Eustis Estate

Eustis Estate

Defying Barriers

The paintings in Artful Stories depict or were made by a wide array of people. Some of these individuals faced significant challenges in life because of discrimination against their race, gender, sexual orientation, class, or other attribute. Art’s capacity to “put a face” on problematic aspects of the past is both powerful and deeply humanizing.

Woman Reading Under a Tree

Edward Mitchell Bannister (c. 1828–1901)

Probably Rhode Island, 1880–85

Oil on canvas

14 3/8 x 18 3/8 in.

Museum purchase

2018.35.1

Born in Canada, Edward Mitchell Bannister was one of the few black artists to be widely recognized in the United States before 1900. Arriving to accept a prize at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, he was refused entry, but finally received the medal after fellow exhibitors protested. Bannister taught at the Rhode Island School of Design and painted local scenery using techniques of the French Barbizon School, which prioritized nature’s ordinary beauties over iconic views such as Benjamin Champney’s Mount Chocorua. Here, a woman reads while breezes flutter the leaves and grasses.

Henry Davis Sleeper (1878–1934)

Wallace Bryant (1870–1953)

Boston, 1906

Oil on canvas

60 3/8 x 66 1/4 in.

Gift of Steven Sleeper, the sitter’s brother

1941.1703

Henry Sleeper is seen here in his late twenties, around the time he made his first visit to Gloucester, Massachusetts. The following year Sleeper purchased land there and started building the “cottage” that won him acclaim as an interior decorator, now known as Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann house, an Historic New England property. Bryant painted Sleeper at his widowed mother’s Boston house, where he still lived. Seated in a throne-like armchair with his legs crossed, Sleeper is surrounded by books and artworks that reflect his aesthetic sensibility. Highly attuned to color, Sleeper matched his tie perfectly with the oxblood vase to his right.

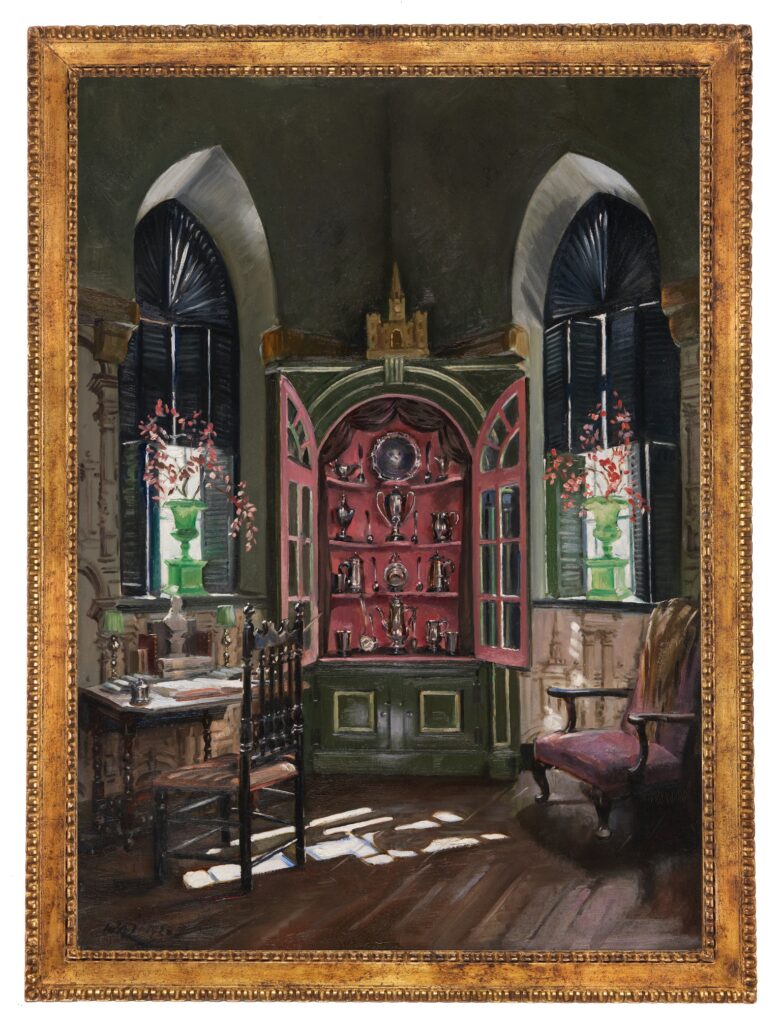

The Chapel Chamber at Beauport

William Bruce Ellis Ranken (1881–1941)

Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1928

Oil on paper

34 3/8 x 25 ½ in.

Gift of Constance McCann Betts, Helena Woolworth Guest, and Frasier W. McCann

1942.4634

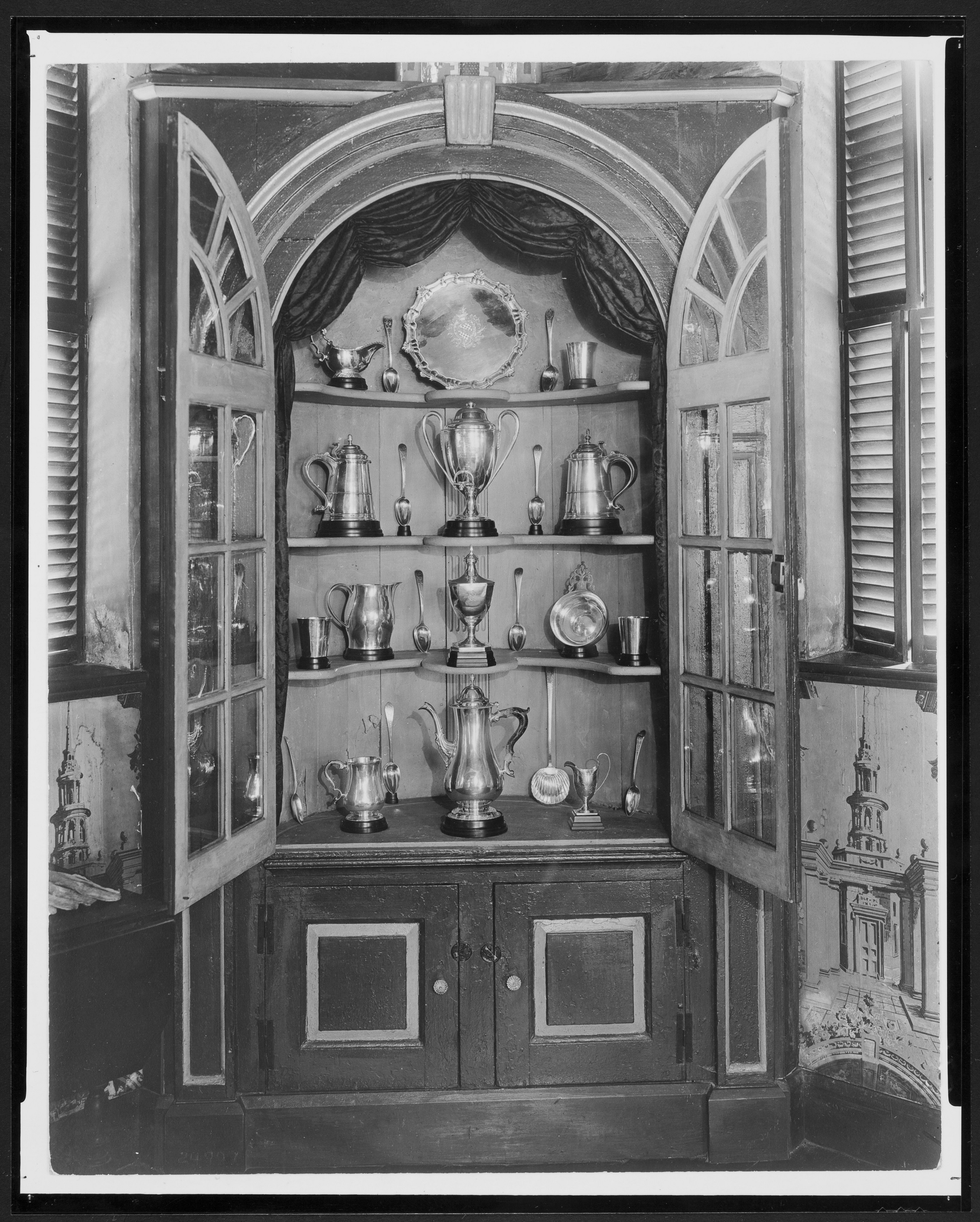

When Country Life magazine invited Sleeper to illustrate a dozen of his rooms, he arranged to have them painted by William Ranken, a portraitist introduced to Boston society by John Singer Sargent. Ranken’s view of the Chapel Chamber focuses on the important collection of silver by Paul Revere which Sleeper donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Sleeper’s eclectically furnished room is a masterclass in color orchestrations and contrasts of light and shadow. Note the brushstrokes that suggest sunlight on the floor, and how Ranken toned down the vivid wallpaper to retain focus on the cabinet.

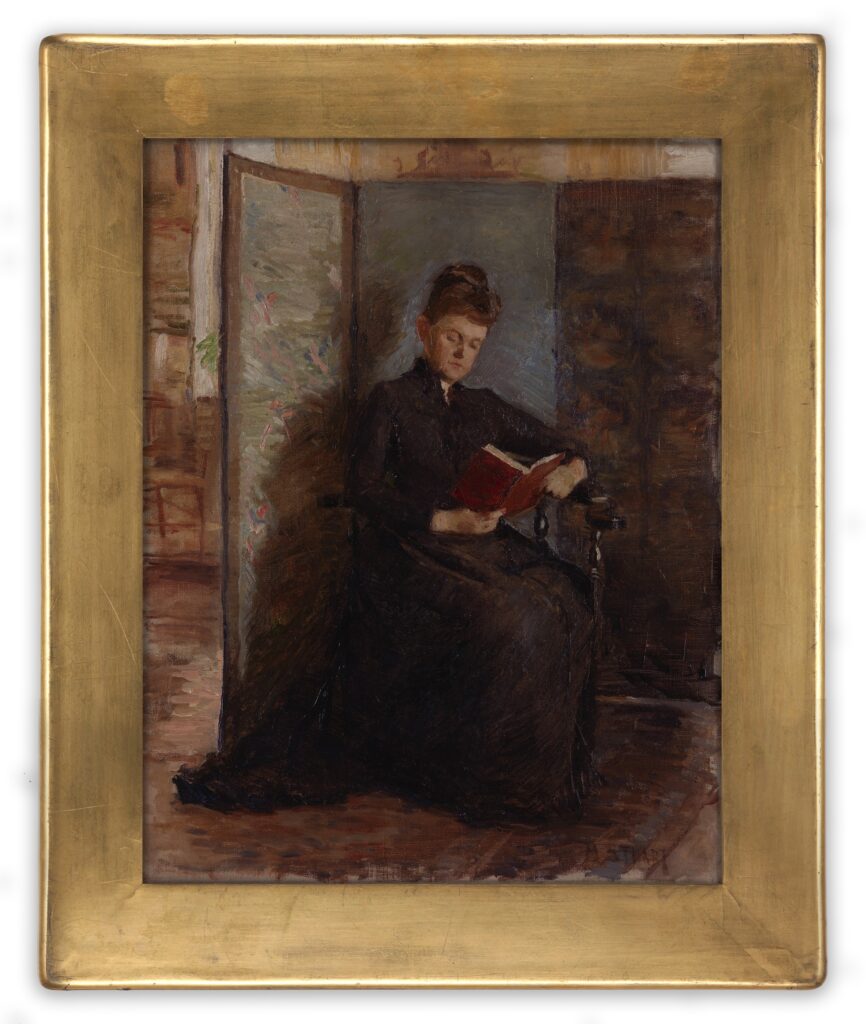

Mary Elizabeth Cutting Buckingham (1851–1896)

Mabel Stuart (1867–1939)

Wayland, Massachusetts, 1890–96

Oil on canvas

22 ½ x 18 ½ in.

Gift of Edwin Buckingham Sears

1987.1460

Portraits of women reading are a familiar device in the history of art, often used to suggest the figure’s erudition and independence. In this example, whether it was the sitter’s choice or the artist’s, the depiction of Mary Buckingham reading appropriately reflected her interests and education. Stuart may have gotten the commission for the painting through her partner, vaudeville actress Beatrice Herford. Herford and Buckingham both lived in Wayland, Massachusetts.

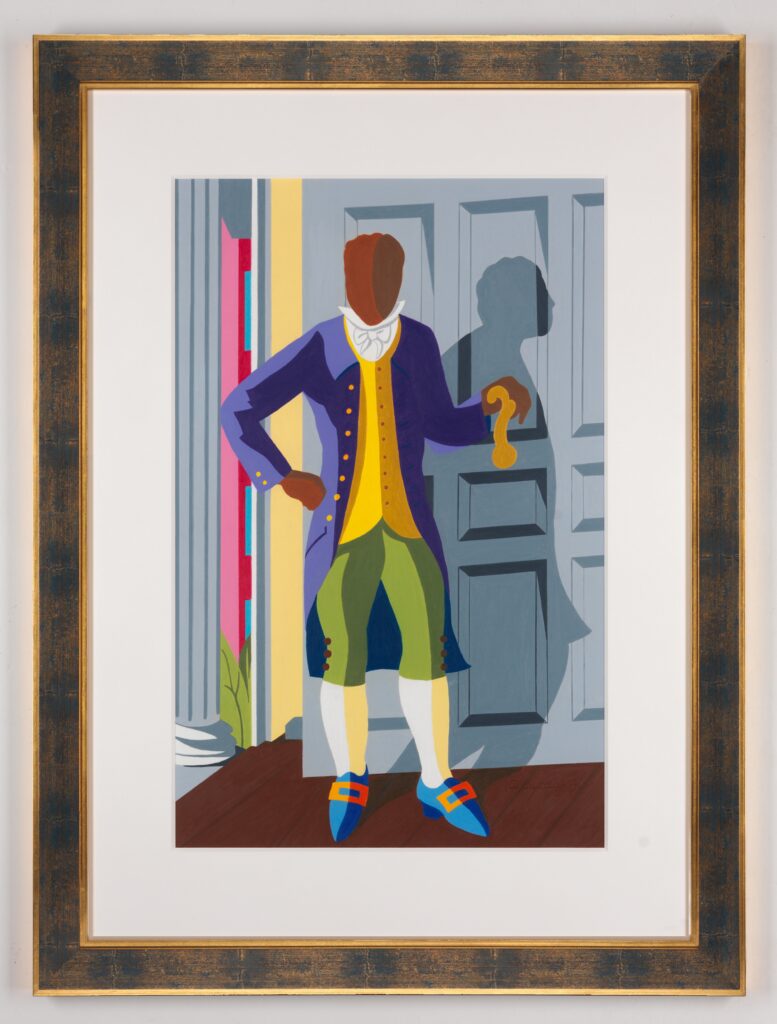

Cyrus Bruce (dates unknown)

Richard Haynes Jr. (b. 1949)

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 2018

Oil and wax-based crayons on paper

39 ¼ x 29 in.

Gift of the artist

2019.22.1

In 1783, Cyrus Bruce, a formerly enslaved black man, began working for Governor John Langdon in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where he was admired for his “gentlemanly appearance.” Few people in Bruce’s situation were recorded for posterity, so in 2018, when Haynes, an African American artist from Portsmouth, undertook a residency at Historic New England’s Langdon House, he had to imagine the servant’s appearance. This pose suggests Bruce’s authority, and his shadow seems to move forward toward new opportunities. Yet the door knocker resembles a question mark, leading us to wonder about Bruce’s fate. You can see Richard Haynes at work on this portrait in 2018 in the photo at left.

Clementina Beach (1774–1855)

Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828)

Boston, 1820–25

Oil on canvas

35 ½ x 30 ¾ in.

Museum purchase

2012.39.1

In the early years of the nineteenth century when there were few opportunities for genteel women to earn a living, Clementina Beach and Judith Saunders ran one of New England’s elite schools for girls, located in Dorchester, Massachusetts. We do not know whether grateful students commissioned this portrait or Beach commissioned it herself. In either case it is an unusually early portrait of a woman who was painted not because of who her family was but for what she herself had achieved.

Portrait of a Mi’kmaw

Isaac Sprague (1811–1895)

Possibly New Hampshire, 1845–50

Watercolor on paper

15 ¾ x 12 ¾ in.

Museum purchase

2011.117.1

In the mid-nineteenth century when this watercolor was painted, the Mi’kmaq people (Mi’kmaw in the singular) continued to occupy areas of northern New England and southern Canada where they had lived for centuries. They still live in those areas today. Unlike many artists who painted romanticized views of Native Americans, Isaac Sprague, a protégé of the great naturalist John James Audubon, accurately recorded the details of this Mi’kmaw man’s clothing and environment.

Copy of the Self-portrait of Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)

Elizabeth Adams (1825–1898)

Florence, 1865–74

Oil on canvas

52 ½ x 46 in.

Gift of the artist’s nephew, Boylston Adams Beal

1937.287

According to her biographer, Elizabeth Adams “dared to believe that a woman might dedicate her life to a profession.” Born to a renowned Boston family, Adams headed to France and Italy when she was thirty-four and spent more than a decade there devoted to the study of art.

This is Adams’s copy of the self-portrait of the French court artist Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun painting Queen Marie Antoinette. As one of the few women ever invited to contribute to the collection of artists’ self-portraits at Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, Le Brun’s life story surely appealed to Adams, whose own artistic ambition was realized in 1885 when one of her paintings was chosen for exhibition at the Paris Salon.

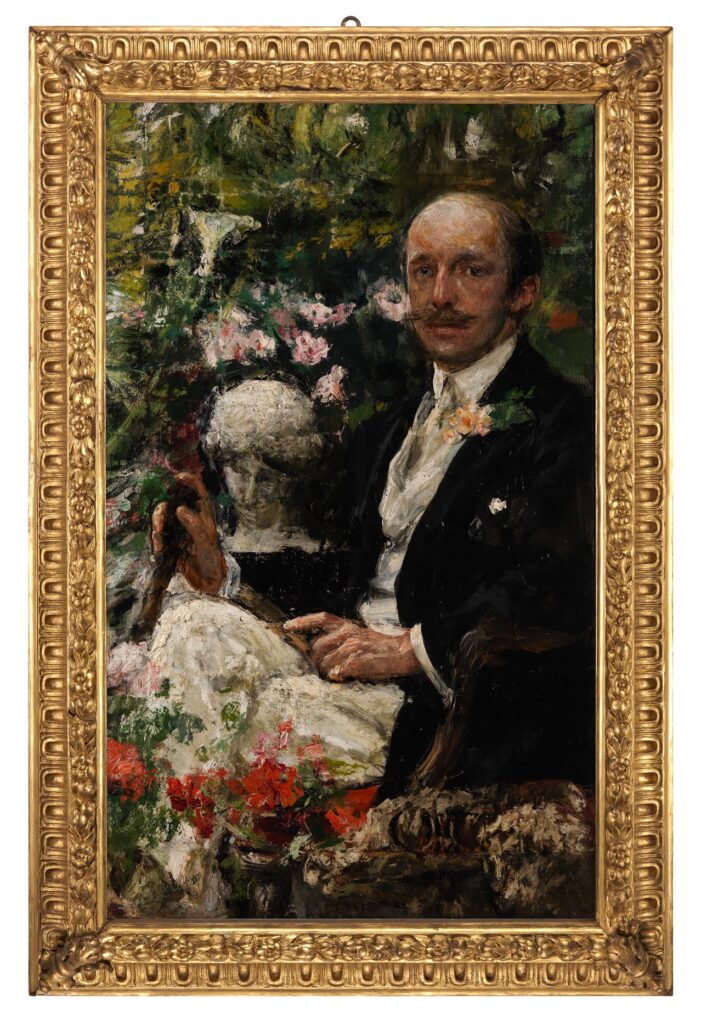

Richard Norton (1872–1918)

Antonio Mancini (1852–1930)

Rome, c. 1905

Oil on canvas

47 1/8 x 31 ½ in.

Bequest of Susan Norton, the sitter’s daughter

1990.104

As a son of Harvard University professor Charles Eliot Norton, Richard Norton was destined to be cosmopolitan. He was the director of the American School of Classical Studies at Rome when he commissioned this portrait. Mancini was a daring choice: the Italian artist suffered from mental illness but was championed by John Singer Sargent, who introduced him to American patrons like Isabella Stewart Gardner.

Mancini’s colorful scratchings on Norton’s face are bold; even less conventional are the exuberant brushstrokes of lush foliage. In the photograph above, you can see his unique grid method of painting.

Landscape at Cortina

Sarah Wyman Whitman (1842–1904)

Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy, 1877–90

Oil on board

16 ½ x 20 ¼ in.

Gift of Julia Richardson

1966.399

This painting has long graced the South Berwick, Maine, bedroom of writer Sarah Orne Jewett (1849–1909) at Historic New England’s Jewett House. Among Jewett’s large circule of femail friends was Sarah Wyman Whitman, who painted this scene in Italy’s Dolomite Mountains. The abandoned plough on which the painting is focused may have appealed to Jewett, whose writing celebrated the earnest labor of Maine farmers.

Whitman studied with leading painters and eventually became one of the country’s most influential book designers. She was the lead designer for the Boston publisher Houghton Mifflin Company and designed virtually all the covers of Jewett’s books.