Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

At Home in New England

Gallery Two

The word “home” has complex meanings, which are expressed in different ways in this gallery. Most familiar is the building we call home, with spaces designated for sleeping, cooking, and working or relaxing. Establishing a home is a creative act—the choices we make in designing, furnishing, and maintaining it reflect who we are and how we want others to see us. At one end of that idea is the grand room created by Henry Davis Sleeper, who built what is now Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House in Gloucester, Massachusetts. At the other end is the anonymous woman baking in an antiquated—yet atmospheric—kitchen.

More abstract is the place we call home—be it a town, farm, or suburban development. New England has many places that are multilayered: new buildings coexist with much older ones, and natural and economic factors continually reshape the landscape.

For a closer look at the paintings in this gallery, click on the images below and use the zoom feature. Some of the paintings have even more information, including historical photographs, additional context, and a glimpse into the work of the conservation lab. (If the images or text seem too small or large in your browser, try clicking ctrl and + or – key to adjust.)

Gallery 1: Land and Sea Gallery 2: At Home Gallery 3: New England’s People Gallery 4: The Wide World

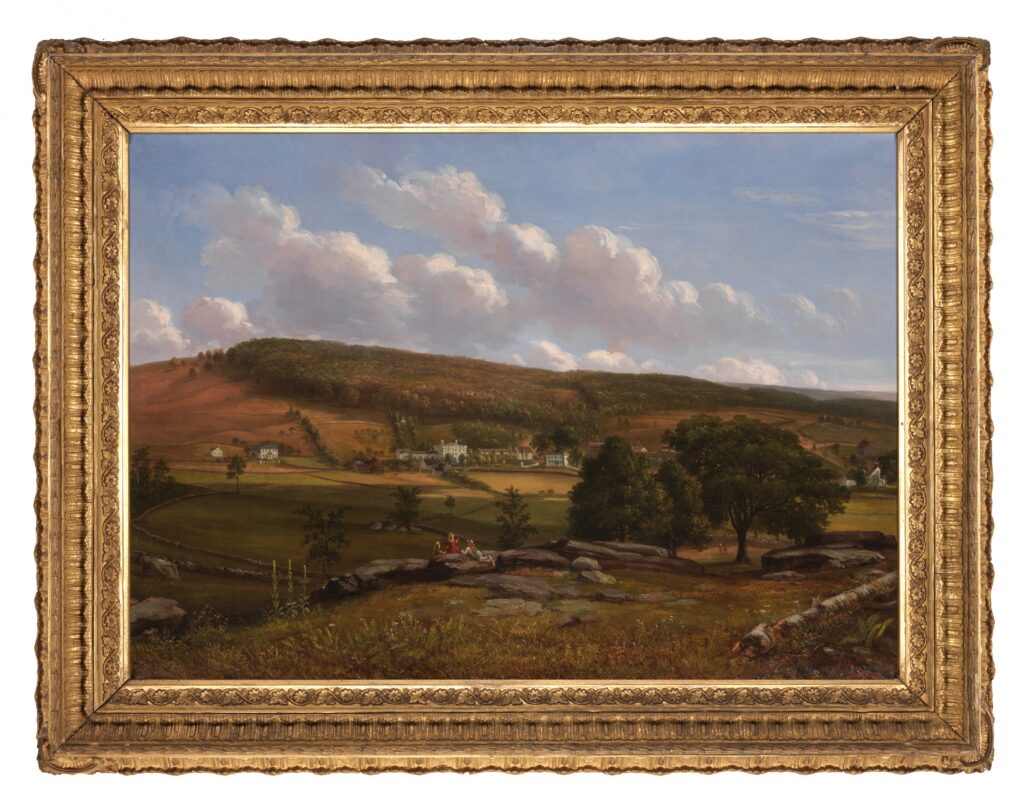

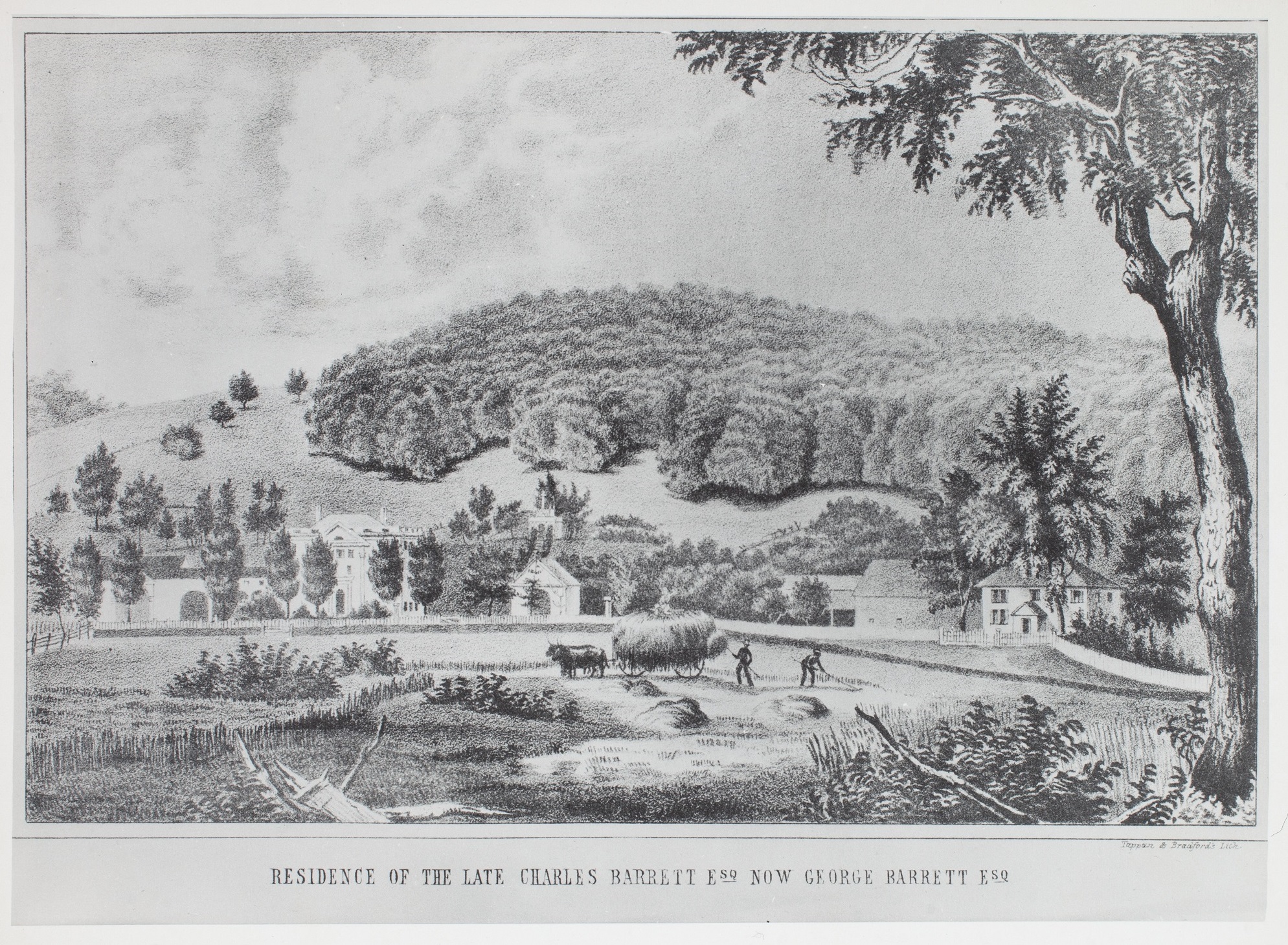

Forest Hall

Benjamin Champney (1817–1907)

New Ipswich, New Hampshire, c. 1850

Oil on canvas

30 1/2 39 ¼ in.

Gift of Caroline Krause

2019.29.1ab

When Benjamin Champney returned to his hometown of New Ipswich, New Hampshire, in 1849 after nearly a decade training in Europe, the scenes he drew were not of the industries that thrived nearby. Rather, he depicted a peaceful agrarian landscape which he surely kept in his mind’s eye while living in Paris. Frederic Kidder and Augustus Gould used several of Champney’s drawings as illustrations in their History of New Ipswich, published in 1852. Champney also turned some of the drawings into large-scale paintings like this one showing Forest Hall, now Historic New England’s Barrett House, nestled into the hillside.

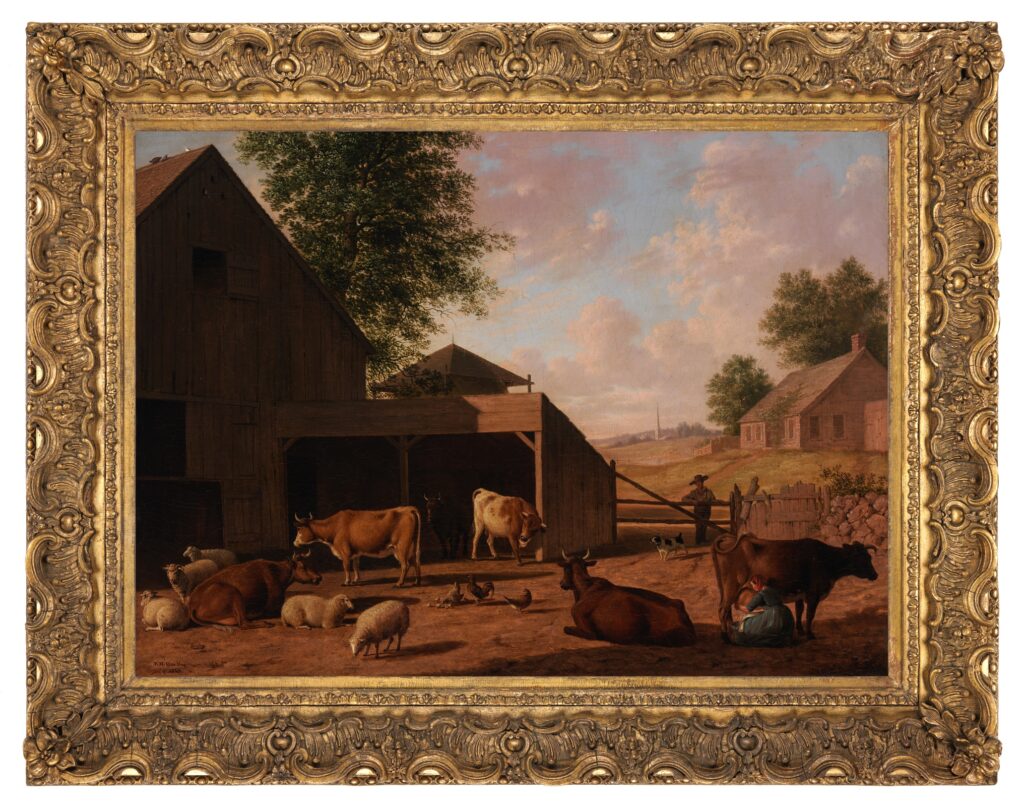

Barnyard Scene, Sunset

Thomas Hewes Hinckley (1813–1896)

Dorchester, Massachusetts, 1848

Oil on canvas

30 5/8 x 39 in.

Bequest of Dorothy S. F. M. Codman

1969.773

When this was painted in 1848 the divisions that would ripen into the Civil War were smoldering in New England. Already violence had broken out between those who supported the status quo and those who fought for abolition. This painting can be seen as an antidote, an intentionally sanitized view of an agrarian world. There is no hint of the cow and sheep dung, or the flies, or the dirt that would surely be visible on the white apron of the maid a-milking. And no hint of the storm clouds we now know were on the horizon.

Portsmouth Street Scene

William H. Titcomb (1824–1888)

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1854

Oil on canvas

28 x 35 7/8 in.

Gift of Ralph May

1971.657

Because early religious leaders required that families reside near the meeting house, New England towns developed as a series of closely settled communities. Later, densely spaced older buildings at the core of many of these towns were surrounded by an outer ring of larger lots and wider streets like the ones depicted here. Today, this peaceful townscape is a busy intersection with a traffic light in downtown Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

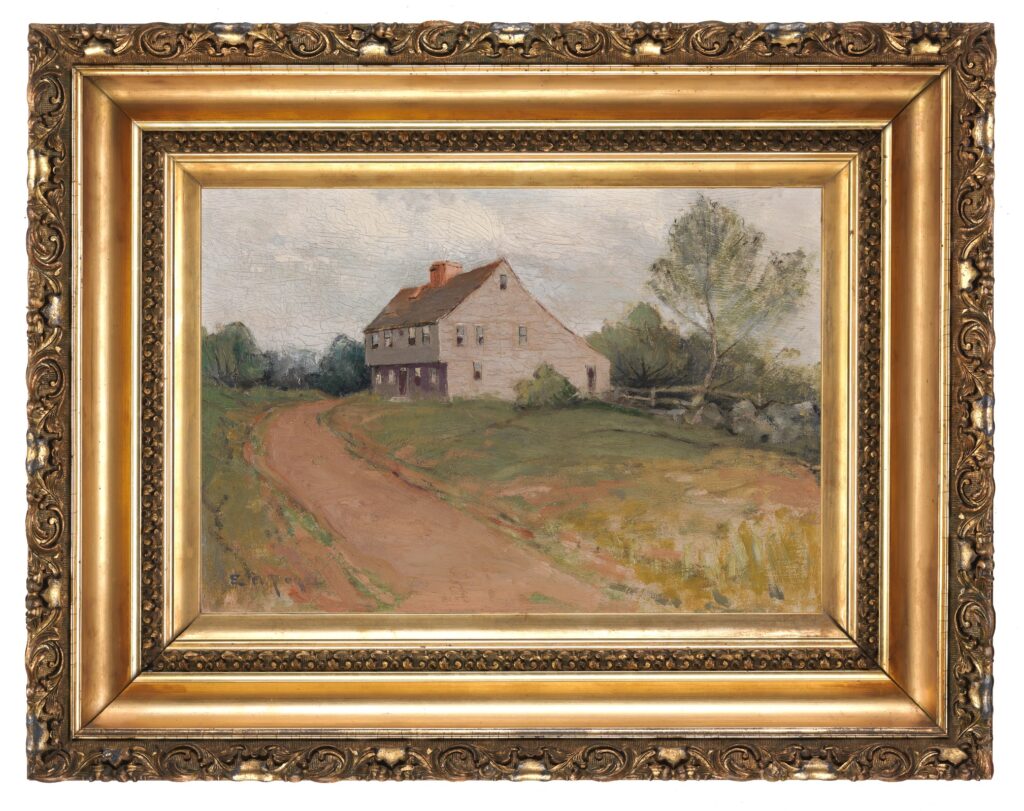

Boardman House

Edward Page (1850–1928)

Saugus, Massachusetts, 1899

Oil on canvas

14 5/8 x 18 5/8 in.

Museum purchase

2010.16.1

In the early years of the twentieth century, many New Englanders were drawn to old things, whether architecture or artifacts, as tangible pieces of the past during a time of economic upheaval and mass immigration. Boardman House, a great historical relic built in 1692 in Saugus, Massachusetts, remained in the Boardman family until 1911. By that time the original 300 acres surrounding the house had been reduced to four. When the house was threatened with development in 1914, Historic New England founder William Sumner Appleton (1874–1947) purchased it. It remains one of the organization’s most significant early properties.

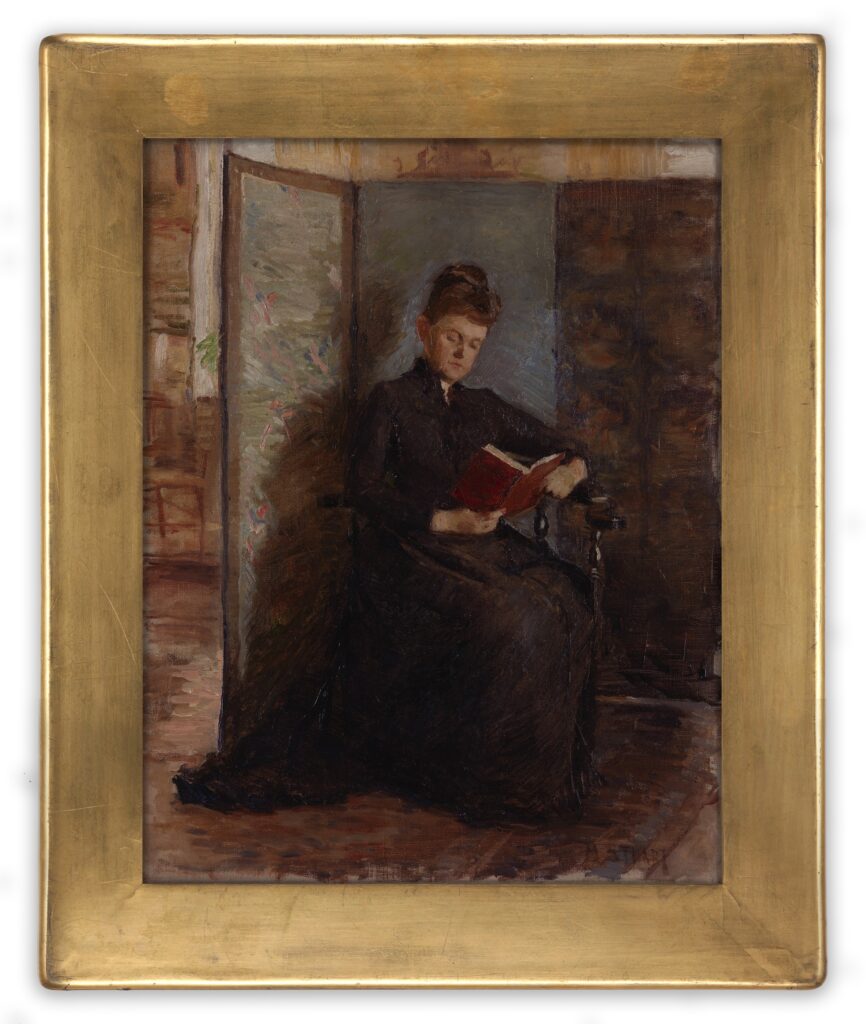

Mary Elizabeth Cutting Buckingham (1851–1896)

Mabel Stuart (1867–1939)

Wayland, Massachusetts, 1890–96

Oil on canvas

22 ½ x 18 ½ in.

Gift of Edwin Buckingham Sears

1987.1460

Portraits of women reading are a familiar device in the history of art, often used to suggest the figure’s erudition and independence. In this example, whether it was the sitter’s choice or the artist’s, the depiction of Mary Buckingham reading appropriately reflected her interests and education. Stuart may have gotten the commission for the painting through her partner, vaudeville actress Beatrice Herford. Herford and Buckingham both lived in Wayland, Massachusetts.

Roundabout Chair

Probably Massachusetts, 1730–40

Maple, pine

42 x. 22 x 19 in.

Gift of Edwin Buckingham Sears

1987.1444

This is the chair in which Mary Buckingham sits in the portrait above. According to her grandson, she purchased it during an antiquing trip to Salem, Massachusetts, in the 1890s. In the eighteenth century, these chairs were often used at desks and were called “roundabout” chairs.

Woman Working in a Kitchen

Unknown artist

Northeastern United States, 1880–1900

Oil on board

20 ¼ x 24 5/8 in.

Gift of the Joan Pearson Watkins Trust

2016.64.2

While images of men working are celebrated in art history circles, in American paintings women are more often recorded at leisure. Here a woman stands before a window leaning over a table kneading dough. The curvature of her spine and her strong arms reflect years of hard work. Her kitchen, a room celebrated today as “the heart of the home,” is clearly a work space more than a place to gather.

Henry Davis Sleeper (1878–1934)

Wallace Bryant (1870–1953)

Boston, 1906

Oil on canvas

60 3/8 x 66 1/4 in.

Gift of Steven Sleeper, the sitter’s brother

1941.1703

Henry Sleeper is seen here in his late twenties, around the time he made his first visit to Gloucester, Massachusetts. The following year Sleeper purchased land there and started building the “cottage” that won him acclaim as an interior decorator, now known as Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann house, an Historic New England property. Bryant painted Sleeper at his widowed mother’s Boston house, where he still lived. Seated in a throne-like armchair with his legs crossed, Sleeper is surrounded by books and artworks that reflect his aesthetic sensibility. Highly attuned to color, Sleeper matched his tie perfectly with the oxblood vase to his right.

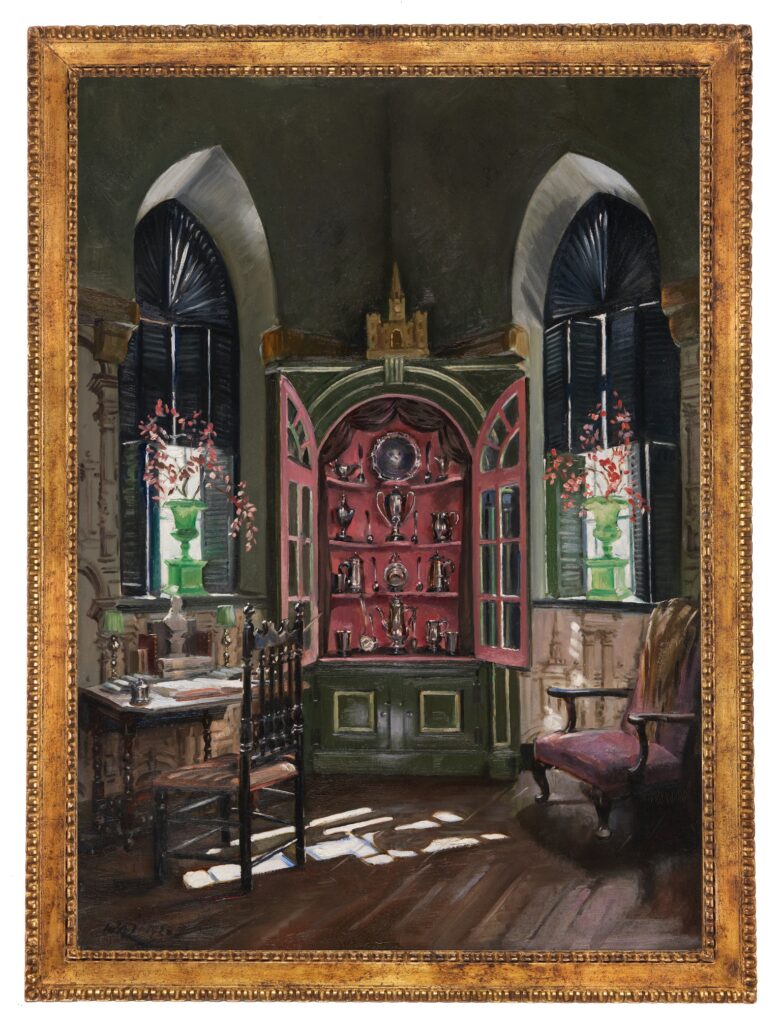

The Chapel Chamber at Beauport

William Bruce Ellis Ranken (1881–1941)

Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1928

Oil on paper

34 3/8 x 25 ½ in.

Gift of Constance McCann Betts, Helena Woolworth Guest, and Frasier W. McCann

1942.4634

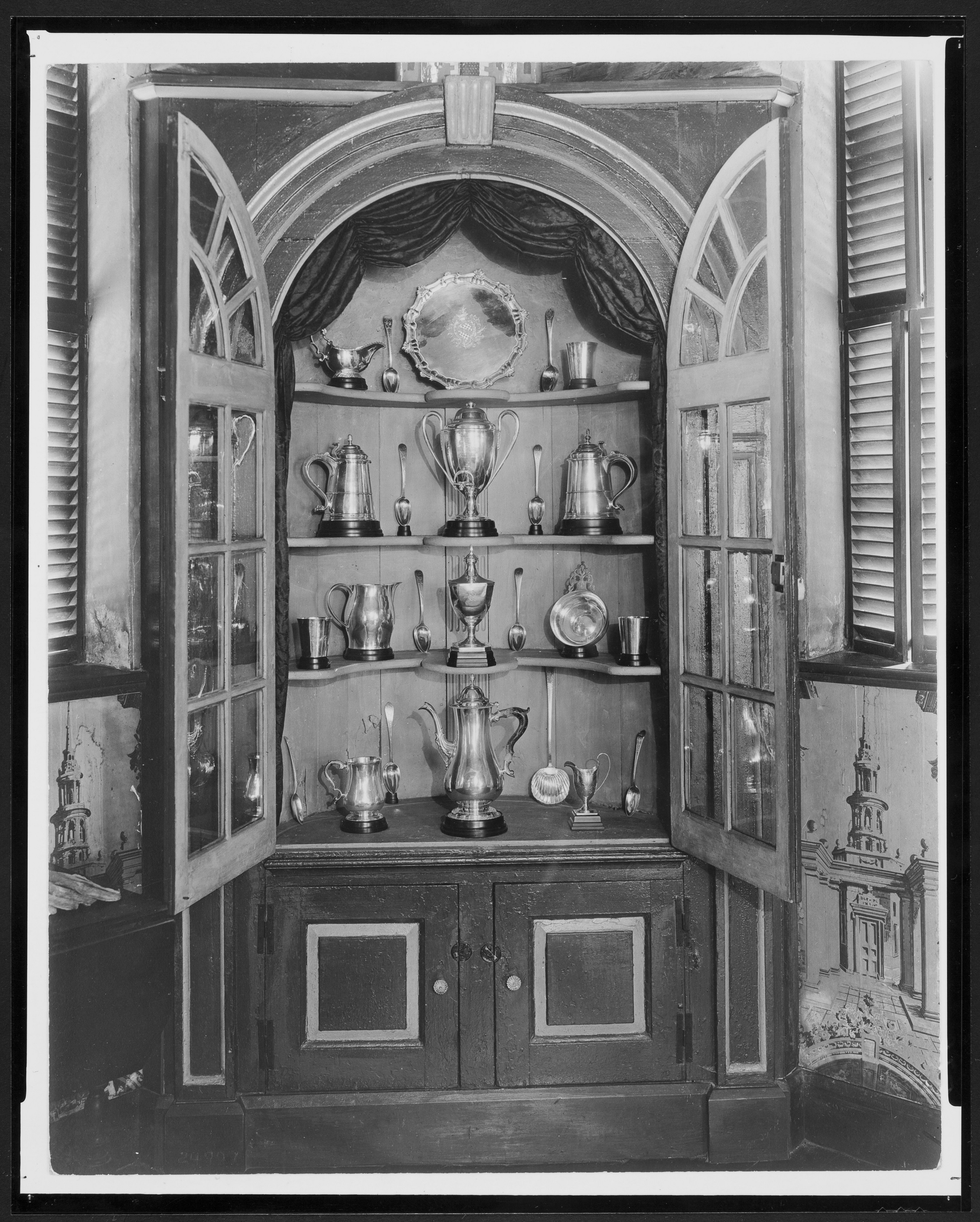

When Country Life magazine invited Sleeper to illustrate a dozen of his rooms, he arranged to have them painted by William Ranken, a portraitist introduced to Boston society by John Singer Sargent. Ranken’s view of the Chapel Chamber focuses on the important collection of silver by Paul Revere which Sleeper donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Sleeper’s eclectically furnished room is a masterclass in color orchestrations and contrasts of light and shadow. Note the brushstrokes that suggest sunlight on the floor, and how Ranken toned down the vivid wallpaper to retain focus on the cabinet.

Urn and Stand

Possibly Boston & Sandwich Glass Company

Sandwich or Boston, Massachusetts, or Northeastern United States, 1850–60

Uranium glass

25 ¼ x 10 ½ x 10 ½ in.

Gift of Constance McCann Betts, Helena Woolworth Guest, and Frasier W. McCann

1942.2858.2AB

Throughout Beauport, Henry Sleeper displayed comparatively inexpensive pieces of colored glass to dramatic effect. This green glass urn is one of a set; two smaller versions appear in Ranken’s portrait of the Chapel Chamber, where the shutters have been opened just enough to allow the glass to glow without taking too much attention away from the room’s other charms.

A Country Home

Frank Henry Shapleigh (1842–1906)

Arlington, Massachusetts, 1866

Oil on canvas

27 9/16 x 39 ½ in.

Bequest of Amelia Peabody

1985.662

Soon after cofounding the banking firm Kidder, Peabody, & Co. in 1865, Francis Peabody moved from Boston with his family, including daughters Fannie and Lillian, seen in the foreground, to this tranquil location in Arlington, Massachusetts. The cottage at the end of the drive, built in 1843, is a distinguished example of the Gothic Revival style widely promoted in Andrew Jackson Downing’s influential book, Cottage Residences (1842). This painting was made early in Frank Shapleigh’s career, not long after his discharge from the Union Army. Later he traveled to Europe to hone his skills.

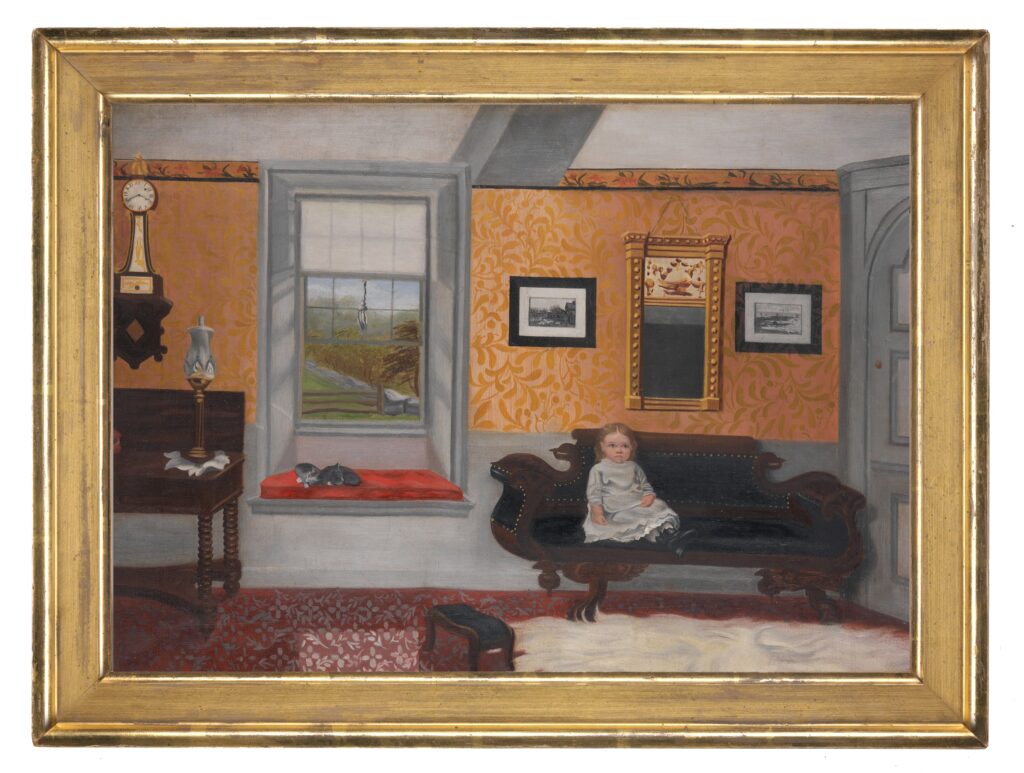

The Cushing Parlor

Ella Emory (dates unknown)

Hingham, Massachusetts, 1878

Oil on canvas

15 X 20 in.

Museum purchase with funds provided by an anonymous gift

1994.21

For some New Englanders home was the place their parents, grandparents, and many generations before them had lived. In 1878 Ella Emory, her sister, and her niece, Alice Cushing, spent the summer at their family’s seventeenth-century ancestral home in Hingham, Massachusetts. During the visit Emory painted this view of the west parlor with Alice seated on a sofa, two kittens curled up nearby, and a mishmash of furnishings accumulated over the decades.

Itinerant Artist Scene

Unknown artist

Northeastern United States, c. 1845

Colored pencil and water-based media on paper

15 1/8 x 18 ¾ in.

Museum purchase

2019.5.1

Oliver Wendell Holmes described itinerant artists as “wandering Thugs of Art whose murderous doings with the brush used frequently to involve whole families; who passed from one country tavern to another, eating and painting their way.” He despised the work that still “too frequently” ornamented the walls of taverns and homes. But in the days before photography was widely available, traveling artists offered an affordable and accessible alternative to their academy-trained colleagues. This charming scene full of comical detail shows a family gathered in their kitchen while just such a “thug” begins to paint the eldest son.