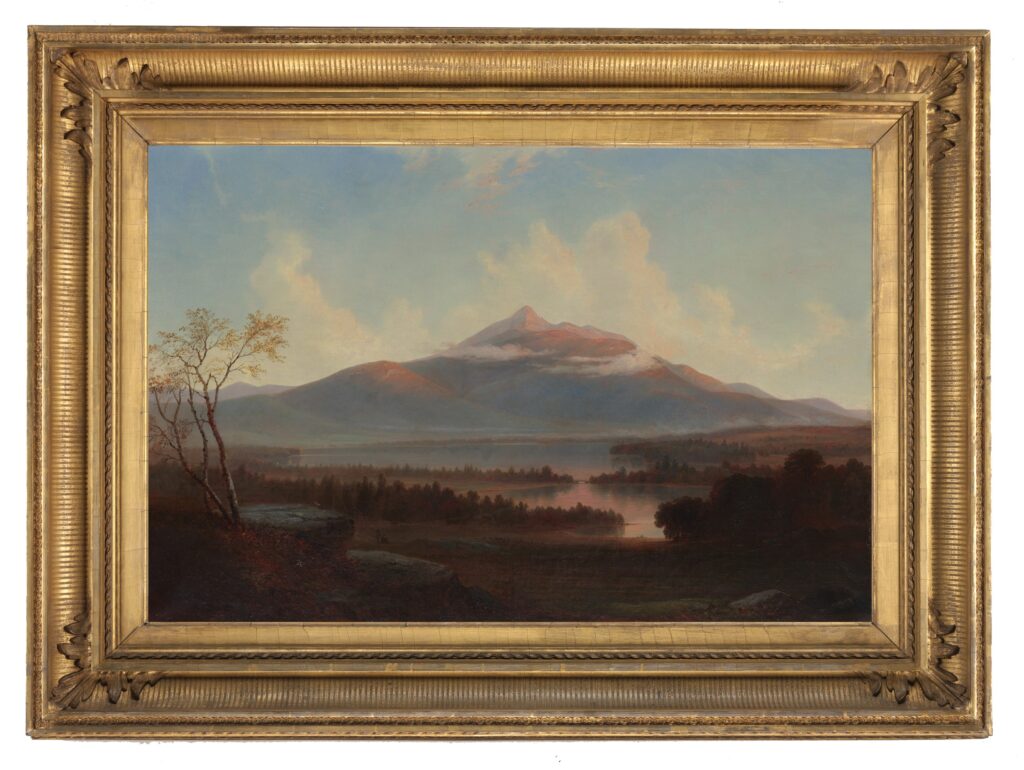

Mount Chocorua

Benjamin Champney (1817–1907)

Boston or New Hampshire, 1860

Oil on canvas

28 3/16 x 38 7/8 in.

Gift of the estate of Jane N. Grew

1920.461

Mount Chocorua is in the southern reaches of the White Mountains in New Hampshire. Part of the Appalachian range, these mountains were among New England’s most popular tourist attractions in the nineteenth century. Artists flocked to the area, drawn not only to the region’s beauty, but also to the camaraderie established by this painter, Benjamin Champney, whose summer residence and studio in North Conway attracted many like-minded men and women.

Sunny Morning, Gloucester Harbor

George Wainwright Harvey (1855–1930)

Gloucester, Massachusetts, late 1880s

Oil on canvas

17 5/8 X 23 5/16 in.

Gift of the Stephen Phillips Memorial Charitable Trust for Historic Preservation

2006.44.670

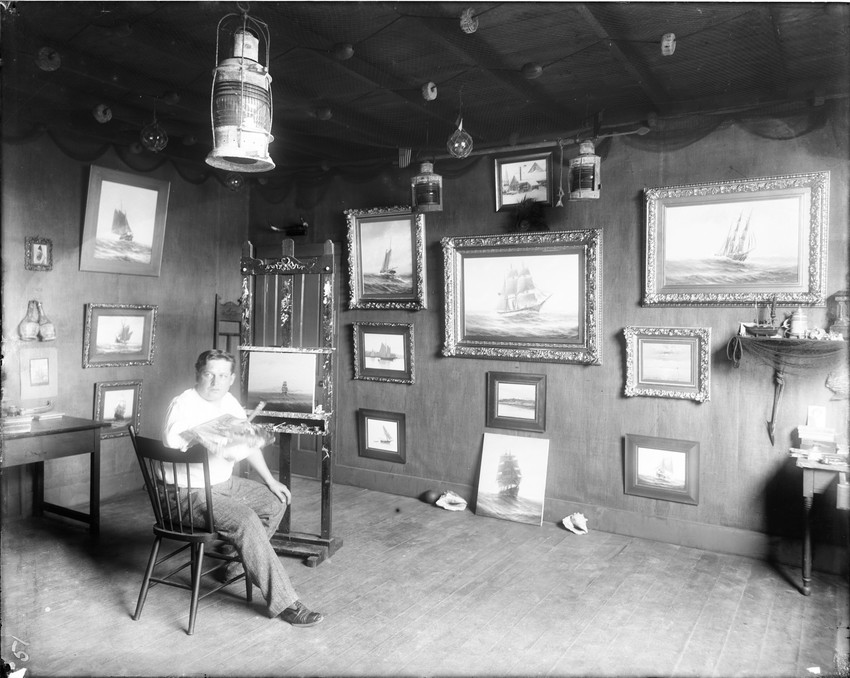

Artists have long admired the charm of New England’s ports, often ignoring that they are also sites of labor and commerce. The son of a Gloucester sea captain, Harvey deftly composed this scene using the strong vertical thrust of the boat’s sails, which is sustained in its reflection. He married photographer Martha Hale Rogers and they spent many years in Europe before returning to the Cape Ann region. Her photograph shown below reveals their artistic affinity.

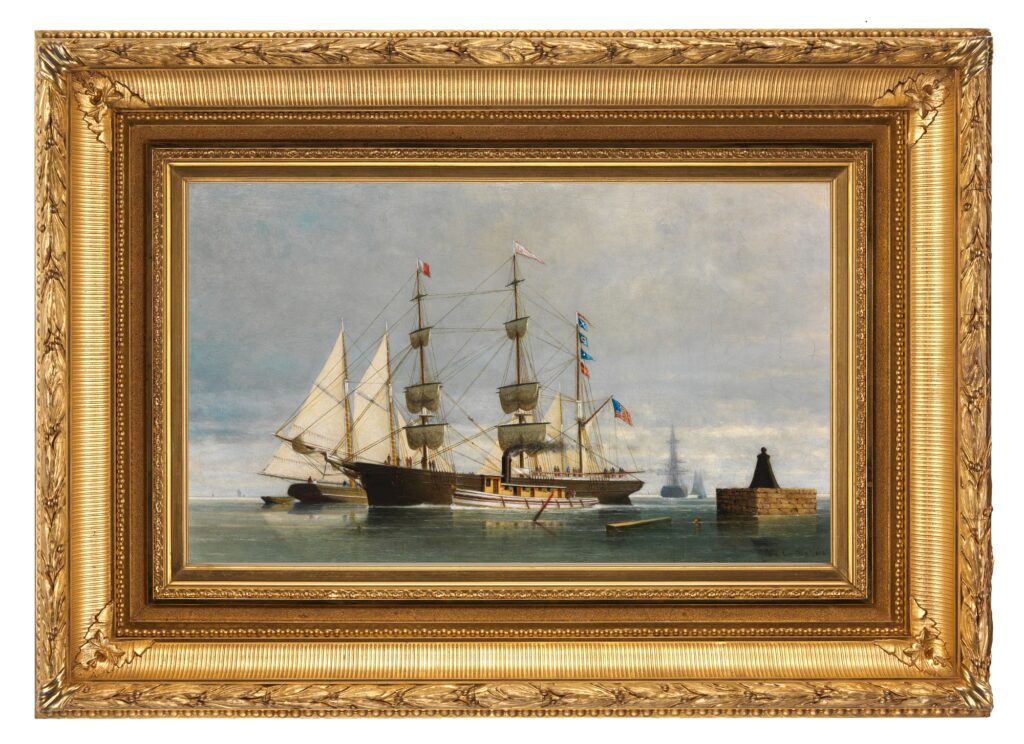

Off Nix’s Mate, Boston Harbor

George Curtis (1826–1881)

Boston, c. 1876

Oil on canvas

20 ½ x 28 3/8 in.

Gift of the Stephen Phillips Memorial Charitable Trust for Historic Preservation

2006.44.599

New England’s economic success depended on commercial vessels such as this one, so throughout the nineteenth century proud shipowners commissioned vast numbers of such “portraits.” This U.S.-flagged vessel floats in Boston Harbor at Nix’s Mate, a tiny island identifiable by the channel marker at right. One flag indicates that a harbor pilot has come aboard, and a tugboat bobs in the foreground. Curtis added the floating debris to guide our eye deeper into the scene. Crew members are shown standing on a deck that would have actually been much lower.

Winter Scene

William H. Titcomb (1824–1888)

New Hampshire, 1851

Oil on canvas

28 ½ x 36 3/8 in.

Gift of Ralph May

1971.590

With its smoking chimney on a snow-covered house and its sunset-tinged sky, William Titcomb’s depiction of a wintery New Hampshire landscape is iconic. Children play on a pond as a farmer leads home his ox pulling a sledge filled with the lumber he has cut down for next year’s use. As appealing as the scene is, the approaching cloud cover in the distance and the fallen tree in the foreground are troubling.

Ezekial Hersey Derby Farm

Michele Felice Cornè (1752–1845)

Salem, Massachusetts, c. 1800

Oil on canvas

45 1/8 x 57 3/4 in.

Gift of Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little

1992.170

As a trustee of the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture, founded in 1792, Ezekiel Hersey Derby (1772–1852) was keenly interested in introducing scientific principles to farming practices. Some of those principles are seen here—deep plowing, working in an orderly and neat manner, and using manure as fertilizer. The stone walls surrounding the fields suggest that Derby faced the same challenges that confronted most New England farmers. Boulders and rocks appear in this region like an ineradicable annual crop, the shallow soil and freeze-thaw cycle bringing them to the surface year after year.

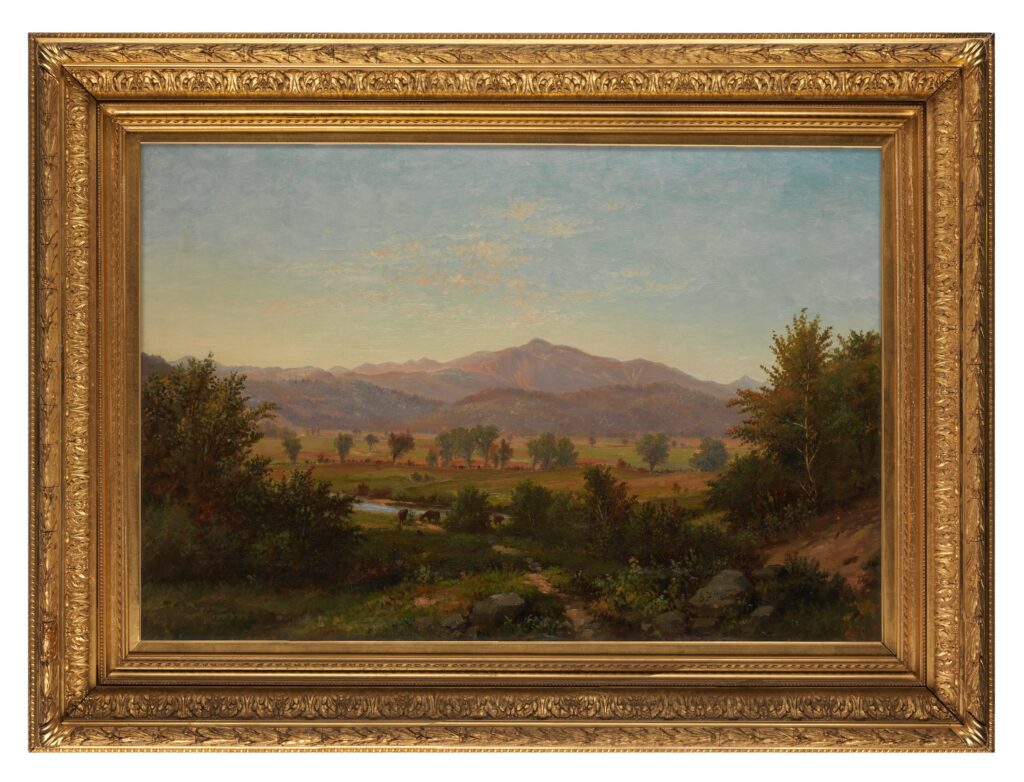

View of Mount Washington

George Frank Higgins (c. 1835–after 1900)

New Hampshire, 1868

Oil on canvas

33 7/8 x 45 7/8 in.

Gift of Caroline Barr Wade

1948.248

Little is known about the artist who painted this view. The painting is here so we can explore different artists’ approaches to similar subjects. Scroll back and forth between this painting and the one above or click here to view it side by side with the Champney painting of Mount Chocorua under Comparison section. Do you notice, for instance, that Champney’s is more atmospheric? Now look at the handling of the depth of field. Champney’s painting moves seamlessly from foreground, to middle ground, to distance, to sky, whereas here each reads like a separate band. The differences might be explained by Champney’s greater skill, but they’re also the result of choices each artist made.

Chandler Farm

James J. Sawyer (1813–1888)

Pomfret, Connecticut, 1858

Oil on canvas

41 ½ x 55 in.

Gift of Mary B. Holt

1990.193

Chandler Farm is typical of the productive farms that dotted the New England landscape in the mid-nineteenth century when 90 percent of the population was still engaged in some form of agricultural work. When this was painted the farm’s owner, John Chandler, was the fourth generation of his family to work the 100-acre plot of land. Well-maintained stone walls and fences separate specific areas, including the piggery and the tidy kitchen garden.

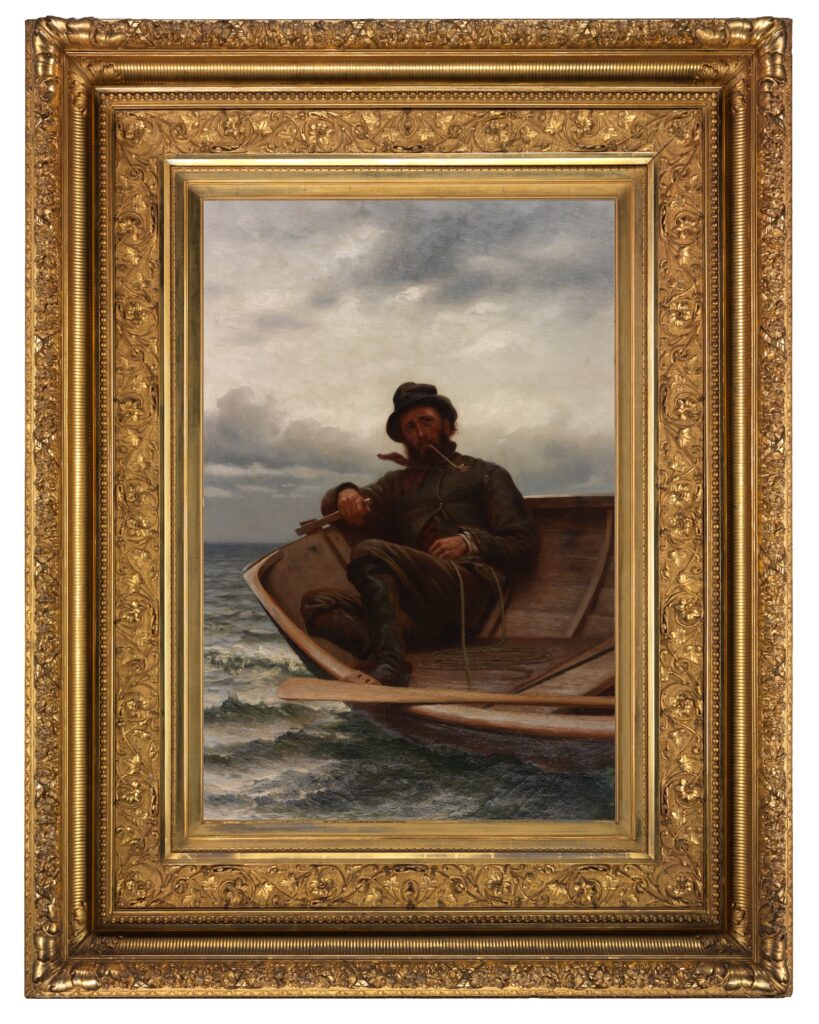

Homeward Bound

John George Brown (1831–1913)

New York City, 1878

Oil on canvas

46 1/2 x 36 in.

Gift of Ralph May

1971.588

Born in England, Brown immigrated to Brooklyn, New York, in 1853. Having achieved enormous success painting city life, he became interested in the arduous lives of North Atlantic fishermen. Brown spent the summer of 1877 at Grand Manan Island, off northeastern Maine, and returned the following year, also visiting Gloucester, Massachusetts. Here, a hollow-eyed fisherman holds his dory’s rudder while smoking a pipe. Despite the threatening clouds, he appears unconcerned by his livelihood’s risks. Winslow Homer (1836-1910) addressed a similar theme seven years later in his painting, The Fog Warning, painted in 1885, now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.